Healthcare perspectives from The Economist Intelligence Unit

Around a quarter of heart attack or stroke patients in Asia-Pacific are re-hospitalised with a follow-on event, according to The Economist Intelligence Unit

Related content

The cost of inaction: Secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in Asi...

The burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) across Asia-Pacific varies by country, but is nonetheless substantial. Collectively CVD is the leading or second-leading cause of death across the region and the prevalence continues to rise. Further, shifting demographics in the region—with both an increase in younger people experiencing CVD and ageing populations with multiple comorbidities—are putting health systems under increasing pressure.

Progress in tackling the problems associated with CVD has focussed in the primary prevention space, and age-standardised incidence of CVDs are beginning to fall. However, undermining this progress, there is still an unacceptably high recurrence rate of heart attack and stroke with associated economic and human cost. As more patients now survive an initial heart attack or stroke, the secondary event burden is likely to increase. This demands urgent attention but also represents an eminently realisable opportunity to improve care and outcomes in this group.

This analysis by the Economist Intelligence Unit explores the policy response to managing secondary cardiovascular events in eight Asia-Pacific economies: Australia, mainland China, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

Key findings of the research include:

While CVD policies do exist, some are more comprehensive than others. The success of translating policy on modifiable risk factors into legislation and action, along with measuring impact, is yet to be defined. Government audits are lacking. Primary care systems, a key component for integrated care, are evolving. Rehabilitation services exist but coverage is limited, and they struggle to recruit and retain patients. Integrated, coordinated patient-centred care is a necessary goal. Patient empowerment is essential for success. Maximising data and measuring progress.

Other language versions:

Simplified Chinese | Japanese | Korean

Infographic:

English | Simplified Chinese | Japanese | Korean

The Cost of Silence: Cardiovascular disease in Asia

The Cost of Silence: Cardiovascular disease in Asia is a report by The Economist Intelligence Unit and EIU Healthcare. It provides a study of the economic impact of CVD risk factors on the following Asian markets: China, Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

Specifically, the study captures the cost of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke. IHD, also called coronary heart disease (CHD) or coronary artery disease, is the term given to heart problems caused by narrowed heart (coronary) arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle, which can lead to stable angina, unstable angina, myocardial infarctions or heart attacks, and sudden cardiac death. Stroke is characterised by the sudden loss of blood circulation to an area of the brain due to blockage of brain vessels, or a haemorrhage or blood clot.

This study further combines an evidence review of existing research on CVDs and primary research in the form of expert interviews.

Key findings of the report are as follow:

The rising incidence of CVD poses a substantial challenge to Asia-Pacific markets The four main modifiable cardiovascular risk factors pose a communications challenge for governments and health agencies. Hypertension is the risk factor that contributes the highest cost. The costs of CVDs are not fixed. Greater awareness and policymaker attention can substantially reduce CVD costs as many obstacles and corresponding solutions have been identified as effective. Policy options for primary prevention include choice “nudges”. Effective secondary prevention can also significantly affect costs and outcomes.Related content

조치 부재의 비용: 아시아 태평양 지역 내 심혈관 질환의 2차 예방

아시아 태평양 지역의 심혈관 질환(CVD)부담은 국가별로 상이하나 모두 상당하다.CVD는 지역 전반에서 사망 원인 1위 또는2위를 차지하고 있으며, 유병률도 계속높아지고 있다. 또한 CVD를 경험하는 젊은환자와 여러 동반 이환을 가진 고령화 인구두 집단 모두의 증가라는 지역 내 인구통계적변화로 인해 각국의 보건의료체계에 부하가걸리고 있다.

CVD 관련 문제 해결에 관한 진척은 1차예방 분야에 초점이 맞춰져 이루어져왔으며, CVD의 연령표준화 발생률은감소하기 시작했다. 그러나 여전히 허용할수 없는 높은 수준의 심장마비 및 뇌졸중재발률과 그에 따른 경제적 및 인적 비용이존재해 이러한 진척을 저해하고 있다. 첫심장마비 또는 뇌졸중 생존자가 더많아짐에 따라 2차 사건 관련 부담이증가할 가능성이 높다. 이는 긴급한 주의를요구하는 상황인 동시에, 해당 환자 집단의관리와 결과를 개선할 수 있는 탁월하고현실적인 기회이기도 하다.

본 이코노미스트 인텔리전스 유닛분석에서는 아시아 태평양 지역8개국(호주, 중국, 홍콩, 일본, 싱가포르,한국, 대만, 태국)의 2차 심혈관 사건관리에 대한 정책적 대응을 살펴본다. 본 연구의 주요 결과는 다음을 포함한다. 관련 정책은 확실히 존재하나, 정책이상당히 포괄적인 국가도 있고 그렇지 않은국가도 있다. 조절 가능한 위험인자에 대한 정책을 법률과실천에 성공적으로 반영했는지 여부와 그로인한 영향은 아직 확인되지 않았다. 정부 감사가 결여되어 있다. 통합 관리의 핵심 요소인 1차 의료 체계가발전하고 있다. 재활 서비스가 존재하나 보장 범위가제한적이며, 업체들은 환자 유치와 유지에어려움을 겪고 있다. 필요한 목표는 환자 중심의 통합적이고조정된 관리 환자 권한부여는 성공의 핵심 데이터 극대화 및 진척도 측정

高まる二次予防の重要性: アジアにおける心疾患医療の現状・課題

国によって状況は異なるものの、心血管疾患(CVD)がもたらす負担が非常に大きいことは間違いない。CVD は全てのアジア諸国で二大死因となっており、患者数も増加の一途を辿っている。またアジアでは、若年層のCVD 患者・高齢者層の合併症患者が並行して増えており、医療体制にさらなる負担をもたらしている。

近年、CVD に関連する問題への対策は、一次予防の分野で進化を遂げつつあり、年齢調整罹患率にも減少の兆しが見られる。しかし急性心筋梗塞・脳卒中の再発率は依然として高く、その経済的・人的コストも大きいのが実状である。また一度目の発症での生存率が向上している今、再発によって生じる負担はさらに増す可能性が高い。ただし、対応が急務となっているこうした現状に取り組むことが現実的であることを鑑みると、当該患者グループのケア体制・アウトカムを向上させる重要な機会だと捉えることができる。

ザ・エコノミスト・インテリジェンス・ユニット(EIU)の本報告書は、アジア太平洋地域8 カ国(オーストラリア・中国・香港・日本・シンガポール・韓国・台湾・タイ)を対象として、CVD の再発予防に向けた政策的取り組みを検証する。

主要な論点は以下の通り:

多くの国はCVD 政策を掲げているが、包括性の面で大きな差がある。 改善可能なリスク因子への取り組みは、具体的な法案・行動計画、および成果評価に必ずしも結びついていない。 政府による成果評価の仕組みは発展途上である。 包括医療に不可欠なプライマリケアは近年進化を遂げつつある。 多くの国はリハビリサービスを実施しているが、提供能力は限られており、利用者も伸び悩んでいる。 連携を通じた患者中心の包括医療の必要性 取り組みの成功の鍵を握るのは患者エンパワーメント データ活用の加速と成果評価の仕組みも重要な鍵となる

Data and digital technologies to improve clinical outcomes for high-risk ca...

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) account for around one quarter of deaths in Australia.1 The Economist Intelligence Unit estimates that the annual direct and indirect costs of CVD in Australia totals US$12.3bn.2 There are numerous modifiable risk factors for CVD, but the most important include hypertension (high blood pressure), high cholesterol, tobacco use, diabetes and obesity.3 While much of the recent focus has been on primary prevention through lifestyle modification, those highrisk patients with existing CVD—such as peripheral artery disease or a previous heart attack or stroke—require particular attention to avoid further morbidity and mortality.

The improved use of data and digital health tools has the potential to enable more coordinated and patient-centred models of care. The Digital Health CRC takes this further in saying “research and innovation in digital health offers Australia significant economic and business development opportunities, as well as great promise for the better health of our community”.4

On 27 May 2020, The Economist Intelligence Unit—supported by the Australian Cardiovascular Alliance (ACvA) and Digital Health CRC and with sponsorship from Amgen—convened a virtual roundtable discussion with 25 representatives from across the Australian cardiovascular healthcare landscape.

Co-hosted by the Economist Intelligence Unit with Dr Gemma Figtree, president of ACvA and professor in medicine at University of Sydney & Royal North Shore Hospital, and Dr Tim Shaw, director of research and workforce capacity at Digital Health CRC, the roundtable aimed to identify barriers, challenges and opportunities to improve outcomes for highrisk CVD patients by improving the use of data and digital technologies.

1 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cardiovascular disease. In: Welfare AIoHa, editor. Canberra 2019. 2 Economist Intelligence Unit. “The cost of silence: Cardiovascular disease in Asia”, 2019 3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Know your risk for heart diseases”. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/risk_factors.htm (Accessed Jun 2020). 4 Digital Health CRC. “About us”. Available from: https://www.digitalhealthcrc.com/about-us/ (Accesed Jun 2020).

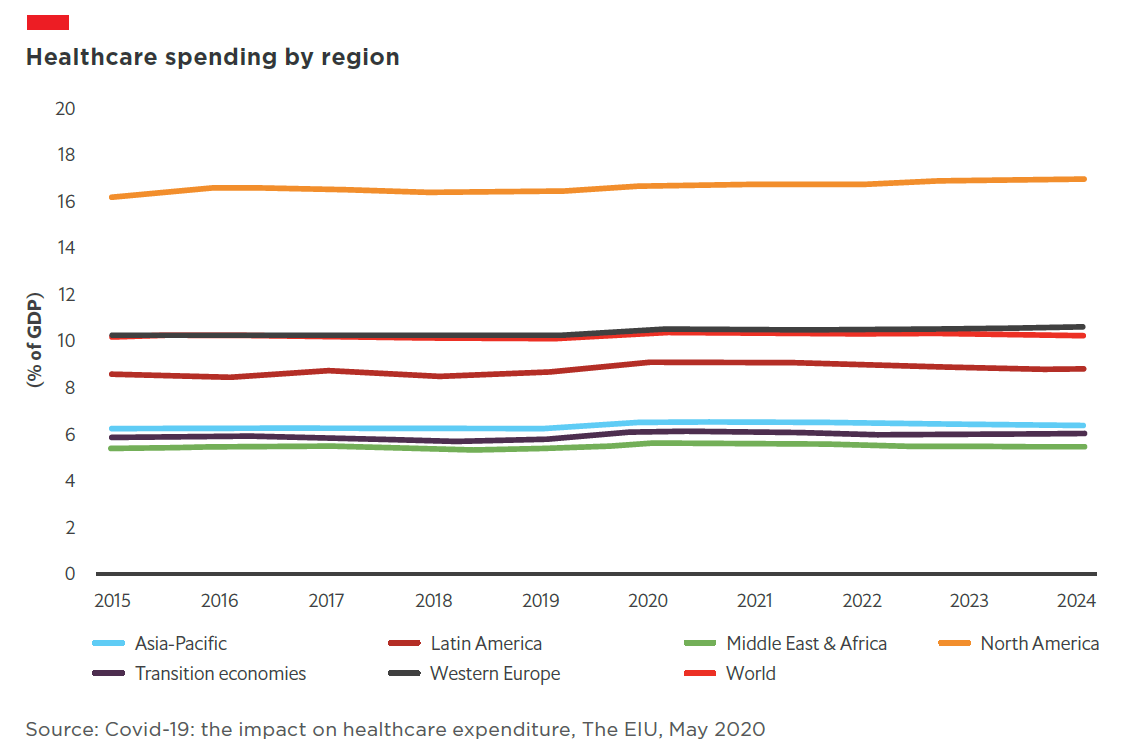

Healthcare | How will covid-19 reshape key Australian industries?

On March 11th 2020, the Australian federal government announced a A$2.4bn (US$1.6bn) funding injection into the healthcare sector to help states and territories cover the public health costs associated with treating covid-19 cases. The overall strategy was to minimise the number of people becoming sick and dying from covid-19 as well as managing the demand on Australia’s health systems.

17431

Related content

Financing sustainability: Asia Pacific embraces the ESG challenge

Financing sustainability: Asia Pacific embraces the ESG challenge is an Economist Intelligence Unit report, sponsored by Westpac. It explores the drivers of sustainable finance growth in Asia Pacific as well as the factors constraining it. The analysis is based on two parallel surveys—one of investors and one of issuers—conducted in September and October 2019.

If the countries of Asia Pacific are to limit the negative environmental effects of continued economic growth, and companies in the region are to mitigate their potential climate risks and make a positive business contribution through improving the environment and meeting the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), large volumes of investment in sustainable projects and businesses need to be mobilised. A viable sustainable finance market is taking shape in the region to channel commercial investor funds, and both investors and issuers say they are achieving a financial benefit from their investment and financing activities. The market is still in the early stages of development, however, and must expand and mature to meet investor needs.

The chief constraint on sustainable finance growth in the region has been the limited supply of bankable sustainable projects. Our research suggests supply is increasing, but with investor demand continuing to grow apace, the gap will remain an obstacle in the short- to medium-term. Among the organisations in our issuer survey, only 7% have used sustainable finance instruments to fund projects. However, nearly nine in ten (87%) said they intend to do so in the next year, which should begin to bridge the gap between supply and demand.

Based on issuers’ stated intentions, investors will have a range of instruments to choose from, including green loans and bonds and sustainability loans and bonds. Large numbers of investors indicate that they intend to deploy a greater proportion of capital to these over the next three years.

Financing sustainability | Insights video

What is driving the strong demand for financing sustainability in Asia Pacific? How can companies increase supply and start to see the benefits of sustainable finance in the next three years? We interviewed Richard Brandweiner, CEO of Pendal Australia, and Sophia Cheng, CIO of Cathay Financial Holdings and chair of Asia Investor Group on Climate Change, to find out.

To learn more: Download report | View infographic

Financing sustainability | Infographic

Financing sustainability: How do investors and issuers in APAC's sustainable finance market view the present market opportunities and constraints?

To learn more:

Download report | Watch videoDavid Miliband: International political response to covid-19 scores “D-minus”

David Miliband is taking refuge in North-west Connecticut during the covid-19 lockdown, but his thoughts are very much global, and inevitably political.

17412

Related content

Covid-19 population tracker: deaths from covid-19 and the ones we must not...

There has been a morbid fascination with the number of deaths associated with covid-19 and the extent to which countries are mishandling the crisis. But we are also facing a data crisis which distorts proper analysis of either.

Scientists are tinkering with models on the expected number of deaths based on incomplete data as not all countries apply the same covid-19 testing rules and not all deaths are accurately recorded. At the same time countries are still deliberating about who they should test, be it asymptomatic cases, only those with symptoms, those presenting to healthcare systems or healthcare workers.

Officials in the US have cast doubt on the numbers being reported by China, and not all countries have the resources to follow the WHO’s “test, test, test” advice. This is particularly true for economies with under-developed healthcare systems such as India, Africa and Latin America.

So with that cautionary note, we have tried to work with the data at hand—incomplete as it is—to map the number of confirmed cases of covid-19 against deaths per 100,000 population over time. While the absolute numbers of deaths are important to note because each loss of life is painful to loved ones, we should also look at death rates across populations to better understand the virus and to keep abreast of potentially effective containment measures. In developing countries cause of death information is often hard to obtain, mostly because systems for recording these details are inadequate or non-existent.

The bubbles represent absolute deaths in an individual country. You can eliminate regions from the timeline to see, for example, how Europe is faring against North America, or zoom in on the trajectory for an individual country. As of April 20th, death rates appear to be highest in Europe with Belgium reaching around 50 deaths per 100,000 population.

While people are still focused on covid-19 deaths, be prepared for a new type of death associated with covid-19 over time. These are deaths and morbidity that will arise as healthcare systems direct more and more resources to covid-19 and less and less to common diseases such as stroke and cancer. For developing countries, the common diseases affected will be tuberculosis, malaria and AIDS.

These “excess” deaths may also arise as people become more fearful of overloading healthcare systems or worried about catching the virus if they attend healthcare facilities including hospitals. There are also the deaths of older people living in residential care facilities or dying at home that are not being properly accounted for. If you have cancer and your treatment is delayed, that is a life and death situation for your overall prognosis. The same applies if treatment is delayed following the first signs of stroke. Patients living with chronic health conditions will see a significant change in the level of service and care received during this crisis, and the damage caused may take years to repair.

So while scientists study the data around covid-19, expect new data to emerge on how other diseases have been affected by this pandemic.

Value-based healthcare in Sweden: Reaching the next level

The need to get better value from healthcare investment has never been more important as ageing populations and increasing numbers of people with multiple chronic conditions force governments to make limited financial resources go further.

These pressures, along with a greater focus on patient-centred care, have raised the profile of VBHC, especially in European healthcare systems. Sweden, with its highly comprehensive and egalitarian healthcare system, has been a leader in implementing VBHC from the beginning, a fact that was underscored in a 2016 global assessment of VBHC published by The Economist Intelligence Unit.

This paper looks at the ways in which Sweden has implemented VBHC, the areas in which it has faced obstacles and the lessons that it can teach other countries and health systems looking to improve the value of their own healthcare investments.

The cost of inaction: Secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in Asia-Pacific

The burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) across Asia-Pacific varies by country, but is nonetheless substantial. Collectively CVD is the leading or second-leading cause of death across the region and the prevalence continues to rise. Further, shifting demographics in the region—with both an increase in younger people experiencing CVD and ageing populations with multiple comorbidities—are putting health systems under increasing pressure.

Related content

高まる二次予防の重要性: アジアにおける心疾患医療の現状・課題

国によって状況は異なるものの、心血管疾患(CVD)がもたらす負担が非常に大きいことは間違いない。CVD は全てのアジア諸国で二大死因となっており、患者数も増加の一途を辿っている。またアジアでは、若年層のCVD 患者・高齢者層の合併症患者が並行して増えており、医療体制にさらなる負担をもたらしている。

近年、CVD に関連する問題への対策は、一次予防の分野で進化を遂げつつあり、年齢調整罹患率にも減少の兆しが見られる。しかし急性心筋梗塞・脳卒中の再発率は依然として高く、その経済的・人的コストも大きいのが実状である。また一度目の発症での生存率が向上している今、再発によって生じる負担はさらに増す可能性が高い。ただし、対応が急務となっているこうした現状に取り組むことが現実的であることを鑑みると、当該患者グループのケア体制・アウトカムを向上させる重要な機会だと捉えることができる。

ザ・エコノミスト・インテリジェンス・ユニット(EIU)の本報告書は、アジア太平洋地域8 カ国(オーストラリア・中国・香港・日本・シンガポール・韓国・台湾・タイ)を対象として、CVD の再発予防に向けた政策的取り組みを検証する。

主要な論点は以下の通り:

多くの国はCVD 政策を掲げているが、包括性の面で大きな差がある。 改善可能なリスク因子への取り組みは、具体的な法案・行動計画、および成果評価に必ずしも結びついていない。 政府による成果評価の仕組みは発展途上である。 包括医療に不可欠なプライマリケアは近年進化を遂げつつある。 多くの国はリハビリサービスを実施しているが、提供能力は限られており、利用者も伸び悩んでいる。 連携を通じた患者中心の包括医療の必要性 取り組みの成功の鍵を握るのは患者エンパワーメント データ活用の加速と成果評価の仕組みも重要な鍵となる

조치 부재의 비용: 아시아 태평양 지역 내 심혈관 질환의 2차 예방

아시아 태평양 지역의 심혈관 질환(CVD)부담은 국가별로 상이하나 모두 상당하다.CVD는 지역 전반에서 사망 원인 1위 또는2위를 차지하고 있으며, 유병률도 계속높아지고 있다. 또한 CVD를 경험하는 젊은환자와 여러 동반 이환을 가진 고령화 인구두 집단 모두의 증가라는 지역 내 인구통계적변화로 인해 각국의 보건의료체계에 부하가걸리고 있다.

CVD 관련 문제 해결에 관한 진척은 1차예방 분야에 초점이 맞춰져 이루어져왔으며, CVD의 연령표준화 발생률은감소하기 시작했다. 그러나 여전히 허용할수 없는 높은 수준의 심장마비 및 뇌졸중재발률과 그에 따른 경제적 및 인적 비용이존재해 이러한 진척을 저해하고 있다. 첫심장마비 또는 뇌졸중 생존자가 더많아짐에 따라 2차 사건 관련 부담이증가할 가능성이 높다. 이는 긴급한 주의를요구하는 상황인 동시에, 해당 환자 집단의관리와 결과를 개선할 수 있는 탁월하고현실적인 기회이기도 하다.

본 이코노미스트 인텔리전스 유닛분석에서는 아시아 태평양 지역8개국(호주, 중국, 홍콩, 일본, 싱가포르,한국, 대만, 태국)의 2차 심혈관 사건관리에 대한 정책적 대응을 살펴본다. 본 연구의 주요 결과는 다음을 포함한다. 관련 정책은 확실히 존재하나, 정책이상당히 포괄적인 국가도 있고 그렇지 않은국가도 있다. 조절 가능한 위험인자에 대한 정책을 법률과실천에 성공적으로 반영했는지 여부와 그로인한 영향은 아직 확인되지 않았다. 정부 감사가 결여되어 있다. 통합 관리의 핵심 요소인 1차 의료 체계가발전하고 있다. 재활 서비스가 존재하나 보장 범위가제한적이며, 업체들은 환자 유치와 유지에어려움을 겪고 있다. 필요한 목표는 환자 중심의 통합적이고조정된 관리 환자 권한부여는 성공의 핵심 데이터 극대화 및 진척도 측정Covid-19 population tracker: deaths from covid-19 and the ones we must not forget

There has been a morbid fascination with the number of deaths associated with covid-19 and the extent to which countries are mishandling the crisis. But we are also facing a data crisis which distorts proper analysis of either.

17404

Related content

Value-based healthcare in Sweden: Reaching the next level

The need to get better value from healthcare investment has never been more important as ageing populations and increasing numbers of people with multiple chronic conditions force governments to make limited financial resources go further.

These pressures, along with a greater focus on patient-centred care, have raised the profile of VBHC, especially in European healthcare systems. Sweden, with its highly comprehensive and egalitarian healthcare system, has been a leader in implementing VBHC from the beginning, a fact that was underscored in a 2016 global assessment of VBHC published by The Economist Intelligence Unit.

This paper looks at the ways in which Sweden has implemented VBHC, the areas in which it has faced obstacles and the lessons that it can teach other countries and health systems looking to improve the value of their own healthcare investments.

Breast cancer patients and survivors in the Asia-Pacific workforce

With more older women also working, how will the rising trend of breast cancer survivorship manifest in workplace policies, practices and culture? What challenges do breast cancer survivors face when trying to reintegrate into the workforce, or to continue working during treatment? How can governments, companies and society at large play a constructive role?

This series of reports looks at the situation for breast cancer survivors in Australia, New Zealand and South Korea. It finds that while progress has been made, more needs to be done, particularly in South Korea, where public stigma around cancer remains high.

The Cost of Silence

Cardiovascular diseases levy a substantial financial toll on individuals, their households and the public finances. These include the costs of hospital treatment, long-term disease management and recurring incidence of heart attacks and stroke. They also include the costs of functional impairment and knock-on costs as families may lose breadwinners or have to withdraw other family members from the workforce to care for a CVD patient. Governments also lose tax revenue due to early retirement and mortality, and can be forced to reallocate public finances from other budgets to maintain an accessible healthcare system in the face of rising costs.

As such, there is a need for more awareness of the ways in which people should actively work to reduce their CVD risk. There is also a need for more primary and secondary preventative support from health agencies, policymakers and nongovernmental groups.

To inform the decisions and strategies of these stakeholders, The Economist Intelligence Unit and EIU Healthcare, its healthcare subsidiary, have conducted a study of the prevalence and costs of the top four modifiable risk factors that contribute to CVDs across the Asian markets of China, Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

Download the report to learn more.

The inroads of organised crime in the era of covid-19

Related content

Criminal asset recovery must become governments' central concern

This, in turn, has the effect of further polarising communities and alienating large segments of the population who already feel disenfranchised by an unequal distribution of global resources.

Are we sure there are no less destructive, more socially acceptable alternatives or, as a minimum, some ways to mitigate the impact of unpopular budgetary cuts?

It’s somehow striking that no political party is arguing that a significant contribution to the preservation of social cohesion should come from the recovery of the staggering amount of global wealth stolen through corruption, drug trafficking and other illicit trade that is currently nurturing rampant transnational criminal syndicates. When crime issues feature in electoral campaigns, it is usually to promise more police officers to patrol the streets and increased prison capacity, for example. But crime-control policies need not only represent a burden to state coffers. They can become a wealth-generating strategy if focused, determined and sustained efforts are made to recover stolen criminal assets, well beyond the currently half-hearted efforts.

Estimates by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime put the amount of money laundered globally in one year at 2-5% of global GDP, or US$2trn. To date, investments made in asset recovery efforts are a drop in the ocean. According to Europol, only 1.1% of criminal profits were confiscated in the EU between 2010 and 2014. If this figure were to increase by just a few percentage points, it could translate into a bonanza for national governments, potentially helping to avoid painful cuts to healthcare programmes, pensions for the elderly, subsidies for kindergartens and so on.

I often recall what former Cosa Nostra member Gaspare Mutolo declared in front of the Italian Anti-Mafia Parliamentary Committee back in 1993: “What bothers us most is when they take the money out of our pockets. One prefers to remain in jail with the money rather than being free without the money.”

So, why aren’t genuine, sustained and aggressive efforts being made to “follow the money” as a major path not only to deprive ever-expanding criminal networks of oxygen, but also to recover badly needed resources? After all, this is money that in one way or another has been syphoned from taxpayers’ pockets.

Let’s be fair. Following the money is akin to driving in a thick fog. Financial investigations are time and resource consuming, and fraught with obstacles. They often involve turning to foreign countries for help in tracing assets, freezing bank accounts held abroad and enforcing foreign confiscation orders. And while some authorities may be genuinely willing to assist, including through dedicated asset recovery offices, many are overstretched and not necessarily hoping for the phone to ring. Others are blatantly non-co-operative and pride themselves on their ability to shelter wealth (without asking too many questions about its origin) behind opaque regulations and corporate veils.

Even if investigators eventually succeed in having criminal assets traced, confiscated and turned over, they shouldn’t claim victory too quickly. The Italian experience is instructive. Currently, Italy is at the forefront of global efforts to confiscate criminal assets. Its legislative framework is one of the world’s most advanced and admired. And yet it is proving quite difficult to ensure that the approximately €30bn in assets seized and confiscated from Mafia organisations are effectively allocated for the purposes envisaged by the law: public and social re-use and, as a last resort, sale. Despite recent attempts to streamline procedures, Italy’s nine-year-old Agency for the Management and the Allocation of Seized and Confiscated Assets is still struggling with scarce resources and a Byzantine bureaucracy.

So, mission impossible? Not really. Many countries have already made criminal confiscations easier from a legal point of view, for example, by shifting from prosecutors to defendants the burden to prove that the assets in question are not derived from criminal conduct. Or by enabling authorities to broadly confiscate assets of criminal organisations without the need to establish a connection between those assets and specific criminal offences.

But above all, there seems to be momentum. The public at large, people from all walks of life and political affiliations, are increasingly frustrated at the sheer magnitude of organised crime, exposed by almost daily revelations of massive corruption and money-laundering schemes.

We need a new generation of aspiring politicians willing to invest time and political capital in championing criminal asset recovery as a central pillar of governments’ action. Initially, implementing such a strategy would require steep increases in the number of highly trained financial investigators, investments in big data analytics, and the allocation of significant resources to asset management and cross-border co-operation bodies. But in the medium term, these investments would yield a big payoff. Recovering even just an additional 5% of the globally stolen wealth could make a material difference to the daily lives of a large number of people who are struggling to make ends meet.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (EIU) or any other member of The Economist Group. The Economist Group (including the EIU) cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this article or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in the article.

The Global Illicit Trade Environment Index 2018

To measure how nations are addressing the issue of illicit trade, the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade (TRACIT) has commissioned The Economist Intelligence Unit to produce the Global Illicit Trade Environment Index, which evaluates 84 economies around the world on their structural capability to protect against illicit trade. The global index expands upon an Asia-specific version originally created by The Economist Intelligence Unit in 2016 to score 17 economies in Asia.

View the Interactive Index >> Download workbook

Value-based healthcare in Sweden: Reaching the next level

The need to get better value from healthcare investment has never been more important as ageing populations and increasing numbers of people with multiple chronic conditions force governments to make limited financial resources go further.

These pressures, along with a greater focus on patient-centred care, have raised the profile of VBHC, especially in European healthcare systems. Sweden, with its highly comprehensive and egalitarian healthcare system, has been a leader in implementing VBHC from the beginning, a fact that was underscored in a 2016 global assessment of VBHC published by The Economist Intelligence Unit.

This paper looks at the ways in which Sweden has implemented VBHC, the areas in which it has faced obstacles and the lessons that it can teach other countries and health systems looking to improve the value of their own healthcare investments.

The world must devise a globally fair covid-19 vaccine allocation system

Related content

Value-based healthcare in Sweden: Reaching the next level

The need to get better value from healthcare investment has never been more important as ageing populations and increasing numbers of people with multiple chronic conditions force governments to make limited financial resources go further.

These pressures, along with a greater focus on patient-centred care, have raised the profile of VBHC, especially in European healthcare systems. Sweden, with its highly comprehensive and egalitarian healthcare system, has been a leader in implementing VBHC from the beginning, a fact that was underscored in a 2016 global assessment of VBHC published by The Economist Intelligence Unit.

This paper looks at the ways in which Sweden has implemented VBHC, the areas in which it has faced obstacles and the lessons that it can teach other countries and health systems looking to improve the value of their own healthcare investments.

Breast cancer patients and survivors in the Asia-Pacific workforce

With more older women also working, how will the rising trend of breast cancer survivorship manifest in workplace policies, practices and culture? What challenges do breast cancer survivors face when trying to reintegrate into the workforce, or to continue working during treatment? How can governments, companies and society at large play a constructive role?

This series of reports looks at the situation for breast cancer survivors in Australia, New Zealand and South Korea. It finds that while progress has been made, more needs to be done, particularly in South Korea, where public stigma around cancer remains high.

The Cost of Silence

Cardiovascular diseases levy a substantial financial toll on individuals, their households and the public finances. These include the costs of hospital treatment, long-term disease management and recurring incidence of heart attacks and stroke. They also include the costs of functional impairment and knock-on costs as families may lose breadwinners or have to withdraw other family members from the workforce to care for a CVD patient. Governments also lose tax revenue due to early retirement and mortality, and can be forced to reallocate public finances from other budgets to maintain an accessible healthcare system in the face of rising costs.

As such, there is a need for more awareness of the ways in which people should actively work to reduce their CVD risk. There is also a need for more primary and secondary preventative support from health agencies, policymakers and nongovernmental groups.

To inform the decisions and strategies of these stakeholders, The Economist Intelligence Unit and EIU Healthcare, its healthcare subsidiary, have conducted a study of the prevalence and costs of the top four modifiable risk factors that contribute to CVDs across the Asian markets of China, Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

Download the report to learn more.

Suffering in silence: Assessing rare disease awareness and management in Asia-Pacific

As the region begins to get to grips with rare diseases, it will need to address significant challenges, some of which are still emerging. Health and social systems are making progress in many of these areas, but finding solutions remains a work in progress.

Related content

Video | Suffering in silence report highlights

Suffering in Silence: Assessing rare-diseases awareness and management in Asia-Pacific

Full reports:

Snapshots:

Australia | China | Japan | Korea | Taiwan

无声的苦难:中国大陆罕见病的认知与管理评估

日本における希少疾患の現状: 認知度・QoL向上に向けた課題と取り組み

침묵 속의 고통: 한국의 희귀질환 인 식 및 관리현황 평가

無聲的苦難:評估台灣對於罕見疾病之認知與管理

Video highlights:

English | Simplified Chinese | Japanese | Korean | Traditional Chinese

アジアにおける希少疾患: 認知度・QoL向上に向けた 課題と取り組み

そうした中で域内諸国は希少疾患がもたらす新旧様々な問題に直面している。医療・社会制度改革を通じた問題への対応が進んでいるものの、依然として効果的対策の模索が続く分野も多い。

ザ・エコノミスト・インテリジェンス・ユニット(EIU)がCSL ベーリングの協賛の下で作成した本報告書では、アジア太平洋地域5 カ国が希少疾患の分野で直面する課題と対応、診療体制の改革に向けた取り組みについて検証する。本報告書の作成に当たっては、医療関係者500名以上を対象としたアンケート調査、学術機関・医療機関・政府関係者・エキスパート患者16名に対する聞き取り調査、そして詳細にわたるデスクリサーチが実施された。

本報告書の作成にあたり、ザ・エコノミスト・インテリジェンス・ユニット(EIU)はアジア太平洋地域5 カ国の医療関係者503名を対象とするアンケート調査を2019 年11 〜12 月にかけて実施した。その目的は、希少疾患の認知レベルを理解し、各国政府が直面する課題を検証することだ。調査対象者の内訳は、専門医172 名、一般開業医229 名、看護師40 名、薬剤師62 名(いずれも現職)。国別の内訳は、オーストラリア103 名、中国100 名、日本100 名、韓国100 名、台湾100 名となっている。

また今回の調査では、医療者・患者団体関係者16 名を対象として、詳細にわたる聞き取り調査も実施した。ご協力をいただいた下記の皆様(アルファベット順に掲載・敬称略)には、この場を借りて御礼申し上げます:

国立研究開発法人 日本医療研究開発機構プログラムオフィサー 足立剛也 韓国国立生物医学医療センター希少疾患部門 Younjhin Ahn クイーンズランド工科大学eResearch 学部 ディレクターAPEC 希少疾患ネットワーク 議長Matthew Bellgard 西オーストラリア遺伝子検査サービスセンター未診断疾患プログラム担当ディレクターGareth Baynam 香港中文大学 準教授 Dong Dong シドニー大学小児科学・児童健康学担当教授Elizabeth Elliott 中国希少疾患協会 創立者 Kevin Huang アジア太平洋希少疾患連合理事長 Ritu Jain 千葉大学医学部附属病院脳神経内科 准教授 三澤園子 特定非営利活動法人 ASrid理事 西村由希子 台湾希少疾患基金共同創立者 Min-Chieh Tseng Rainbow Across Borders議長 Gregory Vijayendran Rare Cancers Australia理事長 Richard Vines 台中栄民総医院希少疾患・血友病センター ディレクターJiaan-Der Wang 疾病挑戦基金 事務局長 Yi'ou Wang 台湾健康増進部 事務次長 Chao-Chun Wu本調査プロジェクトはCSL ベーリングの協賛の下で実施された。報告書の執筆はPaul Kielstra、編集はEIU のJesse Quigley Jones が担当している。

Full reports:

Snapshots:

Australia | China | Japan | Korea | Taiwan

无声的苦难:中国大陆罕见病的认知与管理评估

日本における希少疾患の現状: 認知度・QoL向上に向けた課題と取り組み

침묵 속의 고통: 한국의 희귀질환 인 식 및 관리현황 평가

無聲的苦難:評估台灣對於罕見疾病之認知與管理

Video highlights:

English | Simplified Chinese | Japanese | Korean | Traditional Chinese

침묵 속의 고통: 아시아태평양 지 역내 희귀질환 인지도 및 질병관 리 현황 평가

희귀질환에 대한 이해와 함께 아태지역국가들은 중대한 과제들을 해결해야 하며 일부과제들은 아직도 부상 중이다. 많은 아태국가들의 보건사회제도가 발전하고 있지만해결책을 모색하는 과정은 아직도 진행 중이다

The Economist Intelligence Unit 의 이번보고서는 CSL Behring 의 후원으로 아태지역에서의 희귀질환의 양상을 살펴보고, 다섯아태 국가의 희귀질환 대응 수준 및 환자진료개선을 위한 정책들을 검토한다. 본 보고서는500 명 이상의 임상가, 16 명의 학계, 의료계, 정부, 환자 전문가들을 대상으로 한 설문조사와 광범위한 자료조사를 토대로작성되었다.

2019 년 11,12 월에 걸쳐 EIU 는 아시아태평양 지역에서의 희귀질환에 대한이해수준과 의료제도 차원의 과제를파악하기 위해 지역내 다섯 국가의 503 명의의료 전문가들을 대상으로 설문조사를실시했다. 설문 참가자들은 현직 전문의172 명, 일반의 229 명, 간호사 40 명, 약사62 명으로서, 국가별 분포는 호주 103 명,중국 100 명, 일본 100 명, 한국 100 명, 대만100 명과 같다.이와 더불어 16 명의 임상 전문가 및 환자단체 대표들과 자문/ 심층 인터뷰를 실시하였다. 지면을 빌어 아래의 전문가/대표들의 시간과 고견에 심심한 감사의 말씀을 전한다:

Takeya Adachi, 일본 의학연구개발소프로그램 담당 안윤진,한국 국립보건연구원생명의과학센터 난치성질환과 Matthew Bellgard, 호주 퀸즐랜드공과대학교 교수 및 전자연구소장, 아시아태평양경제협력체 (APEC) 희귀질환네트워크 의장 Gareth Baynam, 호주 웨스턴오스트레일리아 주 미진단 질환프로그램 유전학 서비스 과장 및 임상유전학 전문가 Dong Dong, 홍콩 특별자치구중문대학교 연구조교수 Elizabeth Elliott, 호주 시드니 대학교소아 청소년과 교수 Kevin Huang, 중국 희귀질환연합 창립자 Ritu Jain,싱가포르 아시아태평양 희귀질환연합 대표 Sonoko Misawa, 일본 지바대학교의과대학원 부교수 Yukiko Nishimura, NPO ASrid (일본희귀난치성 질환 이해관계자 권리증진서비스)창립 대표 Min-Chieh Tseng, 대만 희귀질환재단공동설립자 Gregory Vijayendran, Rainbow Across Borders대표 Richard Vines, 호주 Rare Cancers Australia 대표 Jiaan-Der Wang, 대만 타이충 보훈병원희귀질환 및 혈우병 센터장 Yi’ou Wang, Illness Challenge Foundation사무국장 Chao-Chun Wu, 대만 건강증진청 사무차장본 연구는CSL Behring사의 후원으로이루어졌으며 보고서 작성은 Paul Kielstra (EIU), 편집은 Jesse Quigley Jones(EIU)가 담당하였다.

Full reports:

Snapshots:

Australia | China | Japan | Korea | Taiwan

无声的苦难:中国大陆罕见病的认知与管理评估

日本における希少疾患の現状: 認知度・QoL向上に向けた課題と取り組み

침묵 속의 고통: 한국의 희귀질환 인 식 및 관리현황 평가

無聲的苦難:評估台灣對於罕見疾病之認知與管理

Video highlights:

English | Simplified Chinese | Japanese | Korean | Traditional Chinese

Amid devastation covid-19 provides glimpse of a future with cleaner air

Related content

Value-based healthcare in Sweden: Reaching the next level

The need to get better value from healthcare investment has never been more important as ageing populations and increasing numbers of people with multiple chronic conditions force governments to make limited financial resources go further.

These pressures, along with a greater focus on patient-centred care, have raised the profile of VBHC, especially in European healthcare systems. Sweden, with its highly comprehensive and egalitarian healthcare system, has been a leader in implementing VBHC from the beginning, a fact that was underscored in a 2016 global assessment of VBHC published by The Economist Intelligence Unit.

This paper looks at the ways in which Sweden has implemented VBHC, the areas in which it has faced obstacles and the lessons that it can teach other countries and health systems looking to improve the value of their own healthcare investments.

Breast cancer patients and survivors in the Asia-Pacific workforce

With more older women also working, how will the rising trend of breast cancer survivorship manifest in workplace policies, practices and culture? What challenges do breast cancer survivors face when trying to reintegrate into the workforce, or to continue working during treatment? How can governments, companies and society at large play a constructive role?

This series of reports looks at the situation for breast cancer survivors in Australia, New Zealand and South Korea. It finds that while progress has been made, more needs to be done, particularly in South Korea, where public stigma around cancer remains high.

The Cost of Silence

Cardiovascular diseases levy a substantial financial toll on individuals, their households and the public finances. These include the costs of hospital treatment, long-term disease management and recurring incidence of heart attacks and stroke. They also include the costs of functional impairment and knock-on costs as families may lose breadwinners or have to withdraw other family members from the workforce to care for a CVD patient. Governments also lose tax revenue due to early retirement and mortality, and can be forced to reallocate public finances from other budgets to maintain an accessible healthcare system in the face of rising costs.

As such, there is a need for more awareness of the ways in which people should actively work to reduce their CVD risk. There is also a need for more primary and secondary preventative support from health agencies, policymakers and nongovernmental groups.

To inform the decisions and strategies of these stakeholders, The Economist Intelligence Unit and EIU Healthcare, its healthcare subsidiary, have conducted a study of the prevalence and costs of the top four modifiable risk factors that contribute to CVDs across the Asian markets of China, Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

Download the report to learn more.