Inforaphic Mobile Image

The ability to extract value from artificial intelligence (AI) will sort the winners from the losers in banking, according to 77% of bank executives surveyed by The Economist Intelligence Unit in February and March 2020. AI platforms were the second highest priority area of technology investment, the survey found, behind only cybersecurity.

At the time, the covid-19 pandemic was in full effect in Asia and the rest of the world was beginning to understand its gravity. Since then, the depth and extent of covid-19’s impact on consumer behaviour and the global economy have come into clearer focus.

Covid-19 has already triggered an uptick in digital banking—in the US Citibank is reported to have seen a tenfold surge in activity on Apple Pay during lockdown, for example1. But the disruption to businesses and households has only just begun, and banks will need to adapt to rapidly changing customer needs.

As such, the criticality of AI adoption is only likely to increase in the post-pandemic era: its safe and ethical deployment is now more urgent than ever.

In common with most matters of governance and safety, banks will look to regulatory authorities for guidance on how this can be achieved. Until a few years ago regulators adopted a wait-and-see approach but, more recently, many have issued a number of studies and discussion papers.

In order to assess the key risks and governance approaches that banking executives must understand, The Economist Intelligence Unit undertook a structured review of 25 reports, discussion papers and articles on the topic of managing AI risks in banking. The main findings are summarised in the table on page 3 and examined throughout this article.

Risks known and unknown

The nature of the risks involved in banks’ use of AI does not differ materially from those faced in other industries. It is the outcomes that differ should risks materialise: financial damage could be caused to consumers, financial institutions themselves or even to the stability of the global financial system.

Our review reveals that prominent risks include bias in the data that is fed into AI systems. This could result in decisions that unfairly disadvantage individuals or groups of people (for example through discriminatory

Some AI models have a complexity that many organisations, including banks, have never seen before. Prag Sharma, senior vice-president and emerging technology lead, Citi Innovation Labs

lending). “Black box” risk arises when the steps algorithms take cannot be traced and the decisions they reach cannot be explained. Excluding humans from processes involving AI weakens their monitoring and could threaten the integrity of models (see table for a comprehensive list of AI risks in banking).

At the root of these and other risks is AI’s increasingly inherent complexity, says Prag Sharma, senior vice-president and emerging technology lead at Citi Innovation Labs. “Some AI models can look at millions or sometimes billions of parameters to reach a decision,” he says. “Such models have a complexity that many organisations, including banks, have never seen before.” Andreas Papaetis, a policy expert with the European Banking Authority (EBA), believes this complexity—and especially the obstacles it poses to explainability—are among the chief constraints on European banks’ use of AI to date.

Governance challenges

The guidance that regulators have offered so far can be described as “light touch”, taking the form of information and recommendations rather than rules or standards. One possible reason for this is to avoid stifling innovation. “The guidance from governing bodies where we operate continues to encourage innovation and growth in this sector,” says Mr Sharma.

Another reason is uncertainty about how AI will evolve. “AI is still at an early stage in banking and is likely to grow,” says Mr Papaetis. “There isn’t anyone who can answer everything about it now.”

The documents that banking regulators have published on AI range from the succinct (an 11-page statement of principles by MAS—the Monetary Authority of Singapore) to the voluminous (a 195-page report by Germany’s BaFin—its Federal Financial Supervisory Authority), but the guidance they offer converges in several areas.

At the highest level, banks should establish ethical standards for their use of AI and systematically ensure that their models comply. The EBA suggests using an “ethical by design” approach to embed these principles in AI projects from the start. It also recommends establishing an ethics committee to validate AI use cases and monitor their adherence to ethical standards.4

For regulators, paramount among the ethical standards must be fairness—ensuring that decisions in lending and other areas do not unjustly discriminate against individuals or specific groups of people. De Nederlandsche Bank (or DNB, the central bank of the Netherlands) emphasises the need for regular reviews of AI model decisions by domain experts (the “human in the loop”) to help guard against unintentional bias.5 The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) advises that model data be tested and evaluated regularly, including with the use of bias-detection software.6 “If you have a good understanding of your underlying data,” says Mr Sharma, “then a lot of the algorithmic difficulties in terms of ethical behaviour or explainability can be addressed more easily”.

Monitoring the modellers at Citi

Bias can creep into AI models in any industry but banks are better positioned than most types of organisations to combat it, believes Prag Sharma, senior vice-president and emerging technology lead at Citi Innovation Labs. “Banks have very robust processes in place, learned over time, that meet strict external [regulatory] and internal compliance requirements,” he says.

At Citi, a model risk management committee reports directly into the bank’s chief risk officer and operates separately from the modellers and data science teams. Consisting of risk experts as well as data scientists, the committee’s task, says Mr Sharma, is to scrutinise the models that his team and others are developing exclusively from a risk perspective. The committee’s existence long predates the emergence of AI, he says, but the latter has added a challenging new dimension to the committee’s work.

Maximising algorithms’ explainability helps to reduce bias. Once a team is ready to deploy a model into production, the model risk management committee studies it closely with explainability one of its key areas of focus. “[The risk managers] instruct us to explain all the model’s workings to them in a way that they will completely understand,” says Mr Sharma. “Nothing hits our production systems without a green light from this committee.”

Ensuring the right level of explainability, as Mr Papaetis suggests, is arguably banks’ toughest AI challenge. Most of the regulator guidance stresses the need for thorough documentation of all the steps taken in model design.

Ensuring the right level of explainability is arguably banks’ toughest AI challenge.

The EBA, says Mr Papaetis, recommends taking a “risk-based approach” in which different levels of explainability are required depending on the impact of each AI application—more, for example, for activities that directly impact customers and less for low-risk internal activities.

Are more prescriptive approaches needed?

Regulators generally consider banks’ existing governance regimes to be adequate to address the issues raised by AI. Rather than creating new AI-specific regimes, most regulators agree that current efforts should instead be focused on updating their governance practices and structures to reflect the challenges posed by AI. Ensuring that the individuals responsible for oversight have adequate AI expertise is integral, according to DNB.

Fit for purpose? Applying existing governance principles to AI

In Europe, bank adoption of AI-based systems may be described as broad but shallow. In a recently published study the European Banking Authority (EBA) found that about two-thirds of the 60 largest EU banks had begun deploying AI but in a limited fashion and “with a focus on predictive analytics that rely on simple models”.7 This is one reason why Andreas Papaetis, a policy expert with the EBA, believes it is too early to consider developing new rules of governance for the EU’s banks that focus on AI.

Mr Papaetis points out that the EBA’s existing guidelines on internal governance and ICT (information and communications technology) risk management are adequate for AI’s current level of development in banking. The existing framework is sufficiently flexible and not overly prescriptive, he says. “That enables us to adapt and capture new activities or services as they develop. So at the moment we don’t think that AI or machine learning require anything additional when it comes to governance.” In any event, the EBA’s approach, he says, will be guided by European Commission policy positions on the role of AI in the economy and society.8

Mr Papaetis does not exclude the possibility of more detailed regulatory guidance on AI in areas such as data management and ethics. Should bias and a lack of explainability prove to be persistent problems, for example, regulators may need to consider drafting more specific rules. But at present, he says, “no one can predict what challenges AI will throw up in the future”.

More regulatory guidance will almost certainly be needed in the future, says Mr Sharma, and some of it may require the drafting of rules. He offers as an example the uncertainty among experts around the retraining of existing AI models. “Does retraining a model lead to the same or a new model from a risk perspective?” he asks. “Does a model need to go through the same risk review process each time it is retrained, even if that happens weekly, or is a lighter-touch approach possible and appropriate?”

Should a major failure be attributed to AI— such as significant financial losses suffered by a group of customers due to algorithm bias, evidence of systematic discrimination in credit decisions or algorithm-induced errors that threaten a bank’s stability—authorities would no doubt revisit their previous guidance and possibly put regulatory teeth into their non-binding recommendations.

The need to monitor and mitigate such risks effectively makes it incumbent on regulators to build AI expertise that meets or betters that of commercial banks. As AI evolves, strong governance will inevitably be demanded at all levels of the banking ecosystem.

[1] Antoine Gara, “The World’s Best Banks: The Future Of Banking Is Digital After Coronavirus”, Forbes, June 8th 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ antoinegara/2020/06/08/the-worlds-best-banks-the-future-of-banking-is-digital-after-coronavirus/

[2]Top three responses shown. For full results “Forging new frontiers: advanced technologies will revolutionise banking”, The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020. https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/financial-services/forging-new-fro...

[3] The Economist Intelligence Unit reviewed 25 reports, discussion papers and articles published in the past three years by banking and financial sector supervisory authorities, central banks and supranational institutions, as well a handful of reports from universities and consultancies, on the theme of managing the risks associated with AI. The points of guidance listed below are distilled from studies and discussion papers published in the past two years by financial sector supervisory authorities, regulatory agencies and supranational institutions. These include the European Banking Authority, Monetary Authority of Singapore, DNB (Bank of the Netherlands), Hong Kong Monetary Authority, CSSF (Financial Sector Supervisory Authority of Luxembourg), BaFin (Federal Financial Supervisory Authority of Germany), ACPR (Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority of France), and the European Commission.

[4] European Banking Authority, EBA Report on Big Data and Advanced Analytics, January 2020. https://eba.europa.eu/file/609786/ download?token=Mwkt_BzI

[5] De Nederlandsche Bank, General principles for the use of Artificial Intelligence in the financial sector, July 2019. https://www.dnb.nl/en/binaries/ General%20principles%20for%20the%20use%20of%20Artificial%20Intelligence%20in%20the%20financial%20sector2_tcm47-385055.pdf

[6] Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Reshaping Banking with Artificial Intelligence, December 2019. https://www.hkma.gov.hk/media/eng/doc/keyfunctions/finanical-infrastruct...

[7] ibid.

[8] The commission launched a public debate on AI policy options in early 2020 and is expected to announce its policy decisions later this year.

The coronavirus crisis has focused the attention of banks firmly on new challenges. Bank branch traffic was already falling before the pandemic, and this trend will only intensify with society in lockdown: customers are unable to leave their homes while employees are working remotely or frequently absent due to illness. “Banks have planned for years for disaster recovery if their technology failed but have never planned for disaster recovery if their buildings closed,” says Chris Skinner, a leading influencer and champion of digitalisation in finance. “This is the big lesson of the crisis.”

The lockdown will most likely accelerate the digitisation of banking,1 a sector which already faces intense competition from payment players, big technology and e-commerce firms. According to the latest global banking survey conducted by The Economist Intelligence Unit (now in its seventh year and for the first time expanded to include respondents from commercial and private banks), 45% of respondents say their strategic response to this challenge is to build a “true digital ecosystem”. This aim to integrate self-built digital services and third-party offerings was cited more than any other response and has increased from 41% of respondents in 2019.

This article explores three central elements of banking digitisation: where banks currently are in their digital journey; what they are doing, not only to overcome challenges but also to increase user engagement through different technologies and channels; and how they are seizing opportunities through reorganisation into more agile structures.

Methodology

In February-March 2020 The Economist Intelligence Unit, on behalf of Temenos, surveyed 305 global banking executives on themes relating to the digitisation of banking. The survey included respondents from retail, corporate and private banks in Europe (25%), North America (24%), Asia-Pacific (18%), Africa and the Middle East (16%) and Latin America (17%). Respondents performed different job functions: marketing and sales (18%), IT (13%), customer service (7%) and finance (14%), while almost half were C-suite executives (49%). The coronavirus pandemic emerged half-way through the survey.

The survey is part of a worldwide research programme on new frontiers in a global age of banking. It draws on in-depth interviews with retail, corporate and private wealth banks, regulators, international organisations and consultancies around the world. The survey research and interviews will be featured in a series of articles and an infographic throughout 2020.

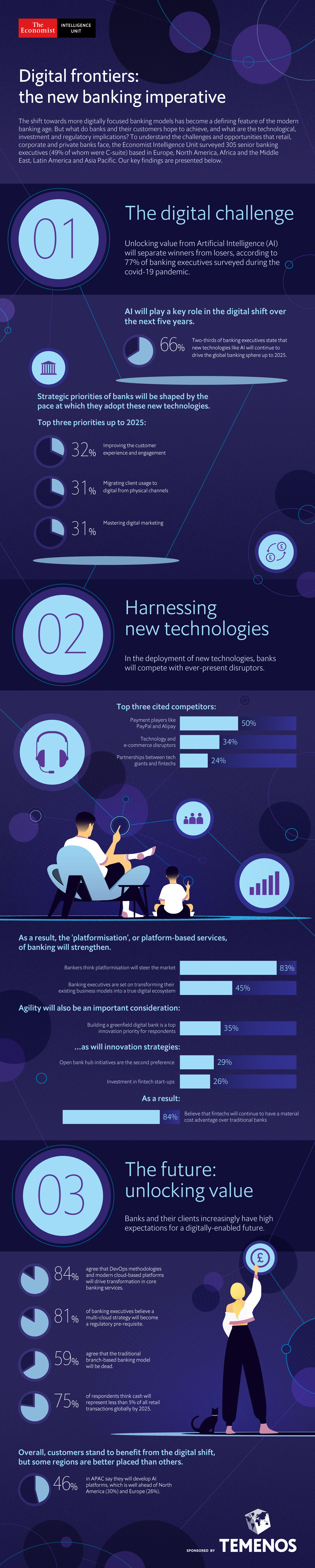

New technologies will continue to drive global banking for the next five years while regulatory concerns around these technologies remain top of mind for banking executives.

A large majority of respondents (66%, up from 42% in 2019) cite new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, blockchain or the Internet of Things (IoT) as having a significant impact on the sector. This highlights the importance of these new tools in fending off the competitive threat posed by tech-driven, non-traditional entrants to the banking sector such as payment players PayPal and ApplePay (cited by 50% of respondents globally), or big tech firms like Google, Facebook and Alibaba (34%).

Regulation of digital technology (such as data protection) has weighed on banks’ profit and loss (P&L) since the 2008 financial crisis and is now considered the second most impactful trend in the industry (as cited by 42% of respondents). New regulation could be a game changer for the development of open banking in certain regions, but it could also allow non-traditional competitors to enter the sector.

There is slightly less apprehension about neobanks (a concern cited by 20%) which have not managed to dent savings or lending volumes to a significant extent. Some early challengers are shifting their strategies from directly offering financial products to selling their expertise to existing banks with bigger brands, more reach and higher capital.2 In fact, 84% believe that fintechs will continue to have a material cost advantage over traditional banks: investing in fintechs is a priority innovation strategy for over a quarter of respondents (26%), and even more so in the retail space (33%).

As the importance of advanced technologies rises, that of changing customer behaviours and demands—while still viewed as impactful by 28% of respondents—continues to decline. In 2019, 31% of respondents cited it as highly significant compared with 58% in 2018. This may be due to the fact that banking clients now display higher digital adoption rates and have established digital expectations. Moreover, a majority of respondents (59%) agree with the statement that “the traditional branch-based banking model will be dead” by 2025, up from 44% in 2019.

In the shift towards enterprise agility, DevOps—a set of practices which bring together software development and IT operations—and modern cloud-based platforms could be transformative, according to 84% of respondents. The computing power and flexibility of cloud-based technologies and services remain of prime interest to banks with 27% of respondents focusing their technology investment in this area (see also below). Unsurprisingly, 81% believe a multi-cloud strategy will become a regulatory prerequisite after several years of regulatory focus on cloud technologies in the UK and the US.3

Banks are adapting their internal structures to digital technologies in order to enhance customer experience, product offering and new revenue streams.

An overwhelming majority of respondents (83%) believe that platformisation of banking and other services through a single entry point will steer the market. This is driving banks towards transforming their existing business models into true digital ecosystems according to 45% of respondents.

Where are banks focusing their digital efforts? For many, technology investment hinges on cybersecurity (35%), which reflects widespread concerns about data breaches. The development of AI platforms like digital advisors and voice assisted engagement channels is cited by 33% of respondents and cloud-based technologies by 27%. AI will undoubtedly play a central role in the digital shift: 77% of respondents agree that unlocking value from AI will be a key differentiator between winning and losing banks.

However, banks may be missing a trick by focusing purely on AI’s customer-facing capabilities while downplaying other benefits in the value chain, which focus more on productivity, customer retention and monitoring functions (see chart 2 below). There are concerns among customers about how AI technologies will use their data and whether it is safe: 34% of respondents expressed concern about lack of clarity surrounding data use while 40% were unsure about the security of their personal financial information. Despite these reservations, there are signs of greater product innovation within the sector: 30% of respondents expect to maintain their own product offerings and become an aggregator of third-party banking or non-banking products (up from 28% last year).

Increasing numbers of banks anticipate AI will help generate new business. “As investment algorithms get more advanced, they will be used more widely in portfolio management. Not to use the over-hyped AI term, but advanced algorithms for investment strategies will gain strength,” explains Nic Dreckmann, chief operating officer and head of intermediaries at private bank Julius Bär.

For the entire customer journey to succeed, respondents report that broader deployment of AI in fraud detection (16%) and backoffice functions (8%) are likely to feature more heavily in future business plans. At HSBC Private Bank, AI is already integrated in back office functions, according to chief operating officer Anil Venuturupalli. For banks worldwide of all sizes, cultural change will be central to deploying technologies such as AI effectively.

Building greenfield banks is an increasingly popular strategy to achieve digital agility.

Last year, building a greenfield digital bank was a top innovation strategy among retail bankers (cited by 36%). A priority again this year for respondents globally (35%), it was particularly strongly expressed by respondents in the wealth sector: 52% believe this to be the best way to compete most cost effectively (see chart 4).

Open bank hub initiatives that give customers access to third-party offerings remain important as respondents’ second preference (29%). This is followed by investment in fintech start-ups, which 26% of respondents cite as part of their innovation strategy. Although less of a concern than in 2019, 25% of banks are looking to participate in sandboxes to collaborate with fintechs and other technology providers to test new propositions.

Banks are also developing digital strategies to move away from their current operating models and promote greater agility. Improving product agility and the ability to launch new products is cited as the third most important strategic priority (26%), after improving customer experience and engagement (32%), and mastering digital marketing (31%). Migrating client usage to digital from physical channels tops the list of priorities for retail banks (35%, compared with 31% globally). Some banks, such as HSBC, have started to build out from existing operations and draw in third-party expertise where necessary to deliver digital private banking around the world. “We are looking at developing a hybrid engagement model where technology will handle all of the administrative touchpoints for our clients,” says Mr Venuturupalli.

Traditional means of banking such as cash will fall by the wayside as agility becomes increasingly aligned with the digitisation of transactions and products. A majority of respondents (75%) think paper notes will represent less than 5% of all retail transactions globally by 2025.

As technology and demand changes at an ever-faster pace, banks in general will need to adopt new working practices and administrative structures that align with their business strategies and priorities, particularly if they are to capitalise on different digital advantages by 2025.

However, it seems developing agile structures that break down internal barriers is not yet a widespread priority given that only 17% of respondents said this was a focal point for their technology investment. This further raises the question of whether banks will be able to achieve their strategic greenfield bank and broad ecosystem plans on time and within budget drawing only on in-house resources.

AI with a profitable purpose

Many banks are clear on what they want to achieve from AI. The dual priorities for CaixaBank of Spain are freeing up staff time and improving employee productivity. The bank processes over 12,000 transactions per second in peak hours and boasts a 900 terabytes data pool to improve the customer experience.

The bank’s 100-strong business intelligence unit uses big data, AI and machine learning to communicate with customers more efficiently. As a result, branch staff levels are half the euro zone average and CaixaBank’s costs are the lowest of its domestic peer group. AIdriven virtual assistants used by advisors and customers have more than doubled sales conversion rates in just one year.

Lessons from lockdown

While the coronavirus pandemic has highlighted how quickly financial institutions need to adjust when the unexpected hits, it has also demonstrated many opportunities to be seized from a digital banking perspective.

As lockdowns were introduced, bank phone services were overwhelmed in the UK and the US.4 Operational processes struggled to incorporate government relief financial schemes, but some banks managed to demonstrate the real value of agility.

Citizens Bank of Edmond, Oklahoma, has just one branch and 55 members of staff. The bank was quick to send out loan relief forms to borrowers and modify overdraft arrangements to offer early access to direct payments from the US government: its speed of response left larger competitors trailing behind. Chief executive Jill Castilla made use of the bank’s social media platforms to offer advice and reassurance—and a personal line of contact for worried customers. Some banks, such as US-based Atlantic Union Bank, moved to streamline their loan application workflows with new digital platforms,5 while others looked to increase their customer outreach via digital channels.6

However, the need to introduce a human touch to the digital experience predates the covid-19 pandemic. Banks were already looking for innovative ways to achieve this, often by providing opt-in communication channels to clients. For example, two US banks— Oregonbased Umpqua Bank and Iowa-based Hills Bank—have been using mobile banking apps that give customers direct access to a digital banker of their choice for a variety of services including bank-account opening and transfer of funds.7 In Turkey, VafikBank has a fleet of direct sales agents who visit digital banking customers at their office or home to provide expert advice on more complex products such as loans.

US digital banking gets a boost

Fintechs have found it harder to challenge the established banks in the US than they have in Europe and Asia. That may be about to change.

Last year, we highlighted progress at Varo Money, a mobile banking firm that offers loans alongside checking and savings accounts. After a three year wait, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation approved Varo’s application for a bank charter earlier this year. Once final approval is granted, the licence will eventually allow Varo to offer its accounts to US customers with the same US$250,000 deposit guarantee that established bank customers enjoy.

Varo subsequently received more good news from a surprising source. In March 2020 its New York-based fintech competitor Moven surprised the market by closing its consumer-facing business, blaming market conditions for a lack of development funding.

Moven then chose Varo as the destination of choice for customers facing account closures, citing its core focus on financial wellness. “We care deeply about our Moven banking customers which is why we made the thoughtful decision, as we transition away from our consumer business, to recommend Varo for their banking needs,” said Moven CEO Marek Forysiak.

For Varo Money, finally receiving that national bank charter will be the icing on the cake. Its founder and CEO Colin Walsh comments that “becoming a fully chartered bank will give us greater opportunity to deliver products and services that positively impact the lives of everyday people around the country”.

Click here to view the infographic.

[1] See, for example: https://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/shares/2020/03/11/will-uk-banks-cat... ; https://gulfbusiness.com/howfintech-is-revamping-the-financial-landscape... ; https://www.finextra.com/newsarticle/35561/rush-to-digitisation-will-see...

[2] Moven shuts all consumer accounts, pivots to B2B-only service for banks, Fintech Futures, 26 March 2020 https://www.fintechfutures.com/2020/03/moven-shuts-all-consumer-accounts...

[3] See, for example, https://www.fintechfutures.com/2016/12/fca-green-lights-cloud-technologies/ and https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-usacongress-cloud/u-s-house-lawmakers-...

[4] The inability of some banks to process loans at the start of the crisis was widely reported in the press, for example: https://www.theguardian.com/ business/2020/apr/15/covid-19-bailout-loans-issued-uk-firms-banks

[5] https://www.forbes.com/sites/tomgroenfeldt/2020/04/20/sba-ppp-loans-at-a...

[6] https://ibsintelligence.com/ibs-journal/ibs-news/icici-bank-launches-its...

[7] https://thefinancialbrand.com/94429/umpqua-human-digital-bank-mobile-cha...

In some instances the impact of this shift will be shaped by local factors, such as demographic changes. In other instances this shift will reflect shared characteristics, as demonstrated by the greater popularity of overseas investing among younger high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) brought up in an era of globalisation. Whatever the drivers, the landscape of wealth is changing—from local to global, and from one focused on returns to one founded on personal values.

Despite rising economic concerns and a tradition of investor home bias in large parts of the world, the new landscape of wealth appears less interested in borders. According to a survey commissioned by RBC Wealth Management and conducted by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), younger HNWIs are substantially more enthusiastic about foreign investing. The U.S. is a particularly high-profile example of a country where a long-standing preference for investments in local markets appears set to be transformed.

Click the thumbnail below to download the global executive summary.

Read additional articles from The EIU with detail on the shifting landscape of global wealth in Asia, Canada, the U.S. and UK on RBC's website.

Enjoy in-depth insights and expert analysis - subscribe to our Perspectives newsletter, delivered every week

The Economist Group is a global organisation and operates a strict privacy policy around the world. Please see our privacy policy here