Businesses around the world——including the 181 CEOs in the Business Roundtable—increasingly assert their intention to deliver positive environmental and social impact. We are bombarded with headlines about companies wanting to “do good by doing well” and to achieve “profit with purpose”. In particular, business leaders speak of, and report on, their organisation’s “social impact”. It seems everyone wants to make a (positive) social impact.

But what do they mean by this? How do they operationalise the term? And how can we measure it and hold businesses to account? Contrary to the positive energy and intentions, without a robust understanding of what we mean by impact the risk of “impact washing” looms, in which businesses continue their same old practices but reframe their activities in the language of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and purpose.

Despite efforts to standardise an understanding of “social impact”, there remains a need to widely socialise a shared meaning of the term. This blog strives to help by offering an account of its origins and evolution.

When did we start talking about “social impact”?

The term “social impact” was first used in a 1969 Yale University seminar on the ethical responsibilities of institutional investors. The following year, the US National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) articulated a set of practices and procedures called the Social Impact Assessment (SIA). The SIA was a legal requirement to systematically capture the potential socio-economic impact of large-scale industrial land-uses. The NEPA mandated the filing of an environmental impact statement for each large land-use decision. This fuelled the prevalence of social impact (predictive) measurements and reporting in the US in the 1970s. This government-required assessment focused on environmental impact and the potential socio-economic costs of displacement. The orientation was a negative one, with land developers reporting the ways in which they were to mitigate the environmental degradation caused by their builds.

Though the US was the early mover in SIA, the volume of SIA reporting activities in the country started to decline from the mid-1980s. The slowdown may be due to both a reduction in the number of large energy-related building projects and the scant availability of (and demand for) social scientists responsible for producing SIAs. While SIA activities slowed in the US, international organisations, including the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, began implementing comprehensive socio-economic and impact assessment reporting on their projects from the 1990s onwards.

The 1990s also saw a rise in the creation of frameworks and guidelines on how to implement a social impact assessment. Most notably, a group of social scientists formed the Inter-Organisational Committee on Principles and Guidelines for Social Impact Assessment to fill a gap between government reporting requirements and the expertise needed to account for impacts. In 1993 they produced the first Principles and Guidelines for Social Impact Assessment, which appraised the social consequences of proposed construction sites, large transportation projects and other uses of land as required by the NEPA Statute and the Council on Environmental Quality (1986). The World Bank, for its part, produced a “user’s guide” by 2003.

In the 21st century, social impact has been mapped and reported by an increasing range and number of firms. For instance, by January 2020, B Labs (a non-profit organisation that provides certification to “good” businesses) has had 50,000 companies use its social impact assessment tool. Private companies report their social impact in an effort to take into consideration and combat issues that were previously deemed public sector concerns, such as environmental degradation, poor labour conditions and gender inequality. Over time, and with the expansion of actors involved in its assessment, the notion of social impact has shifted from the mitigation of negative outcomes to a more active, positive process. The wider business community (particularly with the advent of Michael Porter’s “Shared Value” approach) spoke of the social good that comes from corporate activities, be it for local communities, for employees or the environment.

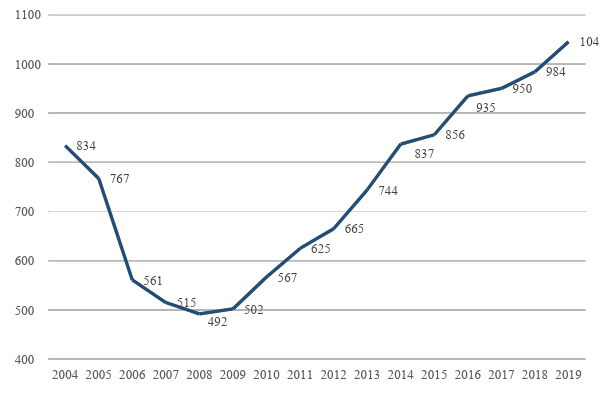

It was at the onset of the global financial crisis that the term found particular salience. According to the Google search term analytics tool, the annual interest in social impact has steadily risen since 2008, with the greatest interest peaking in 2019:

Figure 1: Google Search Term Analytics for “Social Impact”

Source: Author’s analysis of Google Search Term Analytics data (as of December 16, 2019)

In effect, the crisis propelled society’s desire for business activities—and consumer decisions—to deliver positive social and environmental impact. Financial profits were no longer considered the be-all and end-all of capitalism. The economic motor would need to provide society with non-pecuniary and more sustainable outcomes as well. In tandem with changing expectations (of millennials and more), we have seen a deluge of CEOs speak of their commitment to producing both profit and purpose. For instance, in his letter to investors of January 2018, the CEO of Blackrock, Larry Fink, asserted that he was aware that “every company must not only deliver financial performance but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society”. With similar motivation, the Norwegian Pension Fund—the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund with US$1trn in assets—announced in March 2019 that it would divest from oil and gas exploration. Even these large institutional investors commit to investing for social good rather than delivering financial profits; their fiduciary duty, in a way, is increasingly about fuelling social good as well as taking responsible risks in order to deliver financial returns.

Reporting and measuring social impact

With the widespread interest in demonstrating positive social impact, there has been a remarkable proliferation of ways to measure and report it. More than 150 different methodologies have been developed for this purpose (Florman and Klingler-Vidra, 2016). These methods are in addition to the thousands of firms that have each developed their own proprietary approach to conceptualising and measuring impact. Indeed, there are so many different platforms to detail a business’s impact that many now speak of a “reporting burden”.

One of the most important and widely used is the Global Reporting Initiative, an independent entity that launched its first guidelines in 2000. These guidelines (now referred to as “G1”) represented “the first global framework for comprehensive sustainability reporting” and are currently in their 4th iteration. More independent assessment firms entered the space in the years that followed. B Labs offered a reporting and scoring system, after which the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) created the IRIS (impact reporting and investment standards) Metrics in 2009. Since the launch of the SDGs in 2015, these various social impact reporting and certification platforms have incorporated the language and aims of the global goals. What’s more, in late 2018 the Impact Management Project initiated a Structured Network of key stakeholders in an effort to socialise a shared understanding of what social impact is, and how to report it, in an attempt to reduce the alphabet soup in meanings and quell the reporting burden.

Where next?

The juggernaut of efforts to make an impact in the investing and business remits, as well as in local communities, since the global financial crisis is not new. As discussed above, the concept of social impact has been employed—through reporting requirements vis-à-vis real estate development projects—for the past 50 years. Despite the half-century of use, the language of impact remains woolly. It is now evoked in a way which is distinct from its environmental impact assessment origins. Social impact is effectively shorthand for a business’s intention to produce positive outcomes for communities and for the environment through novel products and services. A sort of “impact new deal” has emerged, which assumes that “getting intention right” will reverse the course of capitalism that has seen the denigration of natural resources and manufacturing livelihoods.

I am all in favour of striving for positive social impact, of course. But in the contemporary setting, saying that one’s mission is to boost social impact is like Miss Universe saying that she wants to work to achieve world peace. Just as viewers at home would want to ask the pageant contestant, “okay, but how?”, to avoid impact washing we need to ask those striving for positive impact: “What do you mean by that, exactly? And how will you achieve it? Is what you are now doing really substantively different than what you did before?”

More than that, if we are to talk about delivering a positive impact, we need better mechanisms for giving a voice to those people and places who are being impacted. Instead of businesses producing glossy versions of their annual social impact reports for consumers to download from their websites, I propose a platform where society-at-large engages with businesses to ask questions, share their experience as consumers, local residents, etc. Let’s move towards “crowdsourcing” the measurement of social impact so that the society that is impacted is involved in saying what impact means to them, and how they would perceive genuinely positive advances.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (EIU) or any other member of The Economist Group. The Economist Group (including the EIU) cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this article or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in the article.