Introduction

As the November 2023 Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity Summit concluded, its joint declaration sought to establish "the Americas as the home of the world’s most competitive, inclusive, sustainable, and resilient regional value and supply chains."1 Underpinning this strategic vision are critical minerals, which hold a significant place in global supply chains and inventories due to their essential role in digital and clean energy technology and manufacturing. Latin America stands at the forefront of this shift as the region boasts some of the world's largest critical mineral reserves, uniquely positioning it to contribute to global digital and clean energy transitions.

This article explores the latent opportunity that critical minerals, including rare earth elements, graphite, lithium, and copper, represent for the region. Through an analysis of changing supply and demand dynamics, we ultimately argue that just like fossil fuels once did, critical minerals can represent an unmatched opportunity to drive growth. It also cautions that an over-reliance on this sector comes with economic and political risks.

The gap between critical mineral reserves and their mining and processing

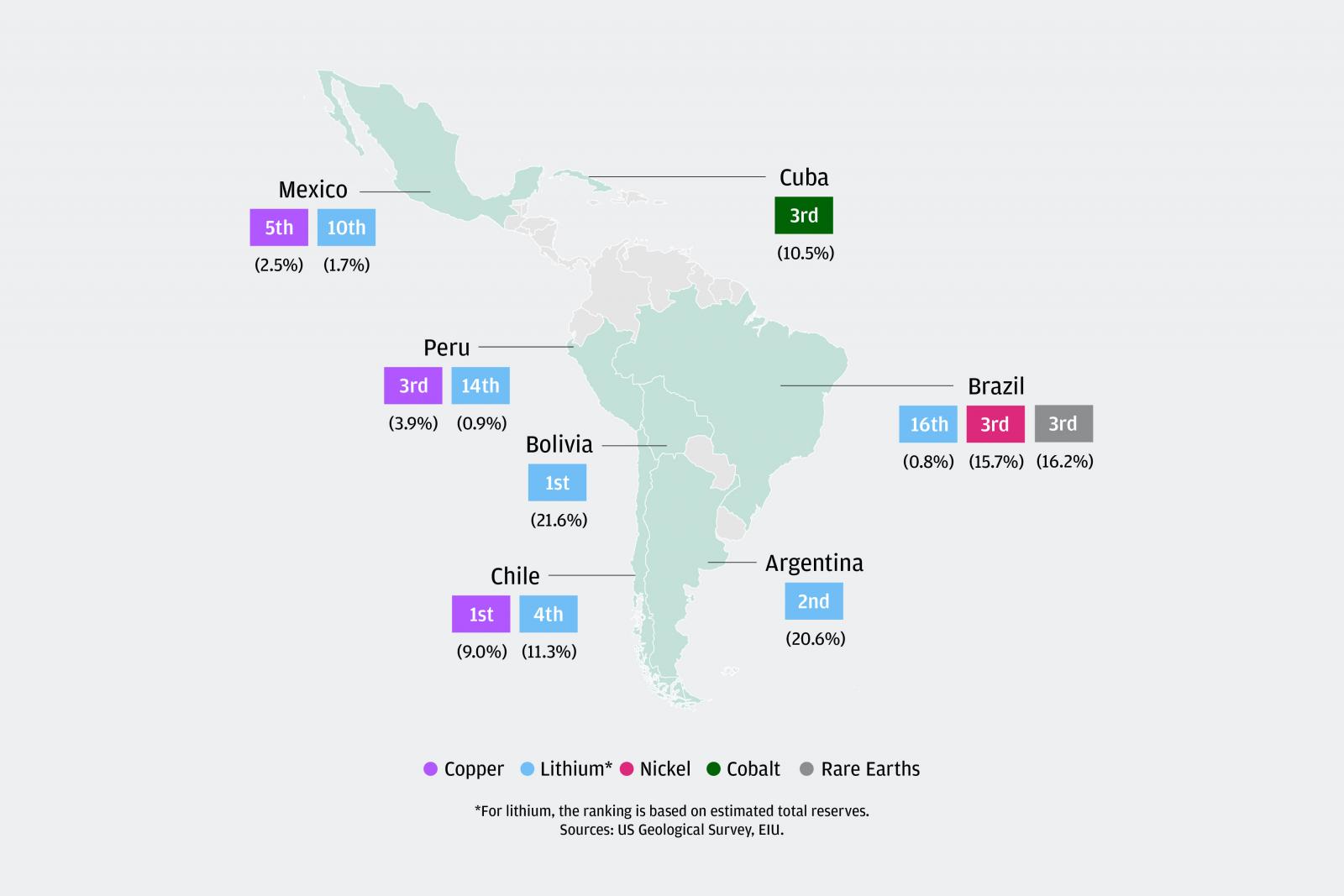

Latin America holds some of the world’s largest mineral deposits, ranging from Chile’s largest and fourth largest deposits of copper and lithium respectively, to Brazil’s third largest global reserves in nickel and rare earth elements (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Latin America’s global critical minerals reserves ranking 2

Source: EIU, 2022

View Info

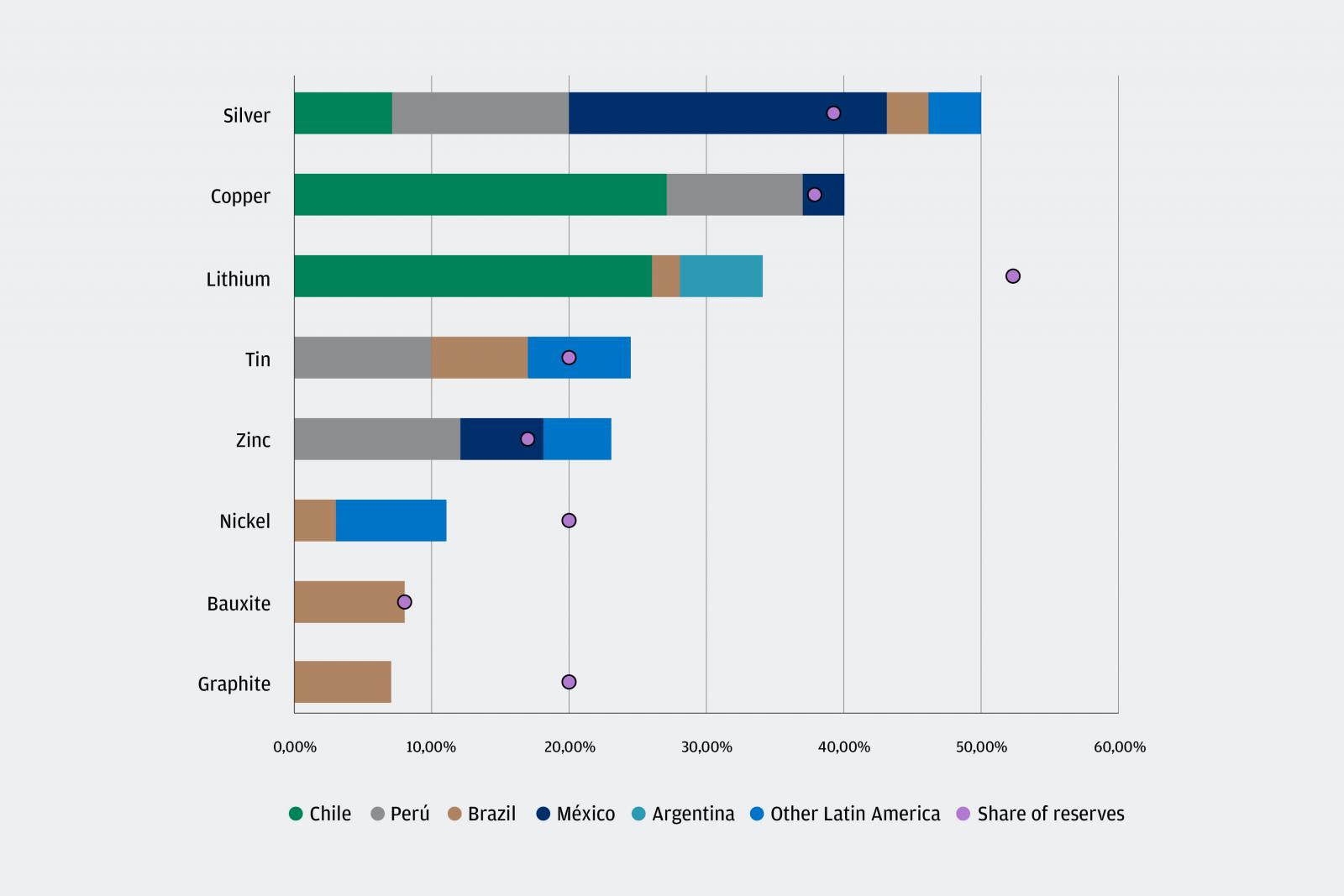

But there are considerable gaps that remain between reserves and actual production (see figure 2). This gap could be attributed to a myriad of factors, including an increasingly complex regulatory environment, lack of critical infrastructure and low extraction and processing capacity to name a few.

Figure 2: Latin America underperforms in its production of critical minerals compared to its vast reserves 3

Source IEA, 2021

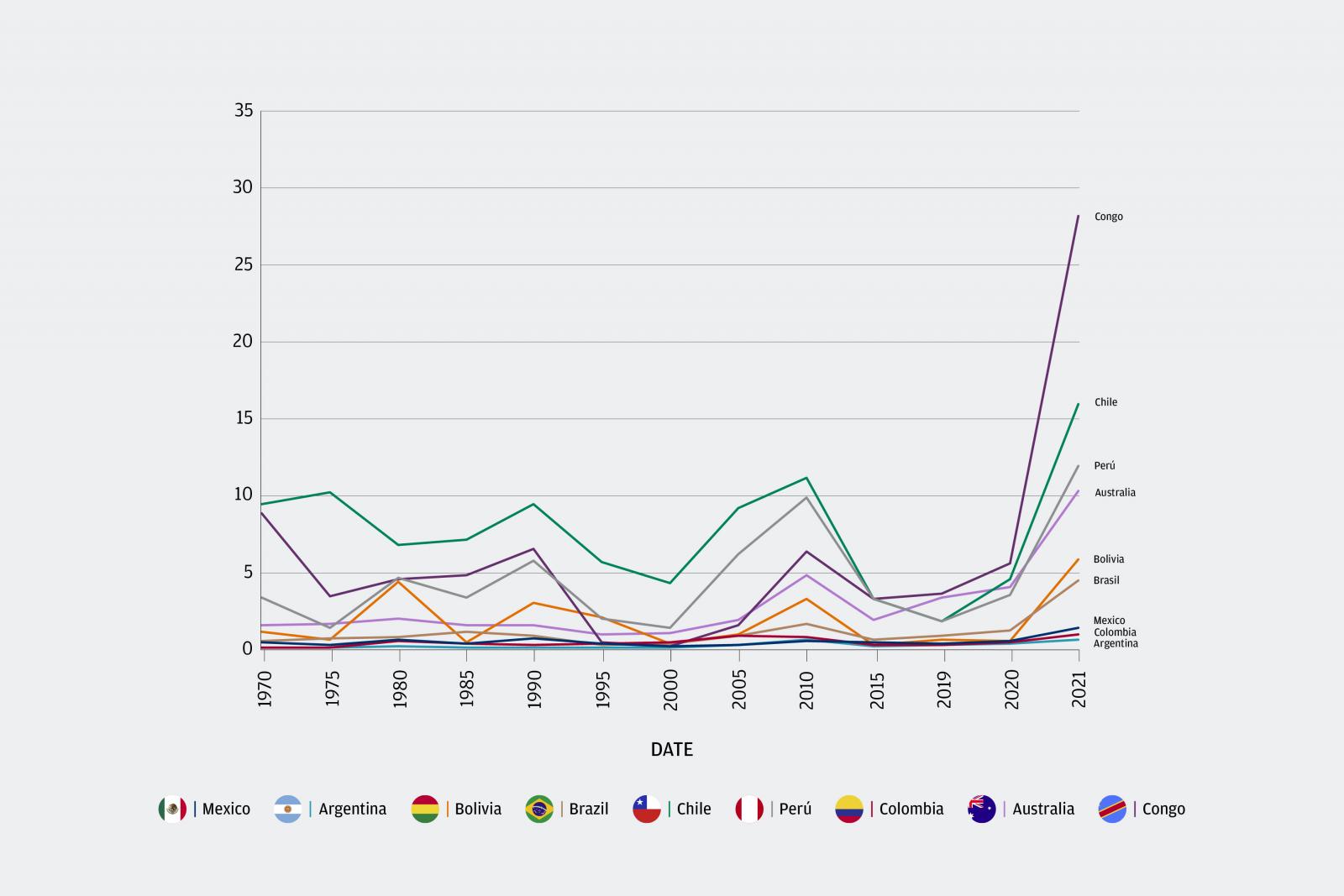

The region, with a few exceptions, has so far not been able to realize its full potential in the value chains for critical minerals, and therefore, in those for clean energy and digital components. Countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo far outpace Latin American countries in terms of mineral rents, or the difference between the value of production for a stock of minerals at world prices and their total costs of production.

Figure 3: Latin America lags behind its competitors in mineral rents 4

Source: World Bank

Investments in Brazil’s rare earth mining industry are ramping up

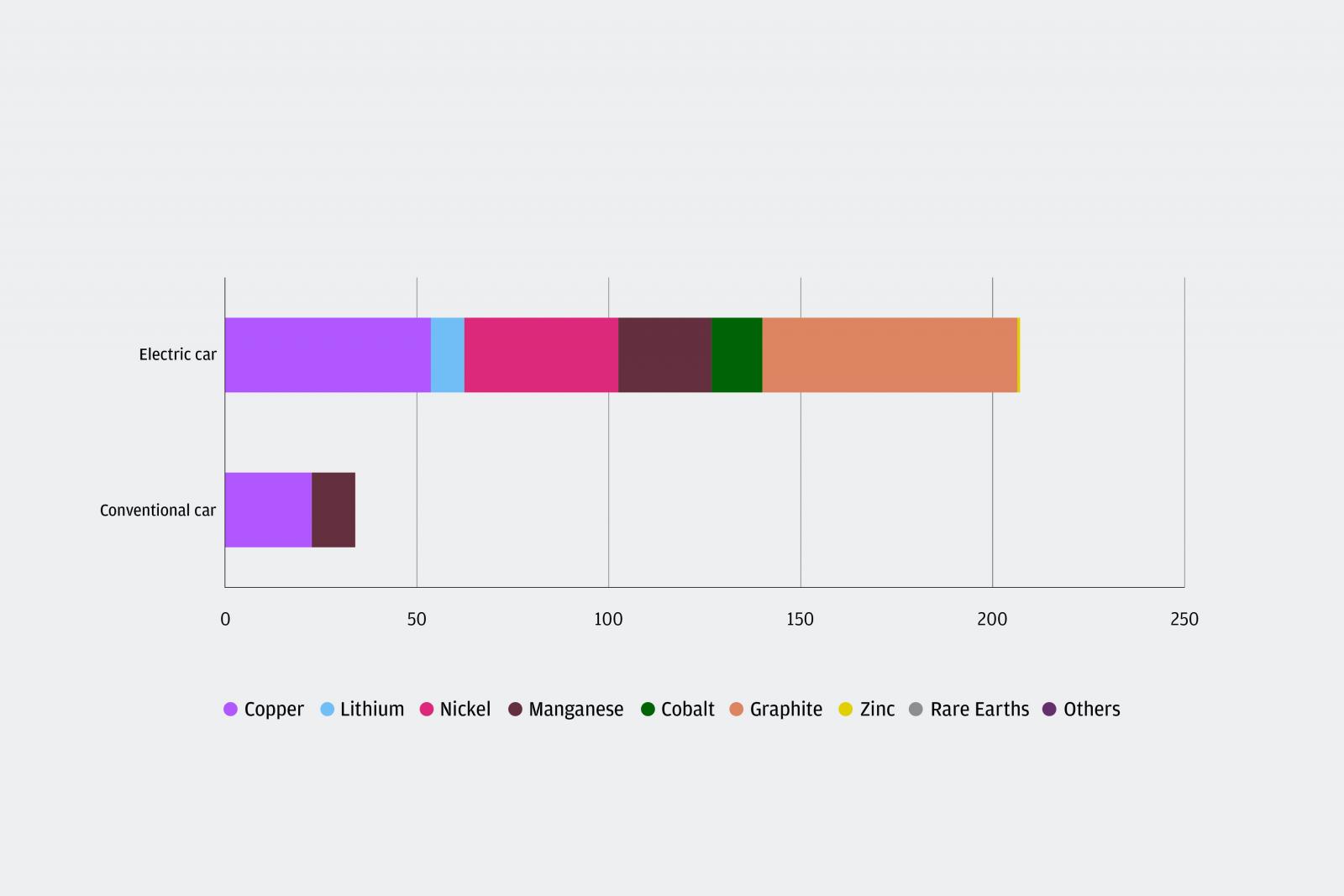

Brazil holds the third largest reserves globally after China and Vietnam<5 for rare earth elements (REE), which comprises a set of 17 metallic elements from the periodic table.6 While REE are often not a large portion of overall product makeup, they are a key component for the functionality of products such as cell phones, flat screen monitors/TVs, electric (EV) and hybrid vehicles, lasers, radar and sonar systems (see figure 4).7 Wood Mackenzie estimates that demand for rare earths will grow to almost 240,000 tons by 2030, up from 171,300 in 2022.8

Figure 4: Critical minerals used in EVs compared to conventional vehicles 9

Source: IEA, 2021

Although Brazil has classified REEs as “strategic minerals” as part of its 2030 National Mining Plan, there is currently no operator who extracts REE concentrates separately from other elements, thus they have not yet been commercialized.10 This is poised to change. In 2023, Brazilian mining company Mineração Serra Verde announced a $170 million investment that, when completed, will produce a unique mineral concentrate from four REEs that are essential for use in EV motors and wind turbine generators.11 Brazil stands to become the third-largest producer globally, and the first outside Asia to produce these REEs. Brazil is currently the third-largest global producer of graphite, which is widely used in batteries. As China tightens export controls on graphite, it presents a unique opportunity for Brazil to bolster its mining and production capacity and nearshore supply chains.12

Changing regulations and tax regimes are altering the status-quo

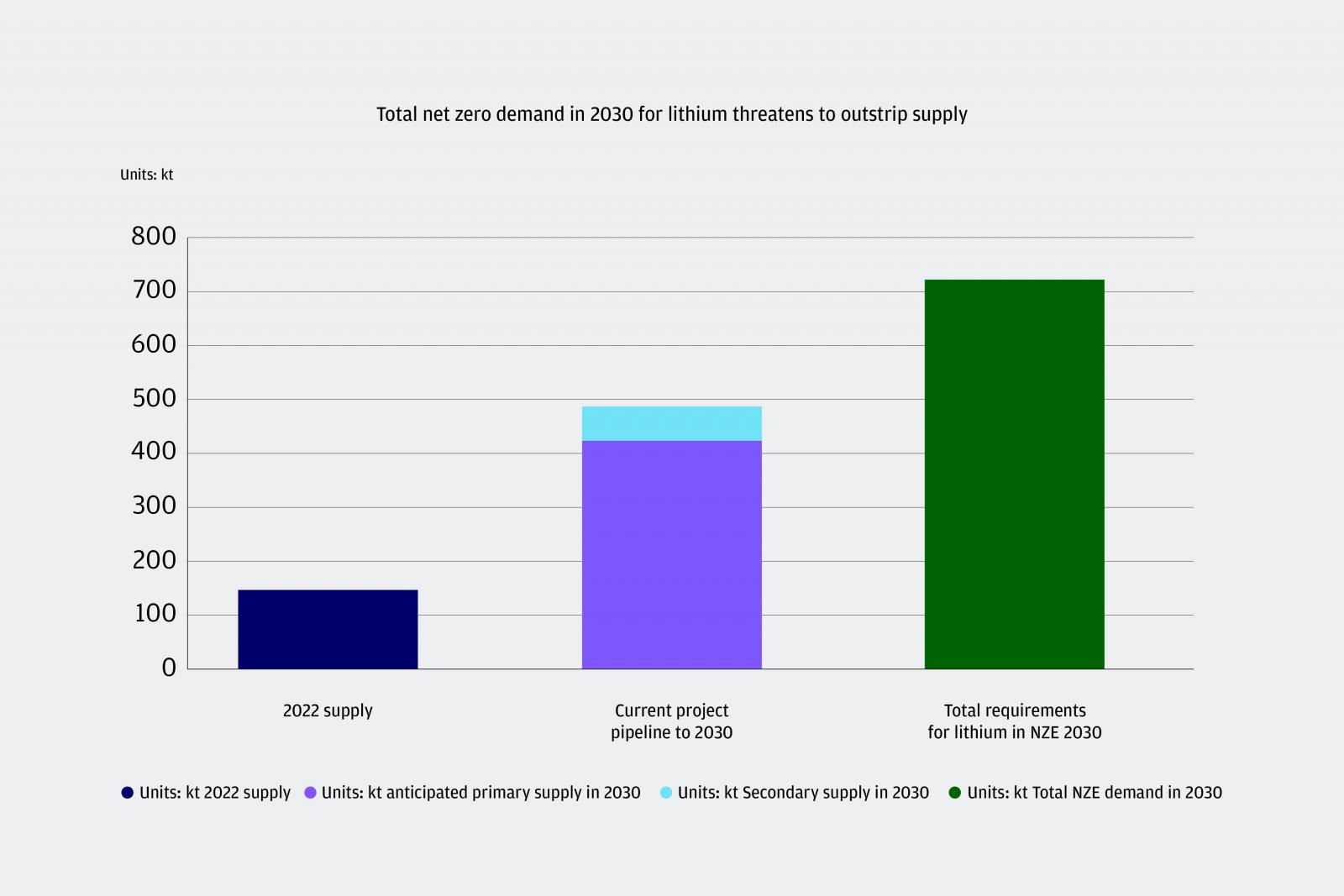

Lithium is a catalyst of the green energy transition as well as digital transformation based on its presence in rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. These can be used in anything from EVs, to laptops, to solar power backup storage.13 As such, demand for lithium to achieve net zero goals could far outstrip supply as soon as 2030 (see: figure 5). The region’s lithium-rich salt flats located in the "lithium triangle," comprising Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia, collectively hold more than 50% of the world's known lithium reserves.14 However, changes to lithium mining regulations are underway in the region.

Figure 5: Total net zero demandin 2030 for lithium threatens to outstrip supply 15

Source: IEA

Mexico has enacted a new decree declaring lithium as a national resource of public utility, banning private companies from exploring and exploiting lithium; all such activities will be carried out by a decentralized public authority, created by the Mexican government, “LitioMx”.16 This has created hurdles for current projects, including the Sonora mine that Chinese producer Ganfeng Lithium bought for $356.8mn in 2021 and was expected to be in production by 2023.17 The Bolivian lithium industry was nationalized in 2009 as the country declared it as a “strategic element.”18 Lithium mining is currently managed by the state-run Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB), however, its output from a pilot project only amounted to 600 tons of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE) in 2022.119 Although President Luis Arce has signed two agreements with Russian and Chinese companies in 2023, they are unable to be finalized as there is currently no legal framework to determine how foreign companies can extract or industrialize lithium in the country.20 Bolivian lawmakers are currently debating several pieces of legislation to determine mining royalties, ranging from a minimum of 3% to a maximum of 20%.21

Reconciling existing mining practices with inclusivity will impact future opportunities

Latin America accounts for 40% of global production of copper, owing to strong reserves and mining capacity in Chile, Peru, and Mexico among others in the region.22 Copper wiring is a key component of technology including 5G networks and Internet of Things devices, EVs, charging infrastructure, and solar photovoltaics, among other clean energy technologies.23, 24 The central role of copper in the green transition means that its demand could accelerate strongly in 2025 and beyond, which represents an opportunity to bolster investment in mining and processing this strategic element.25

Recently, the region's copper mining industry has clashed with the movement for inclusive growth, which aims to address the needs of long-ignored local and indigenous communities and the environment in existing and new business opportunities. “Given previous experiences with the extractive industry, there has been a movement of civil society and specific groups that are more cautious about the benefits of extractive industries and particularly mining can have on the well-being of its citizens which has in turn affected the development of regulations and discussions of what is the future of mining in the region,” says Maria Fernanda Ballesteros is Mexico country manager at Natural Resource Governance Institute.

In fall 2023, Panama erupted in several weeks of protests over a copper mining contract awarded to a Canadian company that was deemed corrupt and harmful to the environment. Panama, which holds 1.5% of global copper reserves, stood to lose an annual GDP growth of 6% if this mine closed. The mine has been temporarily closed for maintenance as supplies to keep the mine running have been blockaded.26 Peru, which holds the 3rd largest deposits of copper globally is experiencing similar domestic turmoil: mining investors must anticipate the risk of social unrest as protests by rural communities against mining operations are becoming increasingly violent and are causing lengthy disruptions to operations.27

Mexico, which holds the 9th largest copper reserves globally, has started to take formal steps to bolster inclusivity and domestic protectionism within the mining industry. The Mexican Senate approved mining industry reforms, including a requirement for mining companies to pay 5% of their profits to local communities, and reduction in the maximum length of concessions from 50 to 30 years.28

Diversification of supply chains is needed to meet both demand and energy security needs

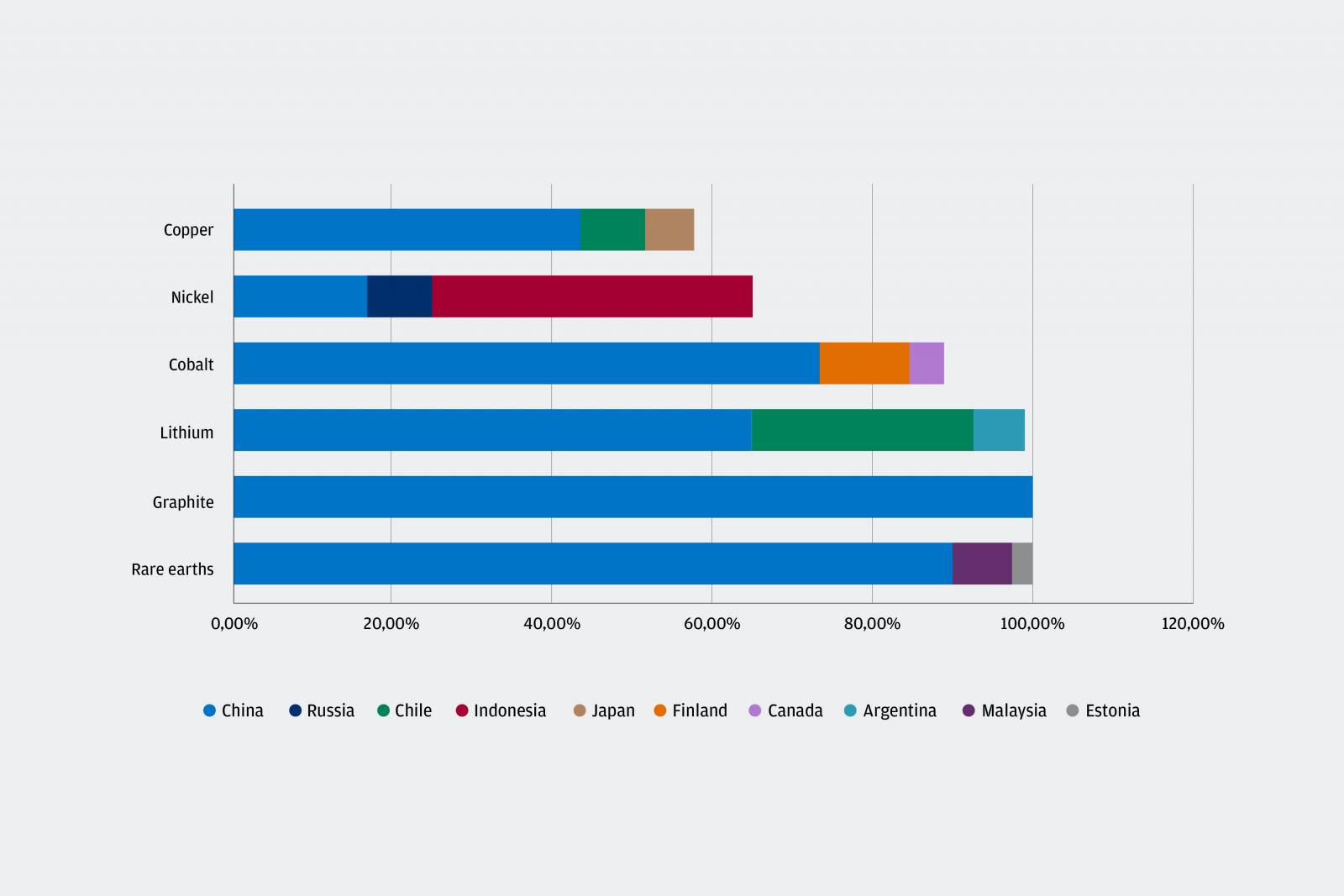

As the region navigates self-imposed regulatory hurdles, reserves remain untouched. At the same time, a dual challenge has emerged: critical mineral supply chains, including mining but especially processing, are increasingly controlled by one source, China (see figure 6), while at the same time global demand for critical minerals continues to increase.

Figure 6: Despite Latin America holding some of the largest critical mineral reserves, China dominates processing, 2022 29

Source: IEA, July 2023

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has expressed cautious optimism that the recent boom in investments in critical minerals will help meet increasing demand to achieve net-zero transition targets. But it warns both project delays and cost overruns continue to pose risks, and only “limited progress” has been made on supply sources for critical minerals; in terms of refining/processing, the market share of countries like China has increased.30

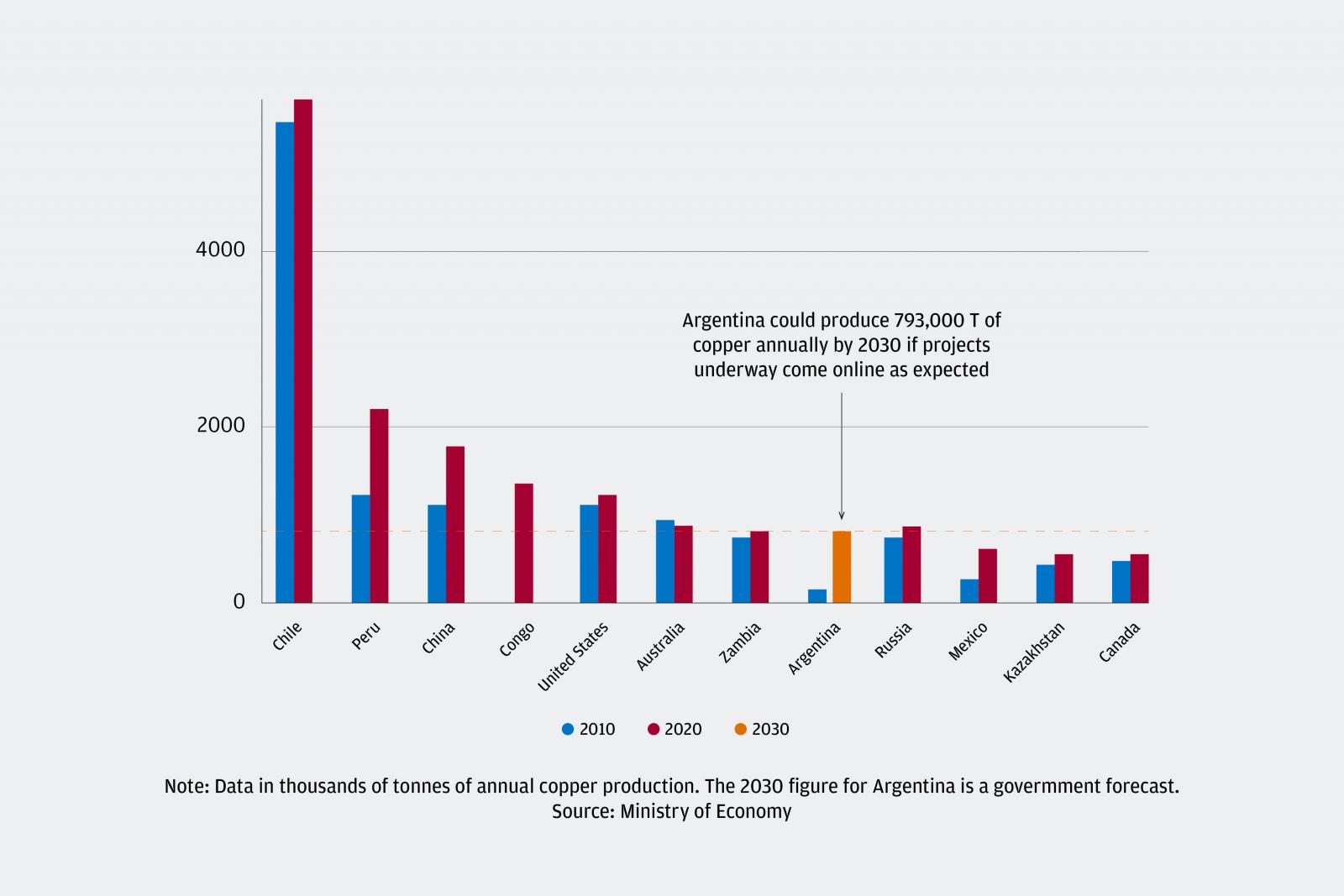

Other forecasts paint a gloomier picture. Examining the current copper market, demand of the element for the energy transition is expected to double by 2035, but copper supply shortfalls begin in 2025 and last throughout the decade.31 To bridge this gap, the world will need to increase copper supply rapidly. While there is a general consensus that Latin America cannot completely satisfy global copper demand, almost $50USD billion is being invested in copper projects in the region that will begin production before 2030, adding 3.2 Mt/y to the current 7.6Mt/y.32 Argentina, which currently produces no copper, has six projects in the pipeline that are expected to come online before 2030, and could produce 793,000 tons/year, putting Argentina amongst the top 10 global copper producers worldwide (see Figure 7).33

Figure 7: Thousands of tonnes of annual copper production. Argentina’s forecasted copper production sets it into the top 10 globally 34

Source: Reuters Graphics

Conclusion

For Latin America, capitalizing on its vast critical mineral reserves is worth consideration. As the region attempts to reconcile its murky past with the mining industry, sometimes creating bottlenecks to domestic and foreign investment, commodity prices are keeping pace with rising demand for critical minerals to meet targets in the clean energy and digital transitions, increasing the value in critical mineral mining and processing investments. Australia, despite having half the amount of lithium reserves as Chile, managed to become the largest lithium producer, according to data from the US Geological survey from 2021.35 The country has created a Critical Minerals Strategy that has invested $4AUS billion in various mining and processing operations.36 If the region followed suit, it could establish itself as a key player in the global upstream and midstream critical mineral supply chains, which would create ripple effects on near-and re-shoring opportunities in other sectors as well.

1 https://www.voanews.com/a/biden-to-meet-latin-leaders-on-economics-migration/7340333.html

2 https://viewpoint.eiu.com/analysis/article/993662482/

3 https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/latin-america-s-share-in-the-production-and-reserves-of-selected-minerals-2021

4 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MINR.RT.ZS?locations=BR-AR-CO-BO-PE-CL-MX-AU-CD

5 https://www.vinachem.com.vn/content/market-and-product-vnc/rare-earths-reserves-top-8-countries.html

6 https://www.americangeosciences.org/critical-issues/faq/what-are-rare-earth-elements-and-why-are-they-important

7 https://www.energy.gov/fecm/rare-earth-elements

8 https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-u-s-wants-a-rare-earths-supply-chain-heres-why-it-wont-come-easily-dfc3b632

9 https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/minerals-used-in-electric-cars-compared-to-conventional-cars

10 https://www.agp.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/planoNacionalMinera.pdf

11 https://www.brasilmineral.com.br/noticias/com-a-serra-verde-goias-ingressa-no-mercado-mundial-de-terras-raras

12 https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/06/opinion/electric-battery-energy-china.html

13 https://dec.vermont.gov/sites/dec/files/wmp/SolidWaste/Documents/lithium-basedBatteryManagementFactSheet.pdf

14 https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/10/17/lithium-triangle-mining-prices-electric-batteries-south-america-economy/

15 https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/anticipated-supply-and-projected-demand-for-lithium-in-the-net-zero-scenario-2030

16 https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-policy-monitor/measures/3941/reserves-all-lithium-exploration-and-exploitation-activities-exclusively-for-the-mexican-state

17 https://www.ft.com/content/5424e057-e0bf-42eb-907e-af63683452a9

18 https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/articles/2023/november/28/investing-in-lithium-in-bolivia#:~:text=Lithium's%20Legal%20Regime%20in%20Bolivia&text=However%2C%20this%20general%20mining%20framework,be%20carried%20out%20by%20YLB%E2%80%9D.

19 https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/latin-americas-lithium-sands-are-shifting/

20 https://english.elpais.com/economy-and-business/2023-05-12/from-a-meeting-with-stiglitz-to-tensions-with-the-us-luis-arce-changes-the-course-of-lithium-politics-in-bolivia.html

21 https://www.bnamericas.com/en/news/bolivia-seeks-consensus-on-lithium-royalties

22 https://www.iea.org/commentaries/latin-america-s-opportunity-in-critical-minerals-for-the-clean-energy-transition

23 https://www.dnv.com/article/the-role-of-copper-in-the-energy-transition-247342#:~:text=Infrastructure%20(incl.,cities%20require%20lots%20of%20copper.&text=More%205G%20networks%3B%20Internet%20of,for%20efficient%20connectivity%20and%20conductivity.

24 https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/research-analysis/growing-appetite-copper-threatens-energy-transition-climate.html

25 https://viewpoint.eiu.com/analysis/article/443594427

26 https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/first-quantum-place-panama-copper-mine-maintenance-mode-sources-2023-11-20/

27 https://viewpoint.eiu.com/analysis/article/503481433

28 https://apnews.com/article/mexico-mining-reform-concessions-payments-laws-e039d83fbe72a90e1d2729d492cff2c5

29 https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/share-of-top-three-producing-countries-in-processing-of-selected-minerals-2022

30 https://www.iea.org/reports/critical-minerals-market-review-2023/implications#abstract

31 https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/research-analysis/growing-appetite-copper-threatens-energy-transition-climate.html

32 https://www.bnamericas.com/en/features/latin-americas-copper-projects-seen-as-insufficient-to-avoid-a-deficit

33 https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/red-metal-rising-argentina-sets-lofty-sights-global-copper-top-10-2023-05-08/

34 ibid

35 https://www.mining-technology.com/features/critical-mineral-geopolitics-latin-americas-untapped-potential/

36 https://exportfinancecdn.azureedge.net/media/pdajuigc/critical-minerals-brochure_oct23.pdf