Nigeria has seen a steady increase in the prevalence of viral hepatitis over the past few decades. The introduction of a routine immunisation programme in 2004 for hepatitis B contributed to a drop in the overall rate of hepatitis infection in children; the number of cases in adults continues to rise.1

The Nigeria HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey (NAIIS) in 2018 estimates that the overall prevalence of hepatitis B (HBV) is 8.1% and 1.1% for hepatitis C (HCV). This means that an estimated 19 million Nigerians are living with HBV or HCV.2

Hepatitis B and C are particularly deadly forms of the virus, as they can cause chronic illnesses leading to liver cirrhosis and cancer. Since HIV, HBV and HCV are all transmitted through blood and other body fluids, people are often “co-infected” with more than one of these infections. Co-infection rates remain a cause for concern, with the NAIIS survey revealing rates of 9.6% and 1.1% for HIV/HBV and HIV/ HCV co-infections respectively in people living with HIV.3

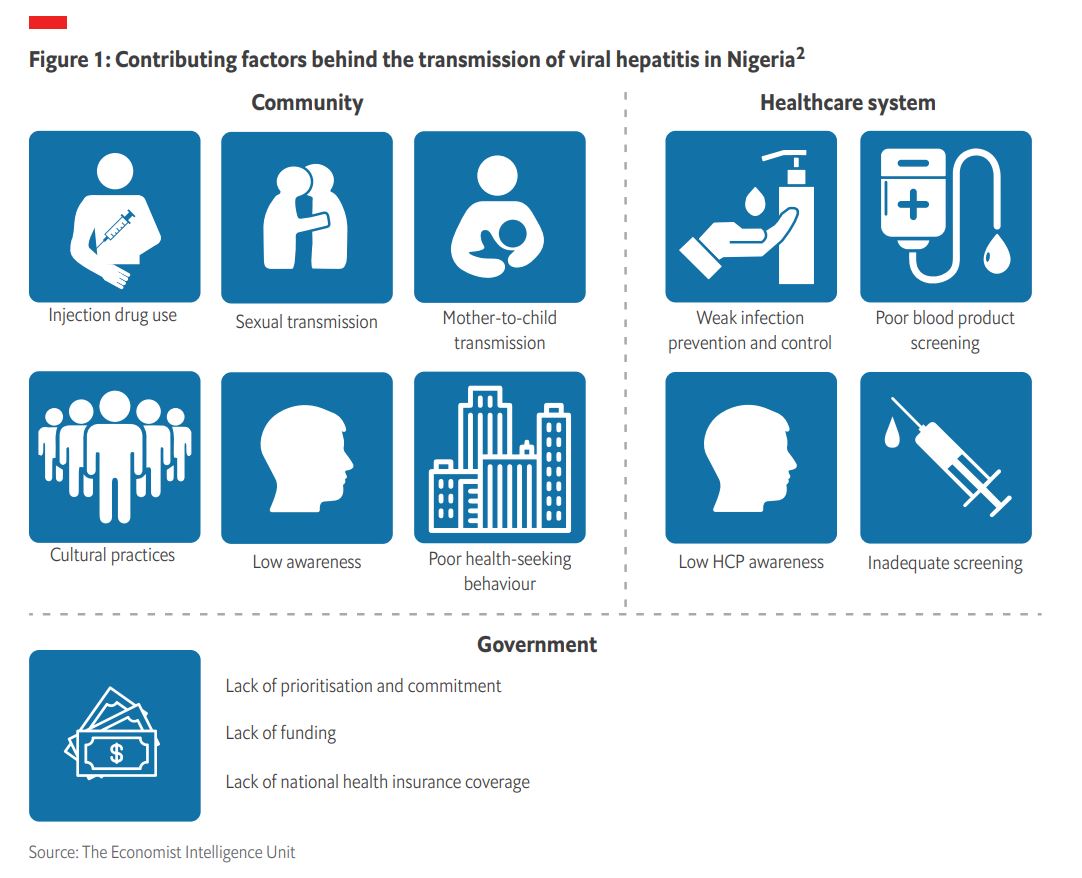

However, Dr Ruth Bello, Consultant Hepatologist in Nasarawa State highlights that the burden in rural and marginalised Nigerian communities has been found to be higher than the national average. She says that over the last three years in Nasarawa State, the prevalence of HBV and HCV was reported to be 10% and 13.2% respectively, Figure 1 summarises the key factors contributing to the transmission of viral hepatitis in Nigeria, across community, healthcare system and government factors.

Low levels of health awareness and poor-health seeking behaviours are key drivers

Both HBV and HCV infections are preventable through the avoidance of risk factors. For HBV, although there is currently no cure, a vaccine is available. Mother-to-child (or vertical) transmission is one of the main routes of infection, accounting for 90-95% of chronic childhood HBV infection that persists into adulthood.4 Despite free HBV vaccination being available via the routine childhood immunisation programme in Nigeria, the uptake remains poor, with vaccine coverage estimated to be around 51%.2 Dr David Uzochukwu, a general practitioner specialising in hepatitis diagnosis and treatment, attributes this partly to poor health knowledge with individuals against vaccination as a practice. Dr Danjuma Adda, Founder of Chagro Care Trust and patient advocate agrees, explaining that the poor uptake rate is especially noticeable in more rural and socio-economically deprived areas, where culture and religion have a strong influence, and individuals often seek medical advice from alternative medical practitioners and herbalists.

Apart from vaccination, screening is vital to find how many people in the country are living with either an HBV or HCV infection, and to link them to the right care. On World Hepatitis Day 2020, the World Hepatitis Alliance chose the theme “find the missing millions” to highlight those people who remain undiagnosed and therefore untreated. The nature of the infections means that HBV and HCV are usually asymptomatic and can go unnoticed until individuals’ livers are significantly damaged. Often described as Nigeria’s silent killer, figures show that more than half the population is likely to have never been tested.8 Poor health-seeking behaviours are a major challenge that makes screening for viral hepatitis difficult in Nigeria. Similarly, most Nigerians do not attend annual medical checks where there is the opportunity for infections to be detected early. In parts of northern Nigeria where there are areas dealing with conflict, this further impacts the success of advocacy, screening and immunisation programmes.5 Organisations such as the Society of Family Health (SFH) in Nigeria recognise the importance of bringing health closer to individuals and their homes to improve access to, and uptake of, essential health information and services. For example, SFH supports the Nigerian government with service delivery by utilising primary health care facilities and social franchising networks comprising private and faith-based hospitals.6

“Decentralisation of care and taskshifting to non-specialists is one way in which the management of hepatitis could be rapidly improved in Nigeria.” Dr Ruth Bello

Furthermore, gaps in knowledge around infection prevention and control, and safe needle exchange among health professionals needs to be addressed across the country. At present, the majority of hepatitis expertise is concentrated within highly specialised health facilities (tertiary care).2 Dr Uzochukwu concurs, outlining that in 2016, there were approximately 108 hepatitis specialists in Nigeria, all of whom were practicing in the major cities. This shortage of experts and the resulting geographic barrier to access is problematic, as many general practitioners working in primary care are not well trained in how to diagnose HBV or HCV, which laboratory tests are required and which treatments to administer. There is also lack of awareness on modes of transmission among health workers, with a study finding that only 44% of health workers were aware that HBV could pass between mother and child.7 All healthcare workers should receive ongoing training and education on the routes of hepatitis transmission and diagnosis and treatment options.8

Awareness about the disease is also low because the Nigerian government has not placed enough focus on partnering with non-governmental organisations and donor agencies that concentrate solely on advocating for hepatitis elimination. Traditionally, the focus has been on treating diseases such as HIV and TB, which has left the hepatitis programme in the country underfunded.9 With undiagnosed hepatitis being such a critical problem in Nigeria, it is imperative that more initiatives and campaigns to raise awareness on viral hepatitis are launched.

Addressing funding issues surrounding hepatitis screening, diagnosis and treatment

Besides improving levels of knowledge on viral hepatitis in Nigeria, the gaps in funding for screening, diagnosis and treatment are probably the most critical issues to address.

Dr Uzochukwu says that with the help of civil society organisations, donors and advocates, free screening camps for HBV and HCV have been made available in some parts of the country. However, these are not geographically accessible by everyone who needs them, and the Nigerian Government is yet to fund the camps on a large-scale basis. Moreover, even though some free hepatitis screening programmes are available for pregnant women, there is no funding available to provide vaccinations and prevent infection in those mothers who test negative. In the same way, there are no affordable HBV vaccination schemes in place for at-risk populations including healthcare workers, people who inject drugs and men who have sex with men.2 Nevertheless, the national hepatitis clinical guidelines recommend that at-risk populations such as healthcare professionals and key workers be screened for hepatitis infection.4

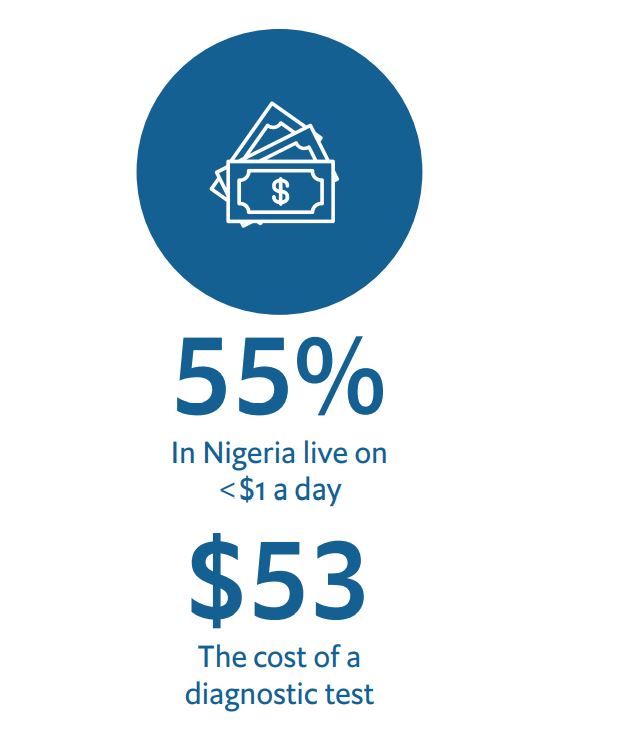

Despite a significant push to implement universal health coverage in Nigeria, approximately 95% of the population is still not covered by the National Health Insurance Scheme.2, 8 In addition to this, the 2016 National Guidelines for the Prevention, Care and Treatment of Viral Hepatitis focus on the inclusion of viral hepatitis as part of the universal health coverage, however, this is yet to happen.4 Since the cost of vaccines, testing and treatment must be paid for privately, this significantly hampers uptake. Dr Danjuma Adda comments that with 55% of Nigerians living on less than 1 USD a day, hepatitis screening, diagnosis and treatment is beyond the reach of most citizens. He estimates that of the 19 million individuals predicted to be living with viral hepatitis, less than 5% can afford to be tested. This is not too surprising, given that a viral load test for hepatitis costs 20,000 Naira (53 USD) and the 12-week treatment course for curing a chronic HCV infection costs between approximately 200 to 300 USD.9 Moreover, Dr. Adda says that a significant amount of the rapid test kits being used in primary and secondary care are not prequalified by the World Health Organization, making them unreliable. The better-quality testing equipment such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and molecular platforms for viral load, are generally only available in tertiary care settings. To add to the problem, these are often in limited supply. According to Dr Adda and Dr Uzochukwu, the substantial accessibility issues force individuals to turn to herbalists for alternative treatments, which often worsens their condition.

Over the years, the Nigerian government along with Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology has been partnering with donor organisations to come up with ways to make hepatitis care more affordable and accessible in the country, but more financing is required.8

Nasarawa State takes matters into its own hands

As a whole, the country has been slow to fully implement its strategies, which has spurred responses at the State level to scale testing and treatment. Nasarawa is leading in these efforts and serves as a valuable case study. In 2015, the State government launched their initial viral hepatitis elimination program and in February 2020, announced its 5-year HCV elimination plan. The plan aims to screen over 2.4 million individuals and treat 124,000 by 2024, six years ahead of the WHO’s 2030 target.10

Dr Ruth Bello, who is a member of the Viral Hepatitis Technical Working Group in Nasarawa, says that the State government has improved hepatitis services by shifting tasks where possible. Task-shifting and strengthening of hospital and specialist health services across the state has stimulated increased awareness and demand for viral hepatitis services. Despite the effect of the covid-19 pandemic on the resilience of the Nigerian health system, the Nasarawa State government has proceeded to build the capacity of healthcare workers across 21 health facilities to improve hepatitis care. Through the commitment of a seed fund of 40 million Naira (110, 000 USD), Nasarawa has screened over 85,000 people and cured 1,300 of those who were found to be infected.9

Looking forward to 2030 and the need for more commitment

With 2030 coming up fast and considering the impact of the covid-19 pandemic on health systems around the globe, Nigeria will need to quickly gain momentum on its efforts towards elimination of viral hepatitis if it is to going to reach the WHO target. The country has what it takes to achieve this goal in terms of the plans, strategies and guidelines that it already has in place. However, further political and financial commitment by the Nigerian government is needed to implement these policies.

Looking ahead, the Ministry of Health should prioritise partnerships with donor organisations to fund the expansion of the National Health Insurance Scheme to cover all aspects of hepatitis care. National-level price negotiations for viral hepatitis testing and treatments could further support this expansion of access. Hepatitis awareness campaigns for the general public and healthcare professionals are also important to increase health literacy and improve health-seeking behaviour. Additionally, healthcare professionals require training to raise awareness of and knowledge about viral hepatitis. Central government could also seek to learn from best practice examples within the country to improve services.

While every effort has been taken to verify the accuracy of this information, The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this report or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in this report. The findings and views expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsor.

[1] Nwokediuko S. Chronic Hepatitis B: Management Challenges in Resource-Poor Countries. Hepatitis Monthly [Internet]. 2011;11(10):786-793. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3234575/

[2] The Journey to Hepatitis Elimination in Nigeria - Hepatitis B Foundation [Internet]. Hepatitis B Foundation. 2020 Available from: https://www.hepb.org/blog/journey-hepatitis-elimination-nigeria/

[3] World Hepatitis Day: Nigerians implored to be screened and vaccinated - Nigeria [Internet]. WHO. 2019 Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/world-hepatitis-day-nigerians-implored-be-screened-and-vaccinated?country=979&name=Nigeria

[4] Why Nigeria must find everyone who has hepatitis and doesn’t know it [Internet]. The Conversation. 2020. Available from: https://theconversation.com/why-nigeria-must-find-everyone-who-has-hepatitis-and-doesnt-know-it-143208

[5] Dying Unaware: Race to rescue “the missing millions” from hepatitis in Nigeria [Internet]. Nigeria Health Watch. 2019. Available from: https:// nigeriahealthwatch.medium.com/dying-unaware-race-to-rescue-the-missing-millions-from-hepatitis-in-nigeria-98b80b07b1be

[6] Health and Social Systems Strengthening. Society for Family Health, Nigeria. 2020. Available from: https://www.sfhnigeria.org/health-and-socialsystems-strengthening/

[7] Kolawole, Akande & Akere, Adegboyega & Osundina, Morenike. (2018). Knowledge of hepatitis B virus and vaccination uptake among hospital workers in south west, Nigeria.

[8] Enabulele O. Achieving Universal Health Coverage in Nigeria: Moving Beyond Annual Celebrations to Concrete Address of the Challenges. World Medical & Health Policy. 2020;12(1):47-59.

[9] Folorunsho-Francis A. At N20,000, hepatitis test is beyond most Nigerians -Investigation - Healthwise [Internet]. Healthwise. 2020. Available from: https://healthwise.punchng.com/at-n20000-hepatitis-test-is-beyond-most-nigerians-investigation/

[10] Nasarawa Budgets N40m To Combat Hepatitis. Hepatitis Voices. 2020 Available from: https://hepvoices.org/2020/02/nasarawa-budgets-n40m-tocombat-hepatitis/