“In its original form the modest fashion industry was a grassroots movement borne out of a growing generation of young Muslim women wanting to assert their Muslim identity,” says Shelina Janmohamed, vice-president of Ogilvy Islamic Marketing (an arm of the creative ad agency Ogilvy). Since then the sector has expanded beyond traditional elements such as the hijab to include loose-fitting and less revealing clothing.

When “modest fashion” was emerging as a distinct category, designer and entrepreneur Rabia Zargarpur was among those who helped coin the term. “I insisted that it should be called ‘modest fashion’ to be more inclusive rather than ‘Islamic fashion’,” she says. “I see [the sector] addressing professional women and body-conscious women too.”

Her search for modest clothing in US malls in the early 2000s yielded little success. “Fun shopping experiences became depressing because I couldn’t find anything to wear,” she recalls.

But with a degree from a New York fashion college and a stint at luxury fashion house Valentino under her belt, Ms Zargarpur decided to chart her own course. In late 2001 she founded the label Rabia Z with a line of ready-to-wear turbans, long shirt-dresses, and contemporary tunics. Today it is one of the best-known brands in a growing modest fashion sector.

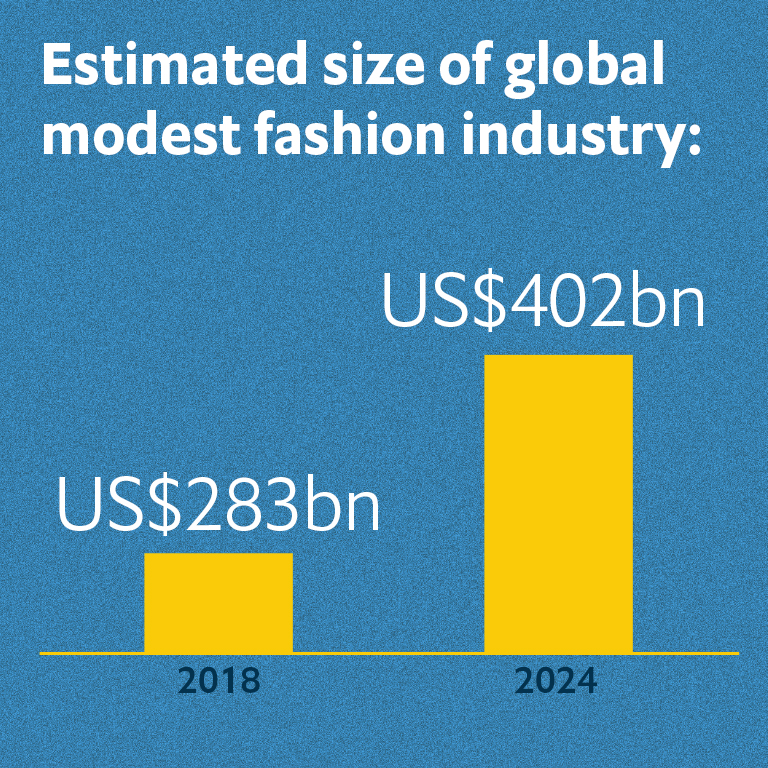

Western labels are now trying to win a slice of the market. In 2018 the global modest fashion industry was worth US$283bn—a figure that is expected to balloon to US$402bn by 2024.[1] That growth is spurred primarily by 1.8bn Muslims who, by 2050, will account for 31% of the world’s population.[2] Two-thirds of all Muslims are under the age of 30 [3], making them the world’s youngest consumer segment.[4]

This cohort has long complained that retailers do little to engage with them, but that is slowly changing. High-street brands such as Mango and Uniqlo have recently launched Ramadan collections, as have luxury labels such as Dolce & Gabbana and DKNY. The high-end online retailer Net-a-Porter runs an annual “modest edit” featuring exclusive designs from the likes of Oscar de la Renta, Jenny Packham and Dubai-based SemSem.[5] Sporting brands Nike and Adidas have also entered the fray, with both now offering a sports hijab.[6]

Magazines and catwalks are growing more inclusive too. In 2017 Halima Aden, an American of Somali descent, became the first hijabi woman to make the cover of Vogue while an H&M campaign last year featured its first hijab-wearing model, Mariah Idrissi.[7] In addition, hijabi models are increasingly sought after to walk the runways of mainstream global fashion shows.

Powering digital growth

The positive response to modest fashion has surprised many mainstream designers, says Reina Lewis, a professor of cultural studies at London College of Fashion. “I don’t think brands had anticipated the sort of uptake they got,” she suggests. “Any time a model appeared in a hijab in an online campaign it went viral within seconds. So it has become very clear to brands that there's a huge appetite among religious consumers to feel seen.”

Brands are responding by enlisting Islamic influencers who use social media to teach their followers how to compile modest looks. Meanwhile, a growing number of modest e-retailers are enabling these brands to reach shoppers across the world.

Kerim Ture, founder of one such website, Modanisa, says it was hard to convince local modest designers to sign up when he first launched in Istanbul in 2011. Today the site stocks more than 850 labels from small boutiques to big international brands and connects them to customers across 135 countries.[8]

“Some of these guys had literally two or three machines” before they joined Modanisa, Mr Ture recalls. “They didn’t have an outlet to go to because they were producing only for their neighbourhood.” Some have since grown into factories of 200 or more machines, he says, and “are reaching out to the world”.

Mr Ture believes his company is on its way to becoming one of Turkey’s first unicorns, a company valued over US$1bn. But “this isn't just about selling clothes,” he insists. “It’s about a woman’s right to go to the prom night or feel comfortable in a corporate environment. It’s not selling a modest swimsuit; it’s giving them the sea to enjoy. It’s about enabling women to expand their reach without compromising their values and beliefs.”

Navigating the market

That is not to say the industry is immune to the challenges facing other retailers. The Modist—a Dubai-based competitor of Modanisa—closed its digital doors in April, citing the coronavirus pandemic as the cause. Modest brands and retailers face funding issues as awareness among investors of this niche industry and its potential remains low. “I think that they just want to see more traction in our industry,” explains Ms Zargarpur. Big brands that have tested the waters must share their experience of both success and failure.

Indeed, Western labels have encountered problems. When the US retailer Banana Republic started selling hijabs last year it was criticised for using campaign images featuring models in short sleeves.[9] The UK’s Marks & Spencer enraged some customers when it launched a “modest” section of its website in 2018: critics said they resented the inference that they were immodestly attired.[10]

Among international brands, Ms Janmohamed observes another common conundrum. “Muslim consumers go to these brands because they have a particular look that they're trying to buy,” she notes. “The challenge is how to retain that look for a modest market without just taking your core collection and sticking some long sleeves on it. I don't think brands have quite figured out how to do that yet.”

Some have responded by partnering with modest designers, such as the US department store Macy’s. In 2018 it teamed up with a modest label, Verona Collection, to launch a line of dresses, tops and trousers.[11] “That’s quite smart because they can trust that collaboration to produce the kind of clothes that the buyers want,” Ms Janmohamed says.

Ms Zargarpur agrees. If “mainstream and modest come together in partnerships and collaborations,” she argues, “that’s where a huge chunk of the industry success would lie”.

Future priorities

Sustainable and ethical fashion has become a growing priority among modest labels, linking planetary and social responsibility as part of their ethos. “It might be part of my ethics to cover my body in a certain way but if the way the textiles were grown is harming the planet, or the factory in which they were produced is underpaying staff, then that's not ethical,” explains Professor Lewis.

Importantly, there is space for brands to grow their limited Ramadan collections and to push the boundaries of high fashion. “If you look at the grassroots shops which have been set up, many of them share a similar [look],” says Ms Janmohamed. “[If you seek] cutting-edge fashion there's a lot less available, so there is room for brands to really create exciting fashion.”

Designers may also find success by catering to a variety of tastes and interpretations of modesty. For instance, whereas shoppers in Africa or Turkey might favour bright colours and bold prints, “one solid colour” tends to be the choice in Saudi Arabia, notes Mr Ture. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach for the modest woman,” he explains. “You need to go the extra mile, to be closer to the consumers, to understand what they want.”

Even after a decade of growth in modest fashion, young Muslims are clamouring for clothes which allow them to express their identity. The market opportunity is there—the only question is whether Western brands are finally ready to seize it.