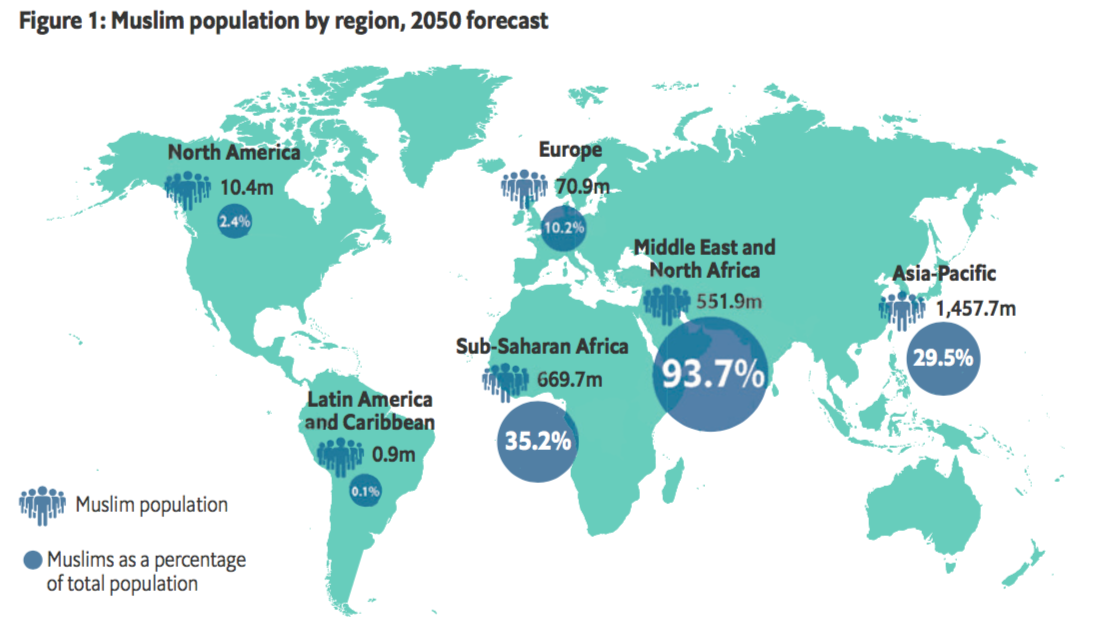

The halal food and beverage sector is the biggest slice of the Islamic economy pie, comprising over 60% of the total. Spending on food and drink by Muslims is forecast to reach US$2trn by 2024 from US$1.4trn in 2018 [1]. Its importance and appeal are based not just on the size of the global Muslim population, estimated at some 2bn, but the concentration of Muslims in regions like South Asia. These populations will offer sizeable markets for food companies in the medium to long term.

To cater to this, many global food and drinks brands—including Cargill, Nestle and Unilever—have established halal portfolios while entrepreneurs in the West are spotting opportunities. In Italy halal-compliant mozzarella is being produced for the Muslim market and halal baby-food manufacturer For Aisha is finding success in the UK. [2] In Asia, South Korea’s Samyang Foods has expanded overseas, opening a halal ramen plant in Malaysia [3] and Thailand’s CP Foods plans to create an export hub in Vietnam. [4] In fact, according to the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the main suppliers of halal products to its 57 member countries are non-Muslim, including Brazil, India, Australia and New Zealand. [5]

Source: Pew Research [6]

Halal food’s global footprint means that certification is all the more important. In essence, certification assures the consumer that Islamic law has been followed at multiple stages in the journey of an animal-based food or ingredient, spanning preparation methods, storage, processing and transportation. While in Muslim-majority countries such as Saudi Arabia all food and beverages are halal by law, the designation becomes crucial for Western or Asian brands that want to sell into these markets or for those targeting Muslim communities in non-majority countries.

Rules for halal meat preparation

- The animal must be healthy at the time of slaughter

- The animal must be slaughtered by a Muslim by hand through a single swipe of a sharp knife through the carotid artery, jugular and windpipe (to minimise pain), with blood drained out of the carcass

- Halal prohibits use of alcohol to clean knives, blades and equipment, or using flavourings and ingredients based on alcohol derivatives

- Swine flesh is forbidden

Source: Halal Food Authority [7]

Certifiably challenging

Halal food importers are strengthening standards. In Saudi Arabia, requirements for halal food storage have recently been toughened and in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Authority for Standardisation and Metrology has a legislative framework for a halal products control system and slaughterhouse registration. [8],[9] Malaysia has developed a halal business park in the south of Kuala Lumpur and adopted stricter standards for halal products. “They are taking it to the next level,” says Henrik Björkqvist, senior general manager at Arla Foods, a Scandinavian dairy company with business in Singapore and Malaysia. Indonesia has also tightened its regulations. Mandatory halal labelling for consumer products (initially food and beverages, followed by cosmetics, drugs and consumer goods) has recently been introduced and a new certification agency created. [10],[11]

But ensuring compliance becomes more difficult as the industry globalises, especially as a growing number of companies from non-Muslim geographies enter the fray and halal foods are produced and transported alongside non-halal foods. In addition, halal standards vary depending on the destination, explains Marco Tieman, research fellow at the University of Malaya and founder of LBB International, a consultancy that helps companies obtain halal certifications. “For non-Muslim countries, halal and non-halal food can be in the same container but it should be on different load carriers or pallets. But if you are sending [halal food] to a Muslim country like Malaysia or Saudi Arabia, it must be transported in a designated container.” Adhering to different sets of rules across a sprawling supply chain is a challenging undertaking.

Another aspect is the lack of harmonisation among halal certification bodies which makes it difficult for businesses to choose the right one. In Muslim countries, halal certification is led by government departments. In non-Muslim countries it is led by private sector organisations, non-governmental organisations or mosques—partly due to governments’ general separation from religious matters. “You have over 400 certification bodies in the world and most of them are private-sector,” says Mr Tieman. “In [many] non-Muslim countries there’s no accreditation for halal certification bodies, no regulations to follow, so there is a lot of fraud.”

Some countries, including Indonesia, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, require halal food imports to be certified by government-approved bodies. For companies exporting halal food from Western production sites to Islamic markets, this creates a potential business risk if the government authority decides not to recognise—or to revoke its agreement with—their respective certifier. Malaysia’s Department of Islamic Development (JAKIM) or Singapore’s Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS), for instance, approve certification bodies in Europe but the process is unpredictable, says Mr Björkqvist. “One [European] certification body could be approved by the Indonesian halal authorities but not by the Malaysian or by the Singaporean ones. It changes over time, so that's one of the challenges.” To hedge against changes, Arla Foods works with more than one European certifying authority. This increases the administrative workload but reduces the risk of the company suddenly being locked out of an Asian market.

All of this points to the need for greater harmonisation of halal standards between countries. At the international level, Standards and Metrology Institute for Islamic Countries (under the mandate of the OIC) is developing an accreditation scheme. [12] As part of this, Mr Björkqvist calls for a global certification system for halal food. “There's definitely a huge opportunity there,” he says. Emerging technologies are offering compelling solutions on this front.

In tech we trust?

There is hope that technological innovations could help improve the efficiency, transparency and reliability of halal food certification and compliance. Blockchain, a distributed database or “ledger” deemed to be highly secure and transparent, is gaining interest from industry participants.

Singapore-based WhatsHalal has launched platforms to connect players across the value chain and ease applications for halal certifications. In South Korea—whose halal market is surprisingly large thanks in part to returning emigrants from Islamic countries after the 1970s—collaboration between three entities is under way. Telecom company KT, a blockchain company called B-square Lab and the Korea Muslim Federation (KMF) have set up a blockchain-based platform for halal certification.

On this platform “every movement along the chain is time-stamped with notifications to all parties,” says Minsuk Kim, CEO of B-square Lab. “You have a real-time chain of custody: who touched what, what the product contains, when it went from one place to another. The entire chain of life of a product is [captured] on the blockchain.” Stakeholders are required to apply to KMF to gain access to the platform.

Huhnsik Chung, a blockchain expert and advisor to the project, sees blockchain as a powerful intervention that does not actually require massive process overhauls. “You can add the blockchain [solution] to critical points in your existing platform rather than replacing everything,” he says. “On the front end the platform is very intuitive and it doesn't change much from what people are using already.”

The group hopes their system could lay the foundations for global blockchain-based certification approaches. Each government’s certifying authority would review the journey to ensure the product has met the halal requirements in their country. The potential for automation adds value, says Mr Tieman. A breach in protocols can be flagged and the specific source of contamination can be identified in real time. Overall, the traceability it offers allows for better enforcement, he claims.

But there are broader challenges with the system that blockchain cannot resolve. Although technology can capture some information and feed it into the blockchain automatically—such as identifying other items halal food is stored with using radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags—there are physical elements of the process that are not tamper-proof. Halal authorities still need to inspect slaughterhouses to see if Islamic requirements are followed, explains Mr Tieman.

Rethinking halal

In the future, certification could expand to include more dimensions of increasing relevance to conscientious consumers. “I think we could weave in more quality aspects within the halal certification,” says Mr Björkqvist. These could refer to exclusion of additives, environmental sustainability of products or promotion of animal welfare. In China in particular, the halal sector enjoys popularity partly for food safety and hygiene considerations. [13]

“Now you see companies are slowly addressing halal throughout the supply chain from a risk and reputation management point of view,” says Mr Tieman. The overlap with food safety and hygiene could mean that the same authorities could verify that halal standards are being met, creating operational efficiencies.

Looking ahead, the industry might also need to grapple with esoteric innovations like “clean meat”. This is meat grown from animal cells in labs which therefore cannot meet halal compliance over slaughter yet do not breach any principles of Islamic law. [14] The challenge for the industry will be to uphold the essence of Islamic law in an era that its authors could scarcely have imagined.