Italy has a national health service that provides universal coverage for its citizens, although access to healthcare varies by region and income group.1 The Economist Intelligence Unit analysed the country’s specific policy approach to the management of a chronic skin disease called atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as eczema.

Overall, Italy was in the middle territory of eight countries analysed in meeting the 12 indicators in the scorecard. It did well in indicators that scored the use of validated disease severity measures and the availability of patient advocacy and support groups.

The scorecard was developed on the findings of a literature review and input from an expert panel. It is included in a new Economist Intelligence Unit report on AD that assesses the burden and psychosocial impacts of the disease.2

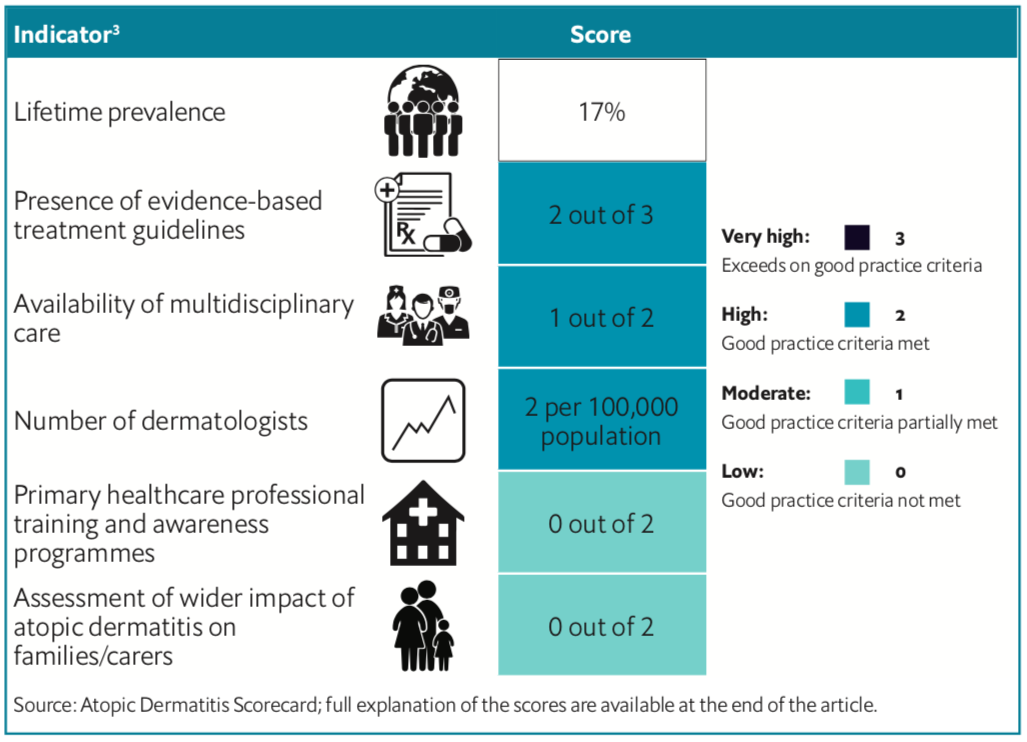

The scorecard contains policy indicators of importance to the management of AD (see below for the full scorecard results for Italy).

Global prevalence for AD ranges from 15-20% in children and 1-3% in adults.3 According to the scorecard, around 17% of people in Italy would have AD at some point intheir life—known as “lifetime prevalence”.4 An eight-country survey (performed in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan, the UK and the US) found adult AD point prevalence ranged from 2.1-4.9%, with the highest figure noted for Italy at 8.1%.5 And a survey of 1,369 children in Italy conducted in 2000 found a point prevalence of 5.8% and reported lifetime prevalence of 15.2%.6

Although high, this is not as high as the lifetime prevalence noted for other countries in the scorecard, such as Australia (32%) and Taiwan (24%). However, the figure is old—dated from 2006—so more up- to-date data would assist policymakers in designing better services for patients and caregivers.

According to a 2015 study,7 research on the prevalence of AD in Italy has mostly been on children. In the study’s survey of 10,000-plus adults across Italy, the prevalence of “current” eczema in adults was found to be 8.1%. The study concluded that eczema is highly prevalent in young Italian adults, especially women.

A population-based paediatric study looking at the prevalence of frequently occurring skin diseases (PSDs) in Italy found that incidence estimates (new cases/1,000 person-years) for most PSDs increased from 2006 to 2012, the highest being for AD, followed by acute urticaria and contact dermatitis.8

A separate 253-patient study assessing adult AD patients in Italy found that severe disease was more common in persistent AD patients compared with those with adult-onset AD. It also found that pruritus intensity was higher in adult-onset disease; and when looking at co-morbidities, hypertension was more frequent in the adult-onset group.9 In terms of AD features, the main clinical morphology of AD lesions was represented by an erythemato-desquamative pattern (74.3%), followed by a lichenified one (16.2%); exudative lesions were less frequently registered (4%).

AD can also have an impact on household budgets, with an increasing cost in proportion to the increasing severity of the disease. A study, published in 2006, looking at the economic impact of the disease in 33 families with young children with AD found that there was an annual average cost of €1,254 (US$1,540) for each family.10 The main expenses related to the use of moisturising therapies and private specialist consultations. The annual family average cost was lower for children with mild AD compared with those with moderate to severe AD.

Provision of care

Often AD is managed in primary care, but physicians do not always receive full training on the management of the AD that would better support patients. Italy’s healthcare system relies on family doctors to act as gatekeepers to access specialists.11 In the scorecard, Italy scored zero for the availability of nationwide primary healthcare professional training and awareness schemes. The Italian Society of Medical and Surgical Dermatology, Aesthetics and Sexually Transmitted Diseases supports dermatology specialists but not primary healthcare professionals. This is also the case with the Italian Society of Pediatric Dermatology.

When AD becomes complex, dermatologists can assist patients in the better management of the condition, but the scorecard found that coverage in Italy was low, with only two dermatologists per 100,000 people.

A survey of 1,500 adult Italians found that the general practitioner was the first healthcare provider consulted in the case of skin problems for 73% of those surveyed, with only 27% referring directly to a private dermatologist.12 In the case of childhood dermatitis, 52% indicated the paediatrician and 38% the dermatologist as the reference specialist.

Moreover, Italy does not have its own guidelines for the management of AD for both adults and children and relies on regional guidelines, known as the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) Guidelines for the Treatment of Atopic Eczema (Atopic Dermatitis), which were updated in 2018. There are two separate Italian consensus conference documents for the management of the disease in children13 and in adults with moderate to severe disease.14

The EDF guidelines advise that “a multidisciplinary approach including psychological advice is needed to overcome the painful, itching and stigmatising flare-ups and [patient and caregivers’] impact on quality of life”.

But as the EDF does not list what types of healthcare professional should make up this multidisciplinary approach, the scorecard only gives Italy a score of 1. Separately, theconsensus conference on children, though, does state the make-up of a multidisciplinary team, noting that it be comprised of the specialist physician (pediatrician, allergist, dermatologist), the psychologist/ psychotherapist, and other professionals, such as nurses. The consensus conference on adults mentions that in the presence of co-morbidities, multidisciplinary management of AD patients is recommended.

In addition, the EDF guidelines make no reference to the wider impact of AD on families and carers, meaning it scores zero for this indicator. Parent education programmes exist in some countries like Germany to promote parents’ knowledge and skills around managing AD. Selected elements of a German model were evaluated in Italy with 30 parents of young children with moderate-to-severe AD.15 The investigators found improvement in AD-specific quality of life after participation in the programme, but change in disease status was not evaluated.

Full scorecard results for Italy are available in the downloadable article

REFERENCES: