Australia has a mixed healthcare system that combines state-funded and private care, with active partnership between the two systems.1 In 1984, Australia introduced a system of universal medical insurance, known as Medicare.2

Three levels of government are responsible for providing care: the federal government offers funding and support to the states and healthcare professions, as well as subsidising primary care providers; states and territories have responsibility for public hospitals, ambulance services, community health services and mental health; and local authorities play a role in delivering community and preventive health programmes.3

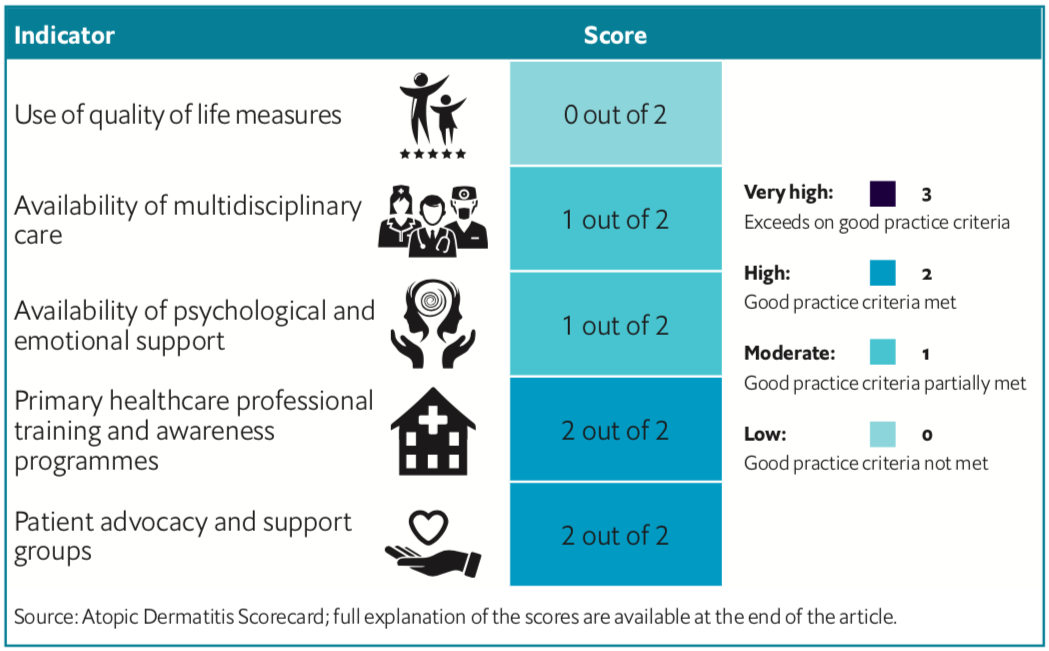

Australia was assessed across 12 policy indicators on how well it manages atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic skin disease that can have psychological impact on patients.

The Economist Intelligence Unit created a 12-indicator Atopic Dermatitis Scorecard, which contains indicators of importance to the management of the disease, including the provision of care and support for patients and caregivers (see below for the full scorecard results for Australia). AD is a disease often misunderstood, according to a recent Economist Intelligence Unit EIU report, which analysed the complete scorecard.4

Overall, Australia scored on the lower end of the eight countries analysed in meeting the 12 indicators, despite having the highest rate of lifetime prevalence in the scorecard countries. Guidelines lacked recommendations around the use of validated disease severity measures and quality-of-life measures. The country performed better in provision of primary healthcare professional training and awareness programmes, and in the availability of patient advocacy and support groups.

Burden and lack of national guidelines

Around 32% of Australia’s population will have AD at some point in their life. In terms of morbidity and costs, a small 2004 Australian study found that 21% of a cohort of 85 people with AD felt embarrassed by their skin,15% reported problems with treatments, and out-of-pocket costs for medical consultations ranged from zero to over A$800 (US$573) per individual.5 A later 2015 study looking at childhood AD in the Asia Pacific region estimated that the direct costs of AD per patient per year ranged from US$199 in Thailand to US$4,842 in Australia.6

Despite this high burden, Australia’s health service uses regional guidelines developed in conjunction with the APAC rather than its own national evidence-based treatment guidelines.7,8 The country’s health providers also have no tools available for assessing the quality of life of AD patients, despite some studies that point to a clear impact on families with children suffering from the condition.9 Meanwhile, in common only with Taiwan, Australia has no specific recommendations for the use of validated disease severity measures.

Knowledge gaps

Patients can see dermatologists directly without a GP referral, but under Medicare they will be billed for a non-referred consultation and will not be reimbursed by Medicare.10 Median wait times for urgent specialist clinic appointments with dermatologists can be up to 30 days in some states of Australia.11 Many patients with dermatology conditions in Australia are managed by General Practitioners (GPs) but GP knowledge varies significantly, according to an 2017 article in the Australian Family Physician.12

One consequence, the article notes, is that the country’s GPs have uneven knowledge about the use and safety profile of topical corticosteroids in treating AD, which can contribute to “exaggerated risk messaging that reinforces misinformation...and can directly affect treatment adherence”.13 This situation is further complicated by the fact that there is no financial reimbursement of many over-the- counter medicines to treat AD, with annual out-of-pocket costs to AD patients estimated at A$2,000 per year.14

Support for patients and carers

Australia scores in the middle of the scorecard countries for recommendations around psychological and emotional support for AD patients, as the APAC guidelines mention having psychologists as part of a multi-disciplinary team. The guidelines do not recommend specific interventions and a referral process. Research have shown there is a causal impact between AD and psychosocial problems15 and that patients do better when they have access to psychological care.16

Further professional training on AD for primary healthcare providers has been identified as a key factor in boosting patient outcomes and quality of life.17 Australian primary health practitioners have good access to professional training and awareness programmes related to AD, according to the scorecard, with the country scoring 2 pointsout of 2. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners has a Certificate of Primary Care Dermatology, including a module on eczema. Only the UK gains similar scoring on primary health training in the scorecard.

Yet, the country does better in ensuring availability of patient advocacy and support groups, receiving the highest score for this category, with the Eczema Association of Australasia (EAA) committed to supporting patients, carers, and the wider community about the condition.18 It provides free information about the condition, including links to videos, undertakes surveys of patients, and offers advice via the telephone.

Full scorecard results for Australia are available in the downloadable article

REFERENCES