A drive along any of Beijing’s congested ring roads at rush hour can test the patience of the most jaded commuter. Although various aspects of city living in Asia’s biggest metropolises are taxing, grinding traffic often evokes a particularly primal response—as evidenced by the 17m incidents of “road rage” that beset China’s streets in 2015.1 Yet as cities expand, issues of urban sprawl like traffic become all the more acute. This has implications beyond simple inconvenience—it can affect one’s mental health in various ways. Research done predominantly on Western cities has shown higher rates of psychiatric disorders among city dwellers than their rural counterparts.2

For Asia, the link between urban living and mental health is only starting to come to light. Given that East Asia saw 200m people move to cities from 2000-10,3 much is riding on how people respond to the mental pressures of urban living in this fast-growing region. To gauge the impact of urban development on mental health, The Economist Intelligence Unit conducted a survey, supported by Pure Group, of 1,000 residents across five Asian cities: Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Singapore and Taipei. The findings suggest that density in its raw form is not the chief determinant of mental pressures among city residents. People’s perceptions of personal space do not necessarily correlate with actual crowding; rather, urban sprawl, and the change caused by a city’s rapid expansion, are just as likely to impede people’s feelings of personal space and lead to mental stress.

GROWTH SPURT

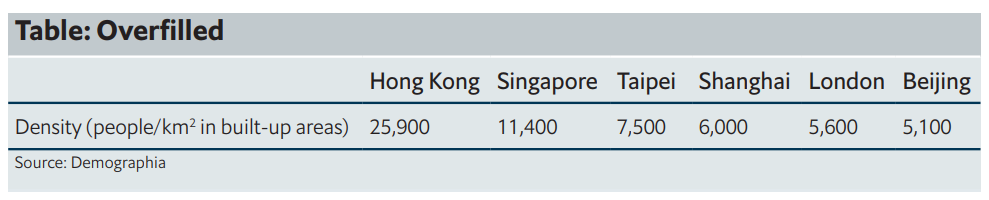

The cities we explore range from the extremely crowded (Hong Kong) to only moderately so by global standards (Beijing).

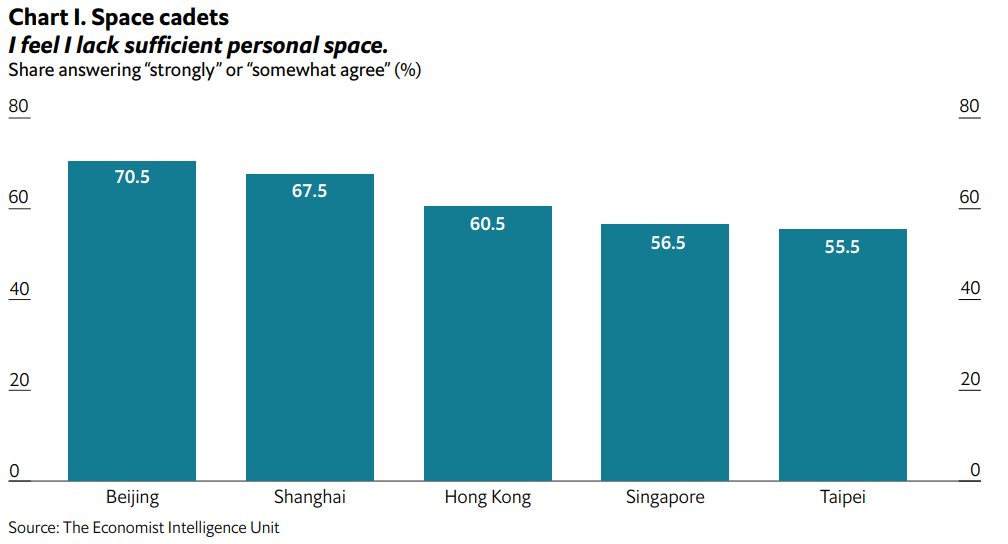

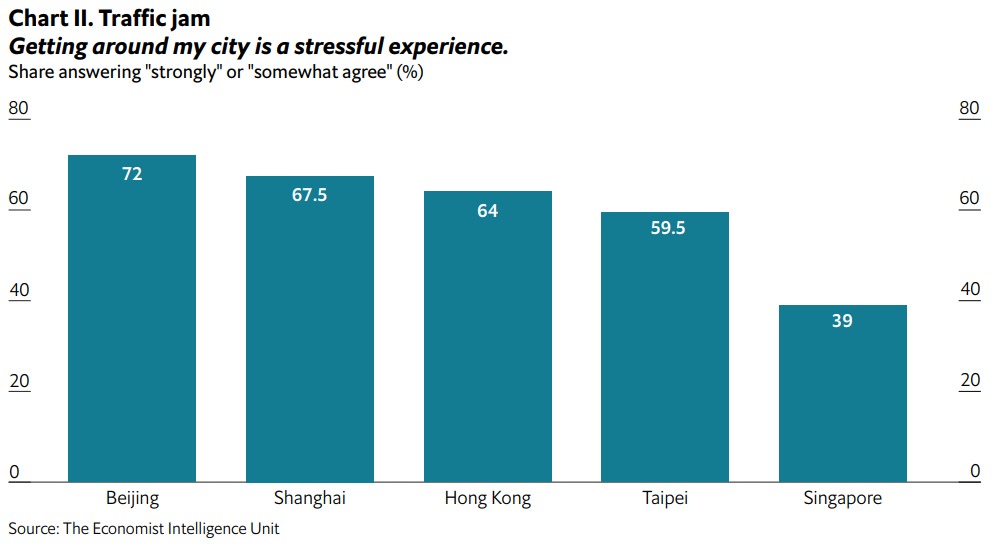

Yet residents of the less-dense cities in the sample—Beijing and Shanghai—report mental pressures that equal or surpass those reported by residents of Hong Kong, Singapore and Taipei. Beijingers strongly agree that their city suffers from overcrowding to a higher extent than other cities; Beijingers and Shanghainese agree to a higher extent that they lack sufficient personal space; and Beijingers feel more stressed out by their commute.

This could be due to urban sprawl: Beijingers and Shanghainese have endured rapid geographic enlargement in recent years. Beijing’s urban area increased by 6.7% per year from 1999-2013, compared with a global average of only 4.3%,4 while from 1991-2000, Shanghai’s shot up by 6.6%, versus 5.9% globally.5 Shanghai’s built-up areas now occupy 14 times as much land as Hong Kong’s,6 while Beijing recently opened its seventh ring road, measuring a whopping 1,000 km.7

Layla McCay, director of the London-based Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, says that in sprawling cities people often end up living in remote housing that lacks community and lifestyle facilities. “Being able to live close to employment, social and cultural opportunities is beneficial to people’s mental health, while being isolated…can be detrimental,” she says.

Global studies have shown links between urban sprawl and detrimental effects ranging from loss of natural habitats to greater wealth disparity.8 The increased hassle from long commutes may be a particularly damaging effect of sprawl, as the findings from Beijing, the most sprawling city in our sample, demonstrate. “The longer you spend in transit each week, the less time you spend with your friends and family and less time you have for leisure opportunities,” says Ms McCay. “Commutes represent a lost opportunity.”

The sheer pace of urban change, rather than simply its magnitude, may also play a role in the mental pressures felt by our Beijing and Shanghai sample. Research has shown a correlation between urban expansion and depression in China.9 Juan Chen, associate professor of applied social sciences at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the leading author of the urbanisation and mental health study, speculates that rapid changes in the urban landscape can lead to feelings of dislocation and unhappiness. “In cities like Beijing and Shanghai, you see so much construction going up overnight, which leads to many changes in people’s everyday life experiences,” she says.

On the other hand, high urban density, when managed well, has been shown to increase quality of life and boost positive mental outcomes. When complemented by robust infrastructure—something that Hong Kong and Singapore have in abundance, according to the World Economic Forum, which ranks the two cities first and second, respectively, in a global ranking of the quality of physical infrastructure10—density can raise convenience by promoting the agglomeration of goods and services and shortening commutes.11 One European study showed a negative correlation between higher urban density and increased risk of depression.12

CITIES ON THE MOVE

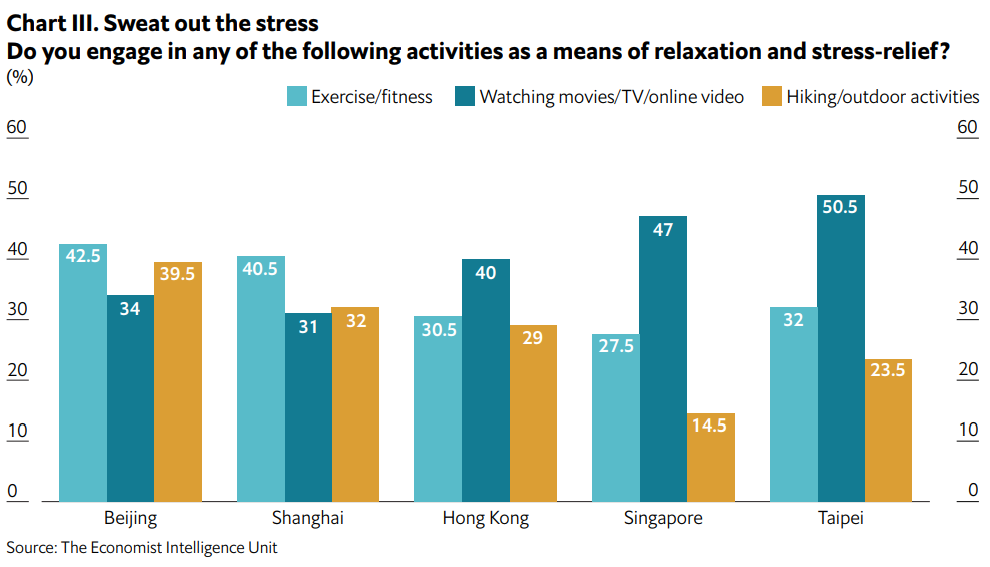

How residents of our five cities cope with the pressure of urban living are also split along the dense/sprawling divide. According to our survey, Beijingers and Shanghainese show a much higher propensity towards active release outlets like exercise and hiking, while Hongkongers, Singaporeans and Taipeinese are, comparatively, glued to the TV.

This could reflect a potential benefit to sprawling urban areas, despite all their ostensible drawbacks: more readily available outdoor space to enjoy physical activity, such as the group dancing popular in many Chinese cities. Climate may also play a role; both Ms McCay and Ms Chen emphasise that hotter, tropical environments like those in Hong Kong and Singapore deter people from spending time outdoors.

Other popular outlets include shopping and socialising with friends and family, both of which were cited by about a quarter of all respondents, and reading, noted by nearly a fifth. Using social media garnered slightly less support than reading, an interesting finding for this smartphone-addicted region. Regardless of the outlets people utilise, countering the negative effects of urban development will become more pressing as cities in Asia continue adding people and, potentially, sprawl.