Asian cities rank among the densest environments in the world, characterised by high-rise apartment blocks, teeming streets and jam-packed transport systems. Whether the cities of today are likely to grow or shrink tomorrow strongly influences residents’ attitudes—and it is clear that not all cities in Asia are moving in the same direction.

To gauge this sentiment, The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) conducted a survey, supported by Pure Group, of 1,000 people across five Asian cities: Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Singapore and Taipei. The results reveal that Beijing and Shanghai residents are unhappy about current overcrowding but far more sanguine about the future, whereas Hong Kong and Singapore show the opposite pattern, and Taipei falls in the middle. This is probably due to official initiatives in mainland China to restrict inflows of people and boost its cities’ capacities to handle more residents—a strategy that many would like to see emulated in Hong Kong and Singapore.

FEELING THE SQUEEZE

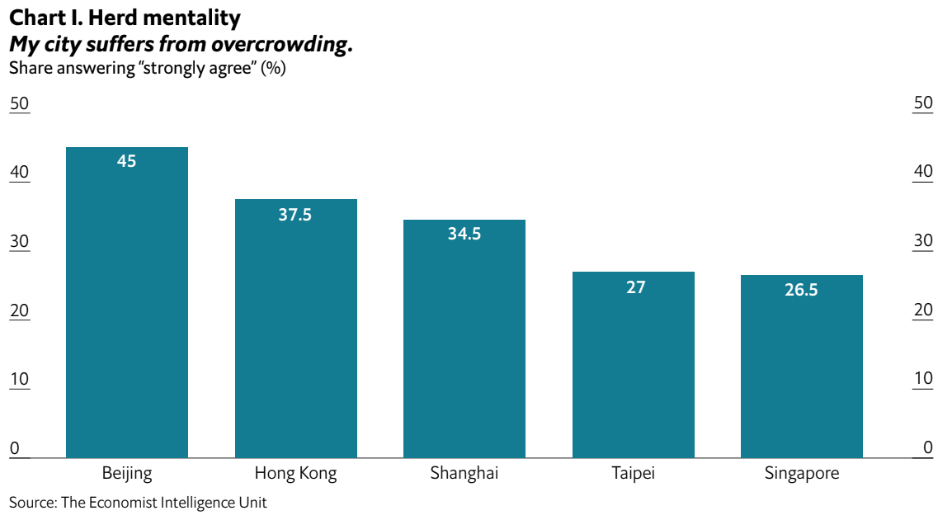

Despite living in the least densely populated of the five cities, with 5,100 people per km2, 1 almost half of Beijing respondents “strongly agree” that their city is overcrowded, the highest among our sample. Beijingers also feel most strongly that overcrowding causes pollution in their city, which is notorious for smog.

Significantly fewer people in Hong Kong think their city is overcrowded, despite it being the most densely packed of the five, with over 7m people squeezed into 264 km2 of built-up land.2 Singaporeans live in the second-most densely populated city but have the lowest perception of overcrowding of all.3

These surprising results reflect the cities’ disparate geographies. Beijing has expanded to an endless urban sprawl, whereas in Hong Kong, it is relatively easy to access the territory’s many hills and hiking trails, while the Singaporean government’s “Garden City” vision has created a verdant city with 300 parks and four nature reserves.4

Yet feedback was not universally positive in those two cities either. Respondents in Hong Kong, where business and shopping districts are clogged by pedestrians, feel most strongly that their sidewalks are overcrowded, while as many Singaporeans as mainland Chinese express negative sentiments about their public transport systems. This may be due to recent population growth, which reports claim have put the metro under strain.5 In addition, “Singaporeans have very high expectations” for efficiency, says Lily Kong, provost and chair of social sciences at Singapore Management University. Taipei residents, meanwhile, express concerns about the impact of overcrowding on pollution to a greater extent than those in other cities, bar Beijing.

FACING THE FUTURE

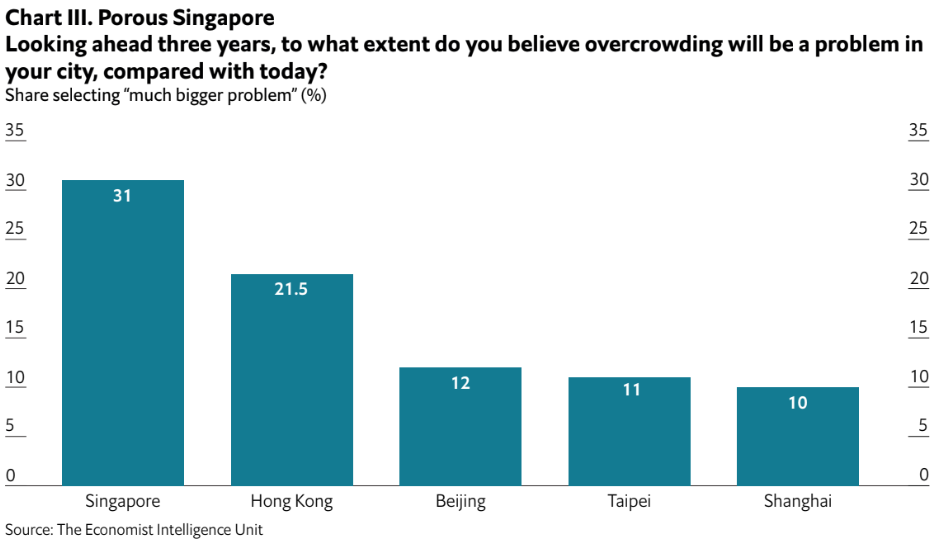

Though overcrowding is clearly a problem now, the way residents of different cities anticipate the future varies markedly. Compared with Beijing, Shanghai and Taipei, twice as many people in Hong Kong and three times as many in Singapore anticipate that overcrowding will become much worse.

This contrast reflects each city’s mix of immigration policy and urban planning initiatives. Beijing and Shanghai have experienced a period of phenomenal growth: from 2000 to 2016, Shanghai’s population grew by 47%6,7 and Beijing’s by 59%, as migrant workers poured in from rural areas,8 spurring city planners to take action. Authorities have capped populations, torn down informal housing in Beijing, shed manufacturing facilities, and drawn up plans to expand green areas and improve public transport.9 The impact is already being felt; last year, the populations of both cities dipped for the first time since 1978.10

Beijing is also carrying out a five-year initiative to reduce the number of cars on its roads, and encourages residents to walk, cycle or use public transport.11 Additionally, authorities have set ambitious targets to clean the city’s air: during the winter of 2017, air quality showed a marked improvement over the previous winters.12 According to Juan Chen, associate professor of applied social sciences at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, “Beijing urban residents are quite aware of [these interventions] and see that the policy is effective.”

In Hong Kong, by contrast, concerns about immigration stem from the Chinese government’s agenda of greater integration with the mainland, while property purchases by mainland Chinese have contributed to the territory’s skyrocketing house prices.13 In Singapore, immigration is also a hot political issue. Beginning in the 1980s, foreign workers were brought in to alleviate a labour crunch and boost the economy—immigrants now make up 40% of the population.14 Although they have underpinned the nation’s stellar economic performance, the swelling population has led to a backlash by some residents who disagree with the government’s policy.15

MAKING CHANGES

Although immigration policy is usually a top-down exercise, residents in our surveyed cities are hardly powerless in shaping their neighbourhoods. Nearly one in four respondents said they would “actively put forth suggestions about reducing overcrowding to city, district and community officials”. The channels they utilise vary: according to Ms Kong, “Hong Kong has an active NGO [non-governmental organisation] sector that will find means of engaging”, while “in Singapore, the urban planning authority is active in soliciting feedback, often organising engagement sessions”. In Taipei, systems such as the i-Voting digital platform facilitate citizen engagement; members of the public have used it to express their opinion on certain urban planning proposals, such as the development of Shezidao, a low-lying area prone to flooding.16,17

In mainland China, central authorities exert tighter control over planning,18 though residents of Shanghai and Beijing are able to exert influence at the grassroots level. Ms Chen, who has carried out research in Beijing, says that some people she has interviewed feel empowered by excluding migrant workers from using public facilities like community centres. Though this may smack of nativism, it’s clear that perceptions of urban overcrowding may hinge as much on controlling the inflow of people as making space for those already there.