Workers in developing countries are already jittery with worries ranging from “rebound” outbreaks and lay-offs to the onset of cabin fever.

As if workers don’t have enough on their minds, the covid-19 pandemic is resurfacing another concern: the one about technology’s impact on the future of work. Specifically, recent research suggests that the deepening recession is likely to bring a surge of labour-replacing automation.

But what’s the connection between recessions and automation? On the surface, the implacable infiltration of automation into the economy would seem to be a steady, longer-term trend rather than an immediate fact. Likewise, it might seem intuitive that any rise in unemployment in the coming months will make human labour relatively cheaper, thus slowing companies’ move to technology.

Yet that’s not actually how automation works. Unfortunately for the workers poised to be affected, robots’ infiltration of the workforce doesn’t occur at a steady, gradual pace. Instead, automation tends to happen in bursts, concentrated especially in bad times such as in the wake of economic shocks when humans become relatively more expensive as firms’ revenues rapidly decline. At these moments, employers can benefit by shedding less-skilled workers and replacing much of what they do with technology, while often investing in higher-skilled workers, which increases labour productivity as a recession tapers off.

Ultimately, such cycles of workforce reallocation may well improve the efficiency of the economy for the longer-term good of society. But along the way, and in the nearer-term, such cyclical surges of technology adoption tend to be disruptive, unequal and unhelpful to the cause of maintaining employment during a crisis.

Nor are these disruptions only speculative. Several economists have extensively documented the cyclical, selective nature of automation and employment disruption. Nir Jaimovich of the University of Zurich and Henry E. Siu of the University of British Columbia have reported that over three recessions in the past 30 years a whopping 88% of job loss took place in “routine”, highly automatable occupations—suggesting that automation accounted for “essentially all” of the jobs lost in the crises. Separately, Brad J. Hershbein of the W.E. Upjohn Institute and Lisa B. Kahn of the University of Rochester looked at almost 100m online job postings before and after the Great Recession and found that firms in hard-hit metropolitan areas were steadily replacing workers who performed automatable “routine” tasks with a combination of technology and skilled workers. So, even as robots replace workers during boom times at places such as Amazon and Walmart, their influx surges during recessions—not great news for the world’s anxious workers.

Given the importance of social distancing and sanitation it seems likely that the coronavirus recession will see an accentuated embrace of automation technologies, whether in the form of kiosk ordering in restaurants, checkout-free shopping or robotic sanitation machines. Considering that the past decade has seen more automation and artificial intelligence (AI) applications readied for effective use than ever, it seems clear that the next few years will see more rather than less automation as the economy slows.

Cyclical surges of technology adoption tend to be disruptive, unequal and unhelpful to the cause of maintaining employment during a crisis.

As to who may be vulnerable to automation-related dislocation in the recession, the reach of technology may be wider this time round.

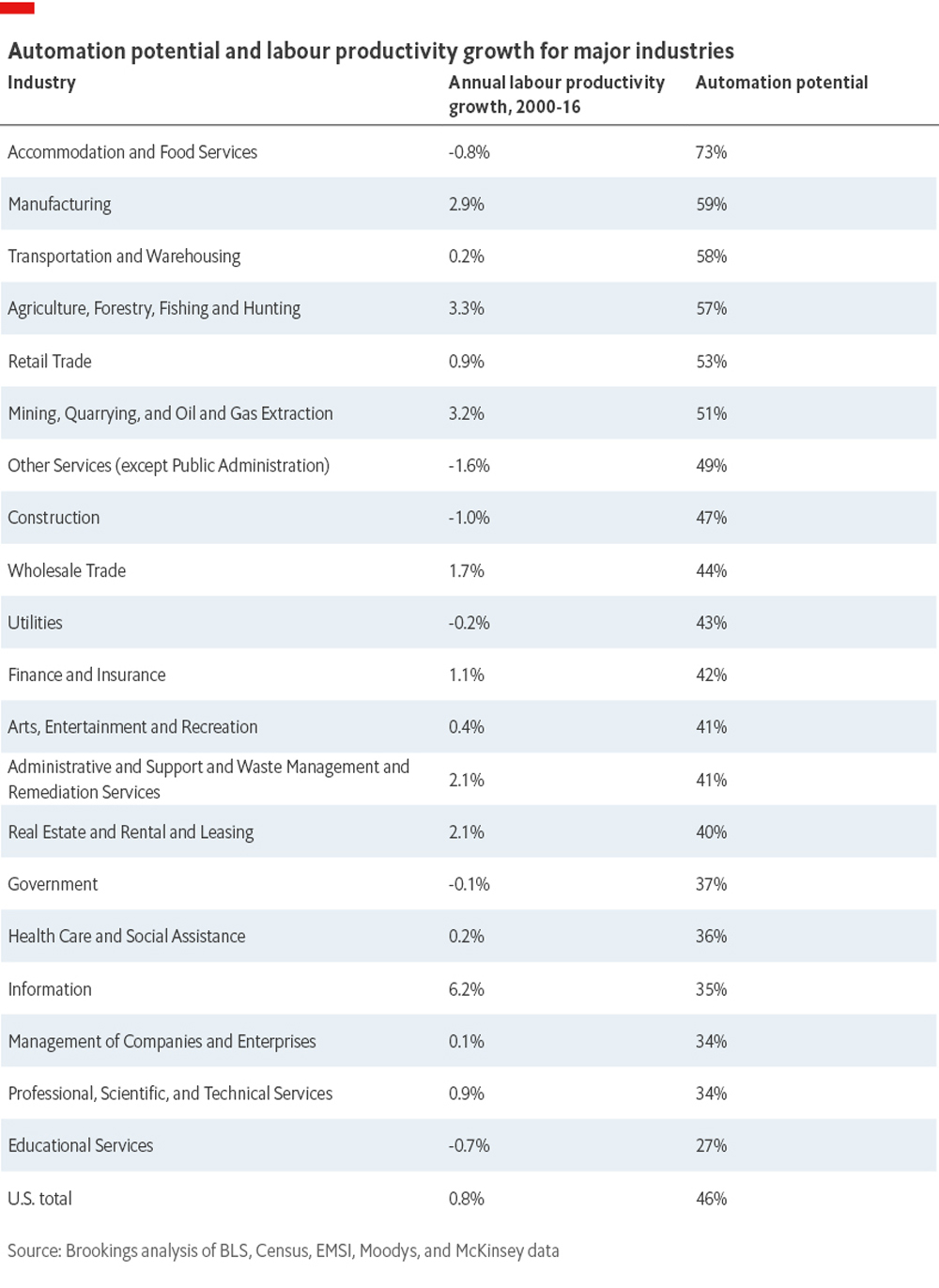

As my 2019 assessment of US automation trends suggests, it’s likely that low-income workers, the young and workers of colour will be some of the most vulnerable. That’s because the epidemic and subsequent automation surge is likely to affect the most “routine” occupations—jobs in areas such as production, food service or transportation.

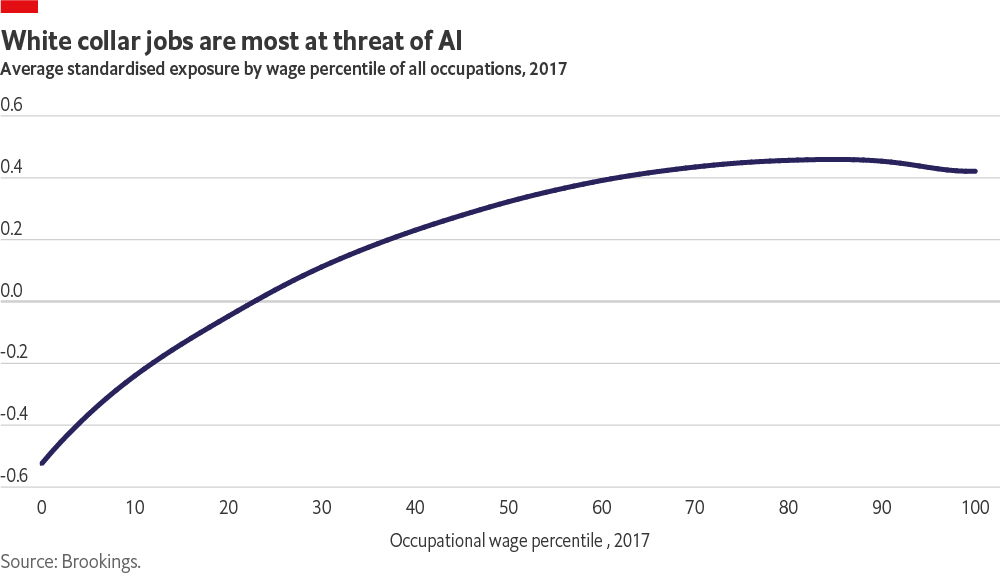

And yet that is only part of the story. During this crisis, AI may play a larger role than before as an array of algorithmic applications take on countless office functions that would be said to require higher-level “intelligence”, whether it be planning, predicting, classifying, reasoning or problem-solving. In that vein, assessments developed by Stanford scholar Michael Webb in partnership with my team suggest that if AI surges further into the economy during the crisis it may affect better-paid, white-collar or professional workers more than the less-educated, lower-wage workers who have tended to be most affected by robots and software.

Workers in higher-wage occupations will generally be more exposed to AI than lower-wage workers. The curve tapers at the 90th percentile, suggesting that the most elite workers—such as CEOs—may be somewhat protected.

That doesn’t mean that the world’s white-collar workers should all be fearing for their jobs. But it does mean that the relatively more fortunate “telework” class—market research analysts, middle managers, programmers or financial analysts—could also find themselves more involved with new and disruptive technologies. In that sense, no group of workers may be entirely immune this time around.

As to what all of this means for the future, the potential for a covid-19 automation surge reinforces the fact that the pandemic recession won’t just bring an end to a decade of plentiful jobs. More starkly, the downturn is likely to usher in a new bout of structural change in the labour market and its demand for skills.

If it continues for a while, the downturn could induce firms in food service, retail and administrative work to restructure their operations towards greater use of technology and higher-skilled workers. And it could introduce new waves of “digital transformation” into the world’s offices. From beleaguered, lower-skilled employees to professional workers, these changes will no doubt complicate an already daunting return to normality.

Mark Muro is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Economist Group or any of its affiliates. The Economist Group cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this article or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in the article.