The decoupling process of the United States and China, which has prompted investors to diversify the geographic positioning of their investments, shows no signs of abating. Decoupling, or systematically closing off economic engagement, is dismantling a long era of trade and economic integration between the two countries. As a result, U.S.-China bilateral trade in goods and services has decreased from 3.7% of U.S. GDP in 2014 to 3% in 2023,1 and U.S. FDI transactions in China have decreased from an average of US$14 billion per year from 2005 to 2018 to less than US$10 billion since 2019.2

This trajectory illustrates how investors are becoming increasingly sensitive to a variety of factors, including geopolitics, distance, market and operational capabilities. Stable energy, transport and connectivity infrastructure are also key components in making investment decisions.

A recent Economist Impact study found only 15% of executives were implementing reshoring strategies, in contrast to 47% who were diversifying their supply chains. However, reshoring is gaining importance, as in 2021, only 5% of executives were considering shifting overseas manufacturing closer to the United States. As the study found that 96% of executives surveyed were making changes to their trade operations in response to geopolitical events,3 the option to reshore will increase in attractiveness to businesses.

The reconfiguration of global supply chains represents a massive opportunity for Latin America. In 2022, the region saw total FDI inflows of over US$224 billion, the highest since 2013, when FDI flows peaked at US$188 billion.4,5 However, the region has been unable to leverage the full potential of nearshoring, defined by the transfer of business operations to a geographically closer location.

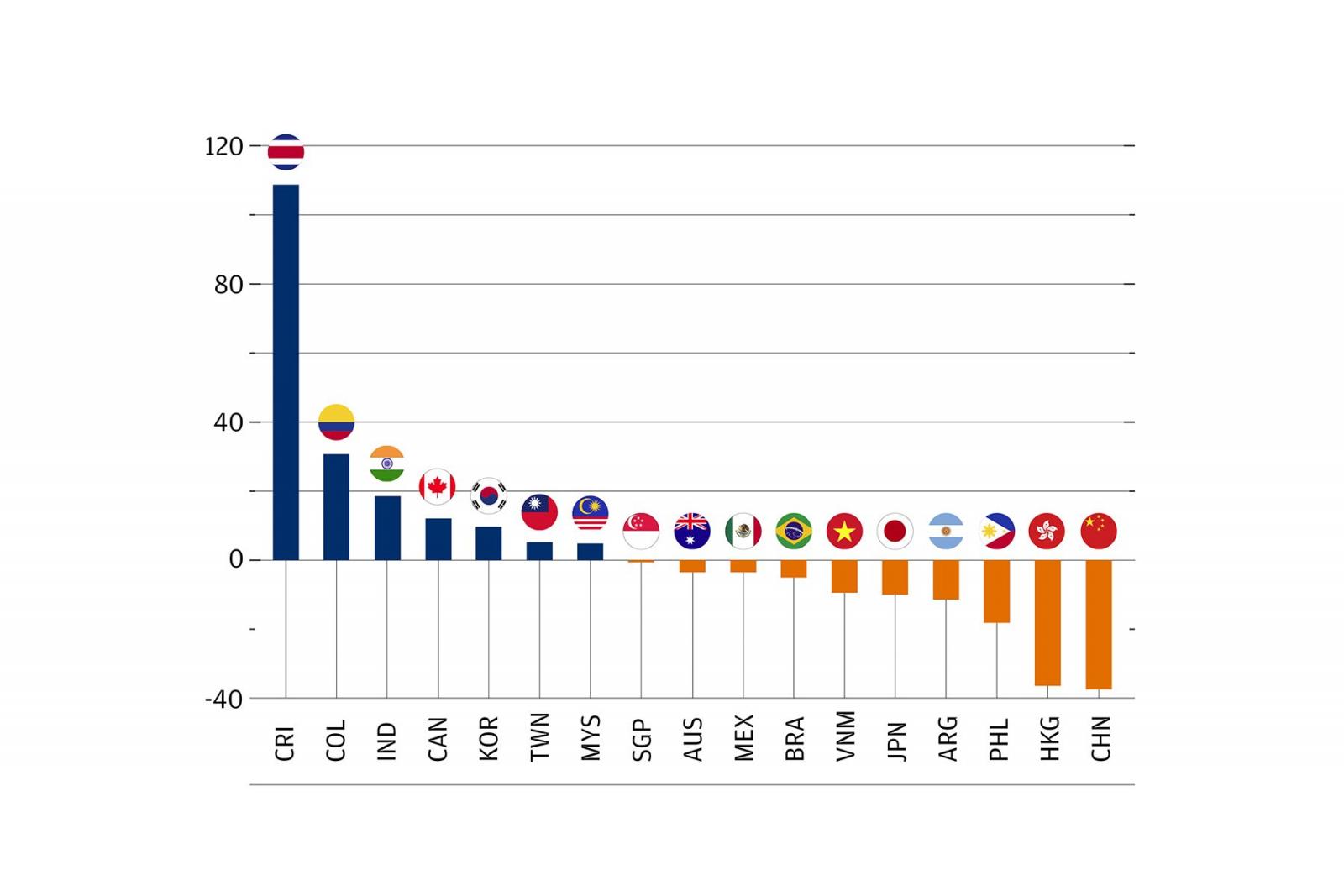

Latin America is competing with other regions, including the ASEAN bloc, the fourth-largest manufacturing hub in the world, and attracting large U.S. FDI inflows. Within the Americas, countries such as Canada, Costa Rica and Colombia have shown the greatest positive percentage change in U.S. FDI flows than Mexico and Argentina (see Figure 1).

Costa Rica, Colombia and Canada are all seeing an increase in U.S. FDI flows versus Mexico, Argentina and Brazil.

US foreign direct investment partly shifted from less to more aligned countries.

Source: IMF; published April 11, 2023.

Economist Impact is exploring the factors that are influencing investors’ reshoring decision making. In this article, we will take a deep dive into the importance of investments in critical infrastructure as key enablers of economic growth, and will discuss how Latin American countries are leveraging critical infrastructure to take advantage of the diversification of the United States’ FDI.

Critical infrastructure, including energy, air and sea ports, rail and roads, information and communications technology, facilitates ease of doing business and trade.

Despite Latin America’s strategic position that could enable the region to capture FDI outflows from China, data from the Economist Intelligence (EIU) warns of slow progress against challenges to the region’s business environment, including poor infrastructure, lack of political stability and high security risks that will make this FDI boom difficult to sustain. Anthony Kane, President and CEO of the Institute for Sustainable Infrastructure, views nearshoring in Latin America through two lenses: access to transportation, “whether that’s rail, seaports, airports at scale in order to move goods efficiently,” and access to “consistent, large and inexpensive energy.” Therefore, investing in infrastructure is a critical first step to becoming an attractive region for nearshoring. The following analyzes how the development of critical infrastructure, including roads, rail, digital, energy, ports and air, is being used by different Latin American countries to gain a competitive edge to attract nearshoring opportunities.

Safe, well-constructed and maintained roadways are imperative to transporting freight

According to the EIU Global Risk Outlook, Latin American road networks struggle to cater to growing business demands due to the degree of obsolescence, lack of maintenance and insufficient supply. According to their risk scores, Argentina, Mexico and Chile present a medium risk (2 out of 4), while Costa Rica, Brazil and Colombia present a higher risk (3). Cargo theft is an additional concern. The Mexican Association of National Transporters (ANTAC) estimates that cargo theft losses amount to US$137 million every year, while the Brazil National Association of Cargo Transport and Logistics reported cargo theft losses of US$250 million in 2022.6,7

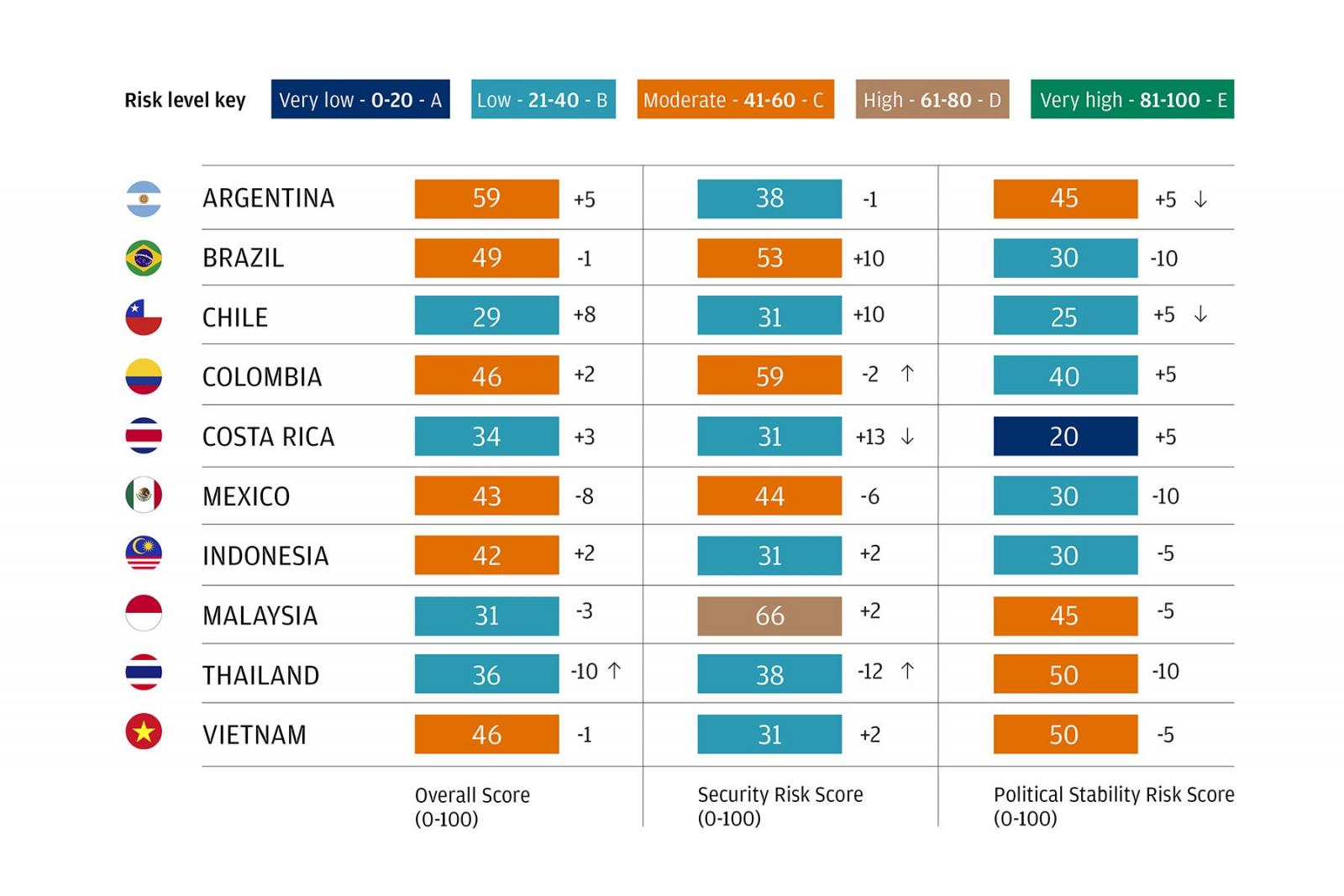

Security concerns plague the region, especially when compared to its trade competitors in Asia, such as Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand. Although both country samples show similar low-to-moderate security and political stability risk scores, Latin America has seemingly regressed since 2017, whereas the Asia country sample has made improvements (see Figure 2).

Latin America has regressed in security and political stability while their competitors in Asia make steady progress

Security Risk and Political Stability Risk Scores for sample of countries in Latin America and Asia (comparing Q3 2023 with Q1 2017)

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU); 2017-2023. Data accessed on 13 November 2023

Large-scale, cross-border coordinated projects can help improve the region’s competitiveness. The Bioceanic Corridor, a 2,290-kilometer road connecting Chile’s Pacific Ocean Coast with the agricultural powerhouse of Brazil’s Mato Grosso do Sul by way of Argentina and Paraguay, is one such example. The road, when fully completed, will decrease transport time to Asia and Oceania by 17 days. It will be used as an alternative to Port of Santos, shortening the distance and time for Brazilian exports and imports between markets in Asia, Oceania and the U.S. West Coast.9

While rail network infrastructure is key, political stability will also play a crucial role

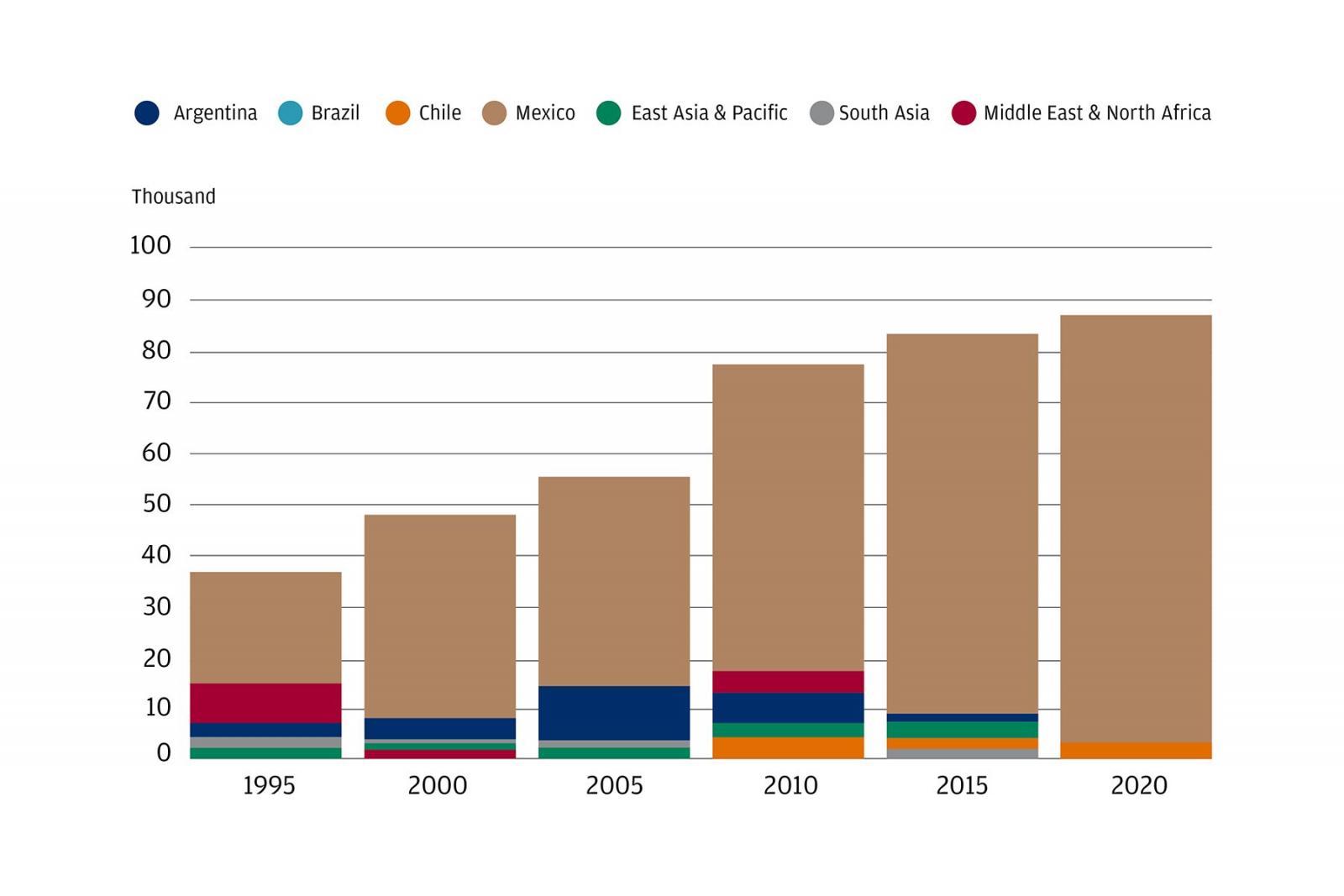

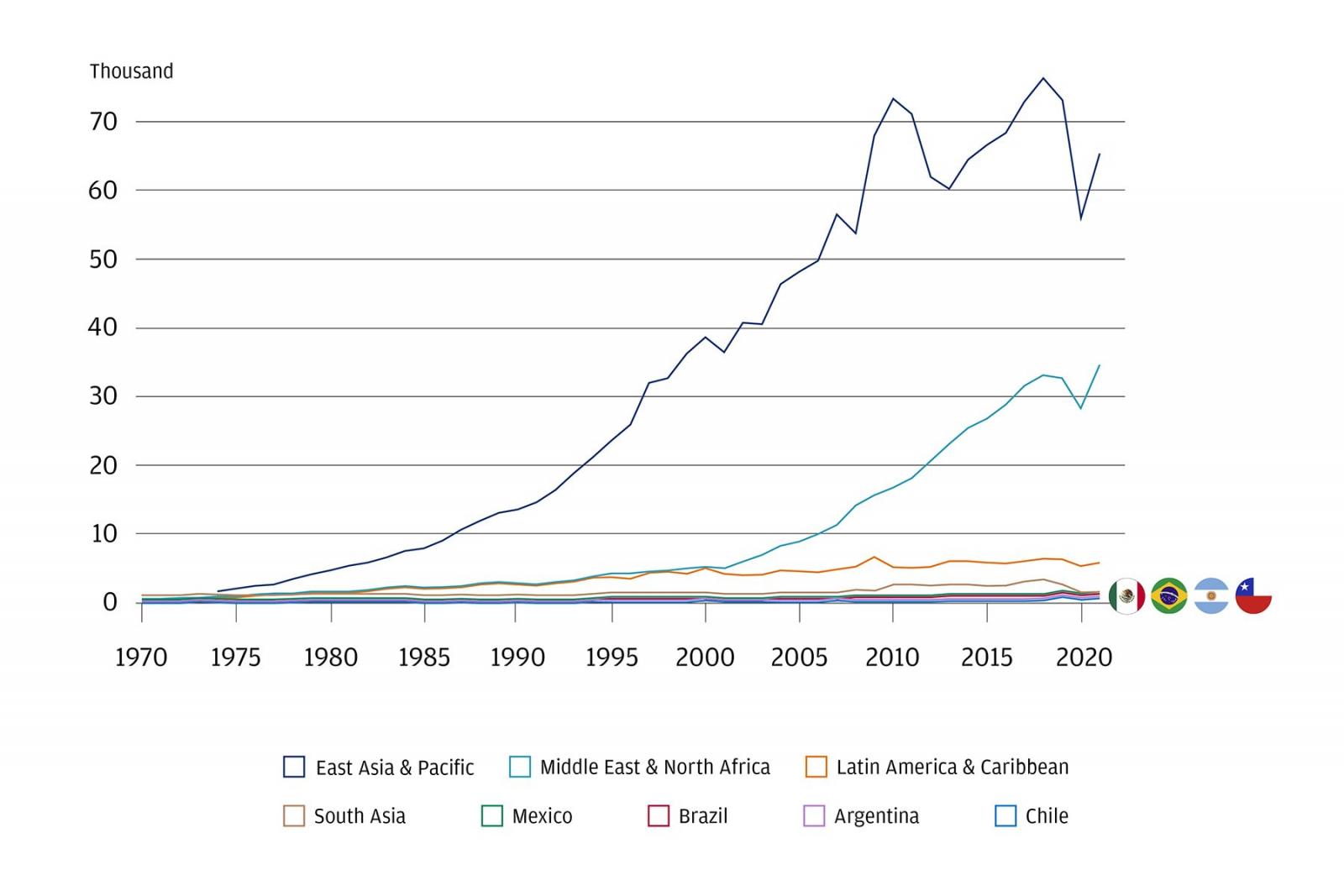

In terms of goods transported by rail, Mexico is leading against regional rivals Chile, Brazil and Argentina, as well as other regions entirely, such as East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East, and North Africa and South Asia (see Figure 3).10 “Latin America is really behind in investing in the rail sector, first because it is very expensive, and second because you really need to have a long-term plan; you aren’t building a rail system for the next few years, you’re building it for the next hundred years,” says Cristina Contreras, Co-Founder and Managing Director at Sinfranova. “Mexico has a very sophisticated freight rail system, which connects the corridor with the United States and Canada, but they have a very limited passenger rail network.”

Mexico leads in goods transported by rail when compared to LATAM and The Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific.

Railways, goods transported (million ton-km).

Source: World Bank; 1995-2021. Data accessed on 13 November 2023

Expanding this railway network is a key priority for Mexico’s President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. While increased public investment can present an opportunity, it could also become a double-edged sword for private investors. Recently, the country’s government seized part of a rail line that was deemed “public utility,” transferring it to a government entity that is building a line across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, which separates the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.11 Political stability, such as respect for the rule of law, is an important component of firms’ investment calculations and lack of that stability could hinder future willingness to invest.

Another ambitious project in the region is the Central Bi-Oceanic Railway, which is a planned 3,000-kilometer route that would run from the Port of Santos in Brazil to Puerto de Ilo in Peru (crossing 1,700 kilometers of Bolivian territory). Dubbed by some as the “21st-century Qhapaq Ñan,” it will save 31 days of time in carrying merchandise from Europe to the Pacific Ocean. While originally thought to be partially completed by 2021, the project has stalled.12

Other countries in the region, such as Chile, are trying to carry out rail plans on their own. Chile is investing US$5 billion for “Chile on Rails,” the largest rail investment program the country has ever undertaken.13

Digital infrastructure is also a key driver of competitiveness, with Latin America well placed relative to rival regions

The Bi-Oceannic Corridor project also has a digital component, including an optic fiber buildout. This new network route will connect the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans in the region through digital highways, allowing for regional connectivity.14

Overall, the region is ahead of its other developing rivals, with fixed broadband subscriptions higher than in the Middle East, and North Africa and South Asia, but behind East Asia and the Pacific (excluding high-income countries). Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and Chile are all above the Latin America average, with Colombia close behind. This upward trajectory, coupled with the EIU’s Cybersecurity Preparedness assessment for these countries, ranging from no risk in Colombia to low/medium risk in Mexico and Costa Rica, and no/low risk for their IT infrastructures, indicates that businesses will have access to stable digital connectivity to operate within the region if they decide to nearshore.

As companies around the world commit to net-zero targets, investments in clean energy become critical to attract FDI

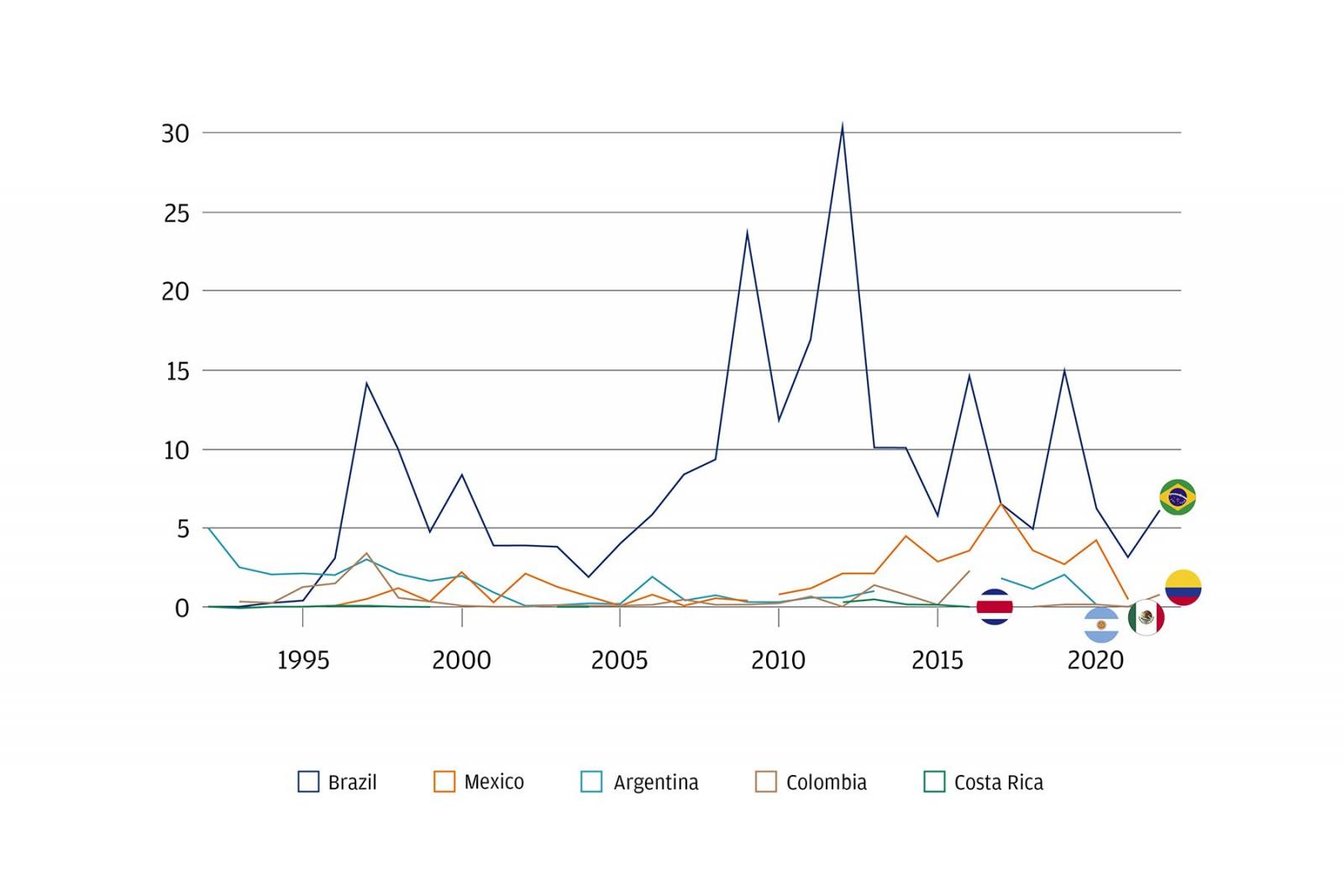

Compared to its regional peers, Brazil has spent by far the most in the last 30 years on investments in energy, with participation from the private sector (see Figure 4).15 Investments in renewable energy infrastructure projects are equally underfunded. Economist Impact’s Infrastructure for Good Index, which compares the infrastructure ecosystems of 30 countries around the world, found that in Mexico, renewable energy projects were not included in any of its infrastructure investments over the past five years. By contrast, Argentina has a 30% or more share of its infrastructure investment in renewable energy projects; Brazil is close behind, dedicating between 20% and 30% of its infrastructure investments to renewable projects.16 “I think that traditionally, investment in renewables is kind of like a low-hanging fruit,” says Contreras. “The risks are less than some other infrastructure types because they import the technology, and there is not a lot of room for unknowns.”

Brazil led investment in energy with private participation between the 1990s and 2022 when compared to Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Chile and Costa Rica

Investment in energy with private participation (dollars) in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Chile and Costa Rica

Source: World Bank; 1992-2022. Data accessed on 13 November 2023

As supply chains diversification endures, Latin America’s shipping industry invites fresh investment

While Latin America does not play a dominant role in global shipping trade (the region only accounts for 12.6% of total goods loaded and 5.8% of total goods discharged), there has been a recent surge in investments to the region in response to both growing trade volumes and sourcing shifts from diversifying supply chains.17,18 APM Terminals, a unit of the A.P. Møller-Maersk Group, is investing US$500 million in a new terminal in Suape, Brazil, and has committed another US$700 million to four other terminals and inland depots in the country. In September 2023, German company Rhenus acquired BLU Logistics, a Latin American forwarder with operations in Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Uruguay and China, as well as a majority share in LBH Group, a port agency with a presence in six countries in the region, which Rhenus attributed to the region’s positive development pace and high concentration of commodities. These examples illustrate a confidence in the region, as companies such as the above acknowledge that current geopolitical trends around supply chains are likely to endure.

Lack of air infrastructure is one of the greatest bottlenecks for trade in the region

Latin America, compared to other developing regions, including East Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, has a far inferior volume of air freight.19 Over the last 30 years, the trend line only marginally increased, illustrating the negligence of the region in expanding trade routes by air (see Figure 5).

Between developing regions, Latin America has the lowest numbers in volume of air freight.

Air transport, freight between 1970 and 2021 (million ton-km)

Source: World Bank; 1970-2022. Data accessed on 13 November 2023

For Mexico, the missed opportunity to become an air hub in the region has left space open for competitors. In 2021, the U.S. FAA Flight Standards Service, in coordination with the International Aviation Safety Assessment (IASA) Program, downgraded Mexico to category 2, after finding that it did not meet ICAO-set safety standards. This meant that Mexican airlines could not expand flights to the United States, and it prevented U.S. airlines from selling tickets on flights operated by Mexican airlines. In 2023, the United States restored its rating of 1, allowing Mexican airlines to expand flights to the United States.20

Conclusion

Given the favorable trade policy and investment trends, nearshoring is not just a pipe dream. However, the region must act to improve its business environment, including access to quality infrastructure, and improvements to political stability and security in order to capitalize on nearshoring quickly, as other regions also recognize the opportunities created by supply chain shifts and are actively competing for it. Missed opportunities for trade by air, road, sea and rail, both on domestic and regional levels, are good places to start. The region can then complement this through renewable energy infrastructure investments and doubling down on digital connectivity. It is crucial for the region to invest in itself, setting a standard for businesses that would like to do so, too.

1 https://www.chinausfocus.com/finance-economy/us-china-decoupling-by-the-numbers.

2 https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9798400224119/CH004.xml; https://rhg.com/research/big-strides-in-a-small-yard-the-new-us-outbound-investment-screening-regime/.

3 https://impact.economist.com/projects/trade-in-transition/key-findings/key-finding-6/.

4 https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8b6ca18b-6a03-425f-a67b-d569ebaea6b5/content.

5 https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/fd2ce029-2846-4900-a0e6-14818f6191b3/content.

6 https://english.elpais.com/international/2023-07-17/cargo-theft-in-mexico-a-crime-thats-costing-lives-and-hundreds-of-millions-of-dollars.html.

7 https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/nacional/saques-incendio-e-mortes-trens-de-carga-viram-alvo-de-criminosos-em-sao-paulo/.

8 EIU Operational Risk analysis (subscribers only).

9 https://www.gov.br/dnit/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/dnit-participa-de-evento-na-embaixada-da-argentina-para-discutir-sobre-corredor-bioceanico.

10 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.RRS.GOOD.MT.K6?locations=MX-CL-BR-ZJ-AR-CO-ZQ-8S-Z4-CR&view=chart.

11 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-05-19/amlo-seizes-larrea-s-railroad-in-veracruz-for-isthmus-project#xj4y7vzkg.

12 https://www.railway-technology.com/features/bi-oceanic-railway-corridor/.

13 https://www.railway-technology.com/features/chile-on-rails/.

14 https://newswire.telecomramblings.com/2023/02/millicom-tigo-reveals-new-fiber-network-at-bioceanic-corridor-that-connects-the-pacific-with-the-atlantic-ocean/.

15 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IE.PPI.ENGY.CD?end=2022&locations=AR-CO-MX-BR-CL-CR&start=1992&view=chart.

16 https://impact.economist.com/projects/infrastructure-for-good/.

17 https://unctad.org/press-material/unctads-review-maritime-transport-2022-facts-and-figures-latin-america-and-caribbean.

18 https://www.joc.com/article/sourcing-shift-causes-surge-south-american-logistics-investment_20230925.html.

19 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.AIR.GOOD.MT.K1?end=2021&locations=MX-CL-BR-ZJ-AR-CO-CR-Z4-8S-ZQ&start=1970&view=chart.

20 https://www.faa.gov/about/initiatives/iasa/iasa-program-results.