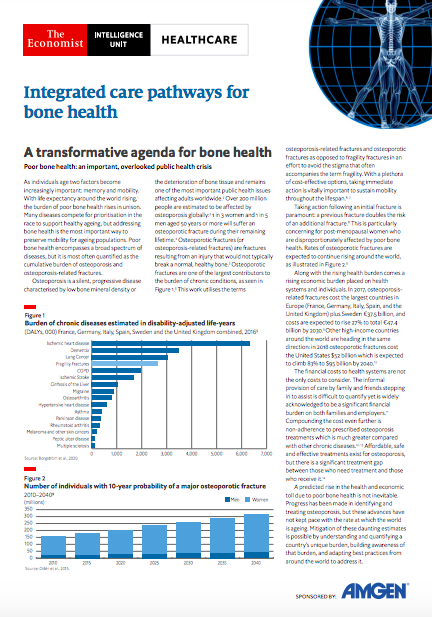

As individuals age two factors become increasingly important: memory and mobility. With life expectancy around the world rising, the burden of poor bone health rises in unison. Many diseases compete for prioritisation in the race to support healthy ageing, but addressing bone health is the most important way to preserve mobility for ageing populations. Poor bone health encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases, but it is most often quantified as the cumulative burden of osteoporosis and osteoporosis-related fractures.

Osteoporosis is a silent, progressive disease characterised by low bone mineral density or the deterioration of bone tissue and remains one of the most important public health issues affecting adults worldwide. Over 200 million people are estimated to be affected by osteoporosis globally: 1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men aged 50 years or more will suffer an osteoporotic fracture during their remaining lifetime. Osteoporotic fractures (or osteoporosis-related fractures) are fractures resulting from an injury that would not typically break a normal, healthy bone. Osteoporotic fractures are one of the largest contributors to the burden of chronic conditions. This work utilises the terms osteoporosis-related fractures and osteoporotic fractures as opposed to fragility fractures in an effort to avoid the stigma that often accompanies the term fragility. With a plethora of cost-effective options, taking immediate action is vitally important to sustain mobility throughout the lifespan.

Taking action following an initial fracture is paramount: a previous fracture doubles the risk of an additional fracture. This is particularly concerning for post-menopausal women who are disproportionately affected by poor bone health. Rates of osteoporotic fractures are expected to continue rising around the world.

Along with the rising health burden comes a rising economic burden placed on health systems and individuals. In 2017, osteoporosis-related fractures cost the largest countries in Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom) plus Sweden €37.5 billion, and costs are expected to rise 27% to total €47.4 billion by 2030.5 Other high-income countries around the world are heading in the same direction: in 2018 osteoporotic fractures cost the United States $52 billion which is expected to climb 83% to $95 billion by 2040.

The financial costs to health systems are not the only costs to consider. The informal provision of care by family and friends stepping in to assist is difficult to quantify yet is widely acknowledged to be a significant financial burden on both families and employers. Compounding the cost even further is non-adherence to prescribed osteoporosis treatments which is much greater compared with other chronic diseases. Affordable, safe and effective treatments exist for osteoporosis, but there is a significant treatment gap between those who need treatment and those who receive it.

A predicted rise in the health and economic toll due to poor bone health is not inevitable. Progress has been made in identifying and treating osteoporosis, but these advances have not kept pace with the rate at which the world is ageing. Mitigation of these daunting estimates is possible by understanding and quantifying a country’s unique burden, building awareness of that burden, and adapting best practices from around the world to address it.

Integrated care pathways: critical to improving bone health

An integrated care pathway is an important tool for unifying the disparate aspects of care for bone health. The pathway encompasses the integration of:

- primary and secondary care: a lifespan approach

- improvements in the co-ordination and comprehensiveness of care delivery and service offerings

- pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches to improve bone health outcomes

- social determinants of health when designing strategies to improve bone health

Though countries around the world will inevitably develop pathways specifically tailored to address their individual needs, the factors listed above are critical to each step. The progression of the pathway requires both primary and secondary care and broadly includes primary prevention (prevention of an osteoporosis-related fracture), care for the initial fracture, secondary prevention (prevention of an additional osteoporotic fracture) and care for the additional fracture. Development of an integrated care pathway for bone health aligns with the strategy of the World Health Organization (WHO) Decade of Healthy Ageing 2021-203015 which brings together stakeholders from governments, academia, the private sector and civil society to create targeted policy recommendations which can be adapted to address a country’s specific bone health needs.

Reducing the health and societal burden of poor bone health is possible through a unified effort that creates an environment where bone health is recognised as an urgent priority. Prevention strategies, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, and co-ordinated care programmes are available in a myriad of modalities. These valuable components must now be woven into an integrated care pathway for bone health to address skeletal health throughout the lifespan.

Global Briefing Paper:

Country Briefing Papers: