There has been no long-term success in tackling rising obesity levels in adults or children. According to the World Health Organisation nearly 40% of the world’s adult population is overweight and 13% obese. We know this increases the risk of dying prematurely.

Whilst many elements impact people’s ability to manage their weight, what we eat and our physical activity levels are determining factors for obesity. People wrongly assume obesity is caused by gluttony; it is not. It occurs because most of us are eating a little bit too much every day and not doing sufficient physical activity to achieve a good energy balance. One way of helping the public to make decisions about what to eat and drink is to provide nutritional labelling with food, but we know people find current food-labelling systems, including “traffic light” labelling confusing and too complicated. For example, what does it actually mean to eat a sandwich containing 650 kilocalories (calories)? Is that good or bad?

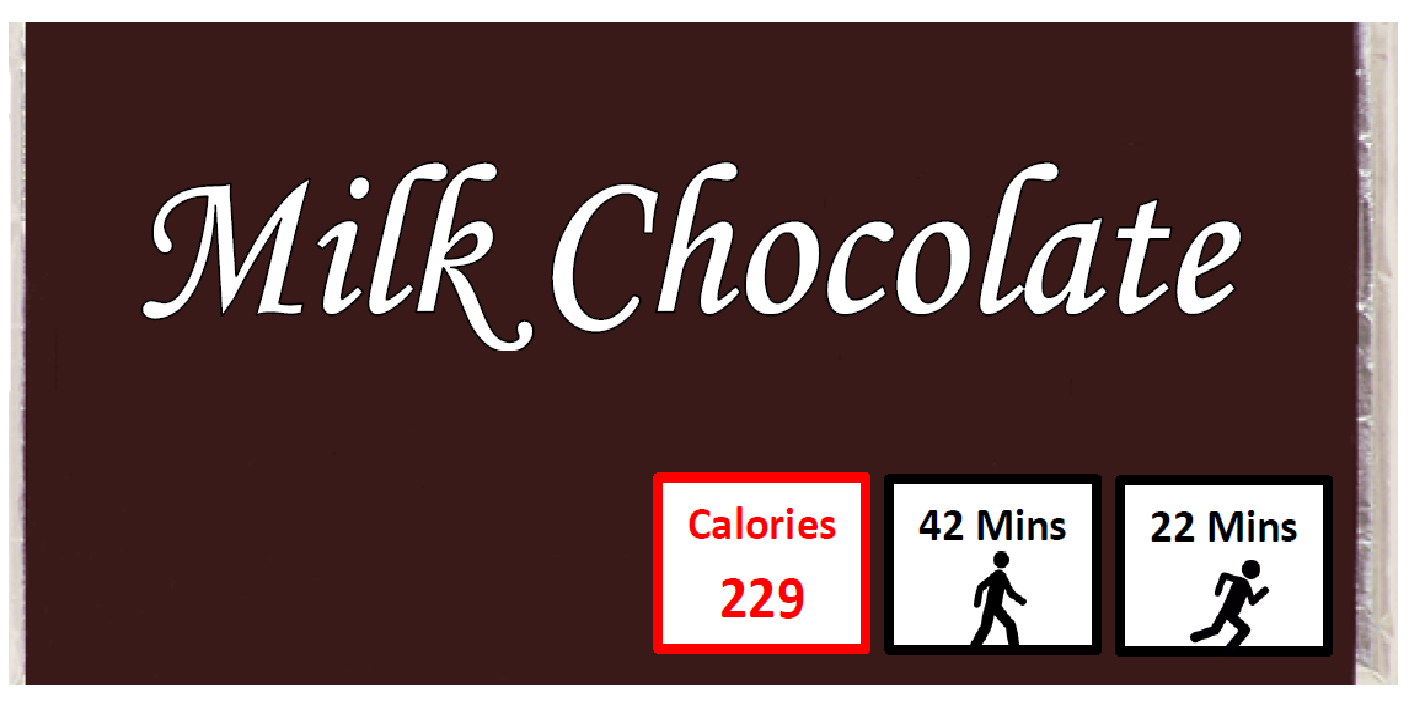

An alternative to current food labelling is an approach called physical activity calorie equivalent (PACE) food labelling. PACE labelling aims to educate consumers about the amount of physical activity (usually running or walking) required to expend the calories in food and drinks. For example, “this chocolate bar will take 95 minutes of running to burn off”, or “this pizza will take 2 hours of walking to burn off”. PACE labelling is based on simple symbols that provide context that tells you what the calories mean.

Images courtesy of Amanda Daley

So should PACE labelling be introduced on all food packaging, including menus in restaurants, and how likely is it to make a difference to our health? We recently analysed all studies around the world that had assessed the impact of PACE labelling on people’s selection and consumption of food and drinks.

We found that when PACE labelling was displayed next to food or on menus it reduced selection by about 65 calories per eating occasion. If we eat three meals per day that would be a reduction of around 200 calories per day. Over a month that could be up to 6,000 calories less (about 1.7 kg in weight).

Our research team also conducted a study where we tried to stop people gaining weight at Christmas. We gave one group PACE information for commonly consumed foods at Christmas, (e.g. cakes, mince pies, crisps, peanuts, wine, fizzy drinks etc), and compared their weight after Christmas with the weight of a group who did not get the PACE information. Those who received the PACE information weighed less than those who didn’t. This seemed to be because the PACE information group consciously tried to restrain their eating as they were shocked by how much physical activity it would take to burn the foods off. PACE labelling also has the potential to simultaneously nudge people to do more physical activity every day. This is important because most people are not doing enough physical activity on a daily basis, which increases the risk having a stroke or heart attack, type 2 diabetes and some cancers.

There has been some criticism from the food industry about PACE labelling: that there isn’t enough evidence that it works, it’s too drastic and it promotes physical activity as a punishment. But if we don’t give the public the raw facts how can we expect them to make healthy choices? People may ignore PACE labelling but let’s at least give them a chance by providing information in a clear, easily-digestible way. Overall, studies suggest that PACE labelling has some promise of improving health outcomes, but we need the food industry to join the debate. It needs to be tested in restaurants, fast food outlets, supermarkets and coffee shops if we are to understand its potential impact on food purchasing and consumption.

One of the criticisms of PACE labelling is that not all calories are equal; 100 calories of vegetables provide better nutrition than 100 calories of chocolate. Of course, I would agree with this. In advocating PACE labelling I am not suggesting the principles of healthy eating are abandoned. Current food labelling has had a limited effect on obesity levels so we need to be innovative and think of different approaches, otherwise nothing will change. If we can get people to eat a bit less and do a bit more physical activity this would save thousands of lives. It’s time to think outside of the box, and PACE labelling has shown some potential to be what we are looking for.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Economist Group or any of its affiliates. The Economist Group cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this article or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in the article.

This publication presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.