By Kate Vyborny, Erica Field and Hana Zahir

Over the last half century, there has been substantial progress in legal reform for women’s rights, with some estimates suggesting that half the laws worldwide curtailing women’s rights have been removed. But women’s rights are often violated in practice: the laws on the books are often substantially more progressive than what happens in reality.

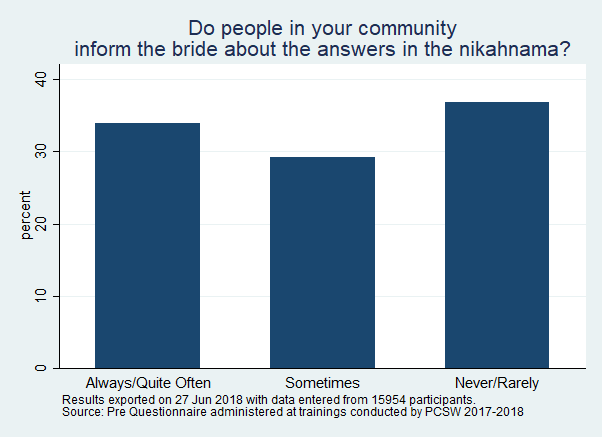

In theory, women’s rights are a crucial part of Pakistan’s marriage laws both in longstanding legislation and 2015 legal reforms. Under current laws, forced or underage marriage is illegal, and the bride and groom must both freely consent to all the terms of the marriage contract, a legally binding agreement that specifies issues ranging from divorce rights to financial terms. But, in practice, most brides aren’t told about the content of the contract they are signing. Consent without this knowledge isn’t full consent.

The Punjab Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW), a government body, launched an initiative in 2017 to start to address this by training the officials who conduct and register marriages in the region. Punjab, a province of over 100m people, has over 40,000 marriage registrars; currently, almost half have received training through this programme. In collaboration with the PCSW and the Oxford Policy Management’s Economic Development and Institutions project (funded with UK aid from the UK government) and J-PAL Governance Initiative, we assessed progress towards informed consent for marriage, education, regulation and further ramifications.

Marriage registrars participate in PCSW’s training. Photo credit: PCSW

Regulation and ramification

The position of registrar is commonly held by an imam. There is no formal qualification mandated for this position. In our baseline survey of approximately 20,000 registrars (which PCSW are using in their advocacy), we found that the majority offer critical advice to families—such as whether to grant the bride the right of divorce in the contract—but 90% of registrars hadn’t received any training for this crucial role. They were unaware of many basic details pertaining to family law, such as the minimum age for marriage or the requirement of informed consent, not that they could theoretically be punished for a violation. We observed that in 57% of cases the bride’s ID card was missing—meaning the registrar did not verify whether they were underage.

Impact of training

Vitally, the PCSW’s project increased the proportion of registrars who intended to explain details of the marriage contract and ensure that the bride understands all contract terms before giving her consent. Similarly, we analysed 14,000 marriage contracts that were completed before and after the training. We found that the training reduced by over a third the number of incidents in which registrars illegally crossed out the bride’s option to initiate divorce instead of asking the couple to decide on this option.

Furthermore, the PCSW is using the findings to advocate for a more gender progressive marriage policy. Some of the PCSW’s proposals include:

- a directive for registrars to counsel both bride and groom on the meaning and implications of the contract;

- obligatory checks of age documentation; and

- raising the legal minimum age of brides from 16 to 18, which means an equal age of consent for the bride and groom.

Pakistan’s Council on Islamic Ideology has already announced a review of the marriage contract form. It is considering simplifying the terms and conditions of the contract, and making it more difficult for marriage registrars to illegally override women’s divorce rights.

The way ahead

In the next steps of the study, we will survey women recently married by newly trained registrars to see if this led to more favourable contract terms for the bride, and also evaluate whether they understand the contract they signed by comparing their survey responses on contract terms to the actual contracts. We also plan to test registrars’ memory of what they learned—to assess any need for follow-up training.

The better the education and training that registrars receive, the better guidance they will be able to give families. This successful legal change could impact the lives of the 50m women of Punjab, and serve as a model for legislative changes in other provinces.

Changing the law to enhance women’s rights is important—but it is only the first step. To make reforms work in practice, government officials, influential community members, families and women themselves must be informed of their rights. The PCSW’s initiative and our study will boost understanding of how education and awareness campaigns can lead to the fulfilment of women’s rights in practice, not just in theory.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (EIU) or any other member of The Economist Group. The Economist Group (including the EIU) cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this article or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in the article.