During the recent climate negotiations in Paris, the EU, Sweden and the G7 nations jointly pledged to raise at least US$10bn for renewable-energy expansion in Africa over the next five years as part of the Africa Renewable Energy Initiative. This is clearly good news, but it must be spent wisely if it is to fund transformational change.

This sum of money might seem like small change for Western multinational energy companies that raise billions of euros in profits every year. It might also seem logical that big money should be spent on big infrastructure projects that international power developers and operators are familiar with and are good at.

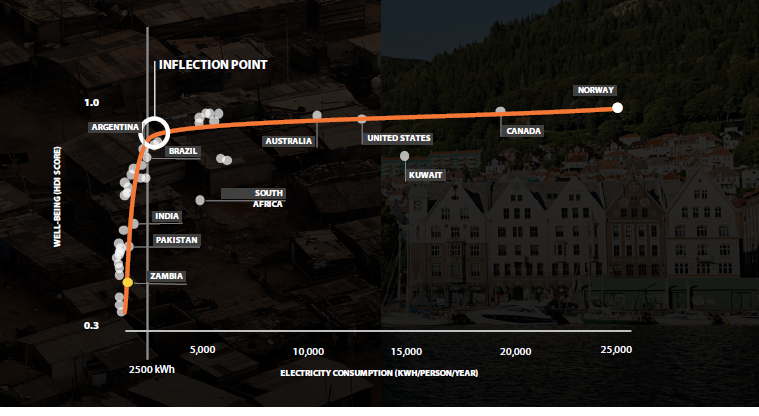

However, the most radical improvements in the Human Development Index (HDI) are seen at energy consumption levels around 10% that of many OECD countries (see chart below). Hence, if the objective of this new US$10bn is to improve lives, livelihoods and overall well-being, what is needed is investments which support small producers rather than a small number of investments in huge power producers.

Source: Power for All, The Energy Access Imperative, June 2014

Historically, infrastructure projects in Africa have run transmission lines over the heads of, rather than to, Africa’s citizens. On the one hand, it was believed that big industry offered big economic opportunities, but on the other, it was assumed that the overwhelmingly poor population of the continent wouldn’t be willing or able to pay for energy anyway. This is why, after 60 years of development assistance, over 600m sub-Saharan Africans still lack access to any kind of modern energy today, and why the International Energy Agency predicts even more may well lack access in the future, as population growth outstrips infrastructure expansion.

However, we are in a period of rapid change and a new breed of entrepreneurs are flipping traditional energy delivery models on their head and showing assumptions about people living in poverty to be completely misguided. Businesses like the Kenyan solar-power company M-Kopa, which sells 15,000 new small solar home systems in Africa per month, provide energy that actually saves their customers money in the long run and improves their lives at the same time by powering lighting, fans, mobile phone charging, entertainment and even refrigeration.

They understand that everyone, no matter how poor, is willing to pay for things that improve their lives. And when you have no electricity at all, it is the first small amount of energy access that makes the most radical improvement in overall quality of life. Astonishingly, governments and large energy producers have failed to grasp this before.

The M-Kopas of the world are also delivering jobs and have the potential to be revolutionary if given the chance. Indeed, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that the energy access space can deliver 4m jobs globally by 2030. In another analysis, the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that over 500,000 jobs can be created by the off-grid lighting industry in West Africa alone. This is significantly more employment than would be possible per megawatt than conventional large-scale fossil fuel-burning power plants could ever offer.

What is encouraging is that donors are slowly getting on board with this reality. Now, rather than offering tediously slow direct incubation support and concessional finance to individual firms, they need to support the construction of an environment where a groundswell of decentralised energy companies can prosper. We need policy and regulatory reform, minimal currency exchange risk, consumer and political awareness, product quality assurance (cheap knock-off products are already seriously affecting trust in this burgeoning market), and import tariff reform. If implemented, we could quickly and meaningfully improve both business and lives across Africa.

Doing this would also encourage skittish private-sector financiers to come out of the shadows and begin talking with these entrepreneurs. The world is awash with cheap credit, but in the energy space at the moment, corporate finance is much more willing to finance bankrupt African utilities than new small and medium-sized energy companies whose products are proving popular.

If spent wisely on learning how to aggregate smaller projects, providing loan guarantees and generally reducing the risk associated with decentralised energy service companies, this new US$10bn could truly revolutionise energy in Africa by delivering empowerment rather than just power.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (EIU) or any other member of The Economist Group. The Economist Group (including the EIU) cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this article or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in the article.