Zoe Tabary, Economist Intelligence Unit: How many people live in slums and where are slums most concentrated?

Alfredo Brillembourg, U-TT: Based on the most recent estimates, almost 900m people worldwide live in slums, defined by UN-HABITAT (the UN's Human Settlements Programme) as a group of individuals living in an urban area lacking at least one of the following:

-housing that protects against extreme climate conditions;

-sufficient living space (no more than three people sharing the same room);

-access to safe water at an affordable price;

-access to adequate sanitation;

-security of tenure that prevents forced evictions.

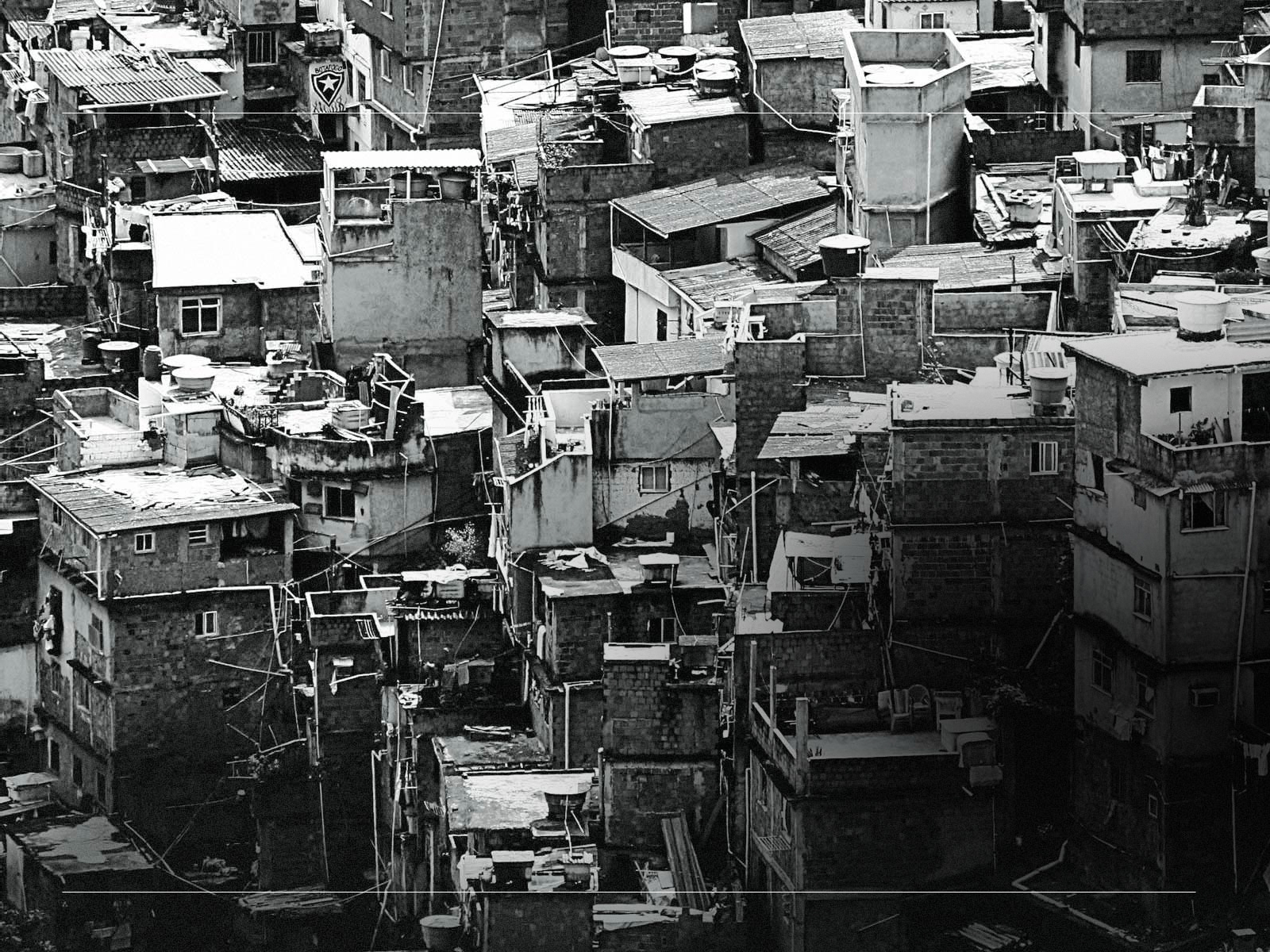

Because of constraints in formal housing in a context of rapid urbanisation, an increasing number of people are resorting to slum settlements on the fringes of the world’s megacities such as Caracas (Venezuela), Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) or Nairobi (Kenya). Slums are primarily concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America.

Could you describe the living conditions in slums?

While slum dwellers are incredibly resourceful when dealing with scarce resources, living conditions are generally tough. Many informal settlements are overpopulated and offer poor access to health, sanitation and education services, as well as low social mobility.

At the same time, there are some variations. In Latin America, informal housing is often built of more robust materials such as concrete, which make for better living conditions. In Asia and Africa, however, informal settlements are frequently constructed out of less resilient materials, leaving inhabitants more vulnerable to natural disasters and other structural threats.

What is "slum upgrading" and why are some local and national governments pursuing it?

The UN predicts that the number of people living in slums worldwide may double by 2050, meaning that policymakers will need to plan for ever-denser urban populations. A number of governments are resorting to "slum upgrading", a strategy focused on lifting slum dwellers out of poverty by both retrofitting vital infrastructure in informal settlements, as well as building better-quality housing in situ that empowers citizens and prevents unnecessary displacement.

The Brazilian government, for example, launched a programme called favela-bairro (slum to neighbourhood) in the slums of Rio de Janeiro in the 1990s. Funded by the Inter-American Development Bank, the programme sought to integrate slums into the fabric of the city through infrastructure upgrading (for example by building water and sewage systems, stairs in houses, and funiculars to connect hills). It was very successful, and involved 253,000 residents in 73 communities.

Similar initiatives are also being implemented around the world, as exemplified by the work of Slum Dwellers International, a transnational network of community-based organisations dedicated to improving the living conditions of slum dwellers and ensuring that these populations gain recognition as equal partners with governments in the creation of inclusive cities.

What lessons can cities learn from slums, and from slum upgrading in particular?

In a way, slums are areas of high sustainability—they use less water and electricity, for example. There is also a stronger sense of community and solidarity than in big cities in general, which are much more anonymous. Slum dwellers are particularly entrepreneurial, with families converting their ground floor into a soup kitchen or a school. Policymakers in developed cities should learn to listen to citizens rather than adopt a top-down approach to planning—a core component of the "slum upgrading" method.

This interview is part of a series managed by The Economist Intelligence Unit for AkzoNobel.