From lifespan to healthspan for all: closing the gap between healthy ageing, women’s health and broader inclusivity

By Emi Michael and Amanda Stucke

This week, against the backdrop of the Milan Longevity Summit (taking place March 14th-27th), we reflect on what we’ve learned through our recent work on the unique nuances and opportunities in this field of longevity and healthy ageing.

When we think about longevity, we might refer to the increasing number of candles on our birthday cakes. Yet a more nuanced reality sheds light on reasons certain groups of people might not be so hasty to celebrate. In many countries large disparities in life expectancy within and between populations exist. For example, in the UK healthy life expectancy at birth is 19 years fewer for women and 18 years fewer for men between the most deprived and least deprived areas.1

Figure 1

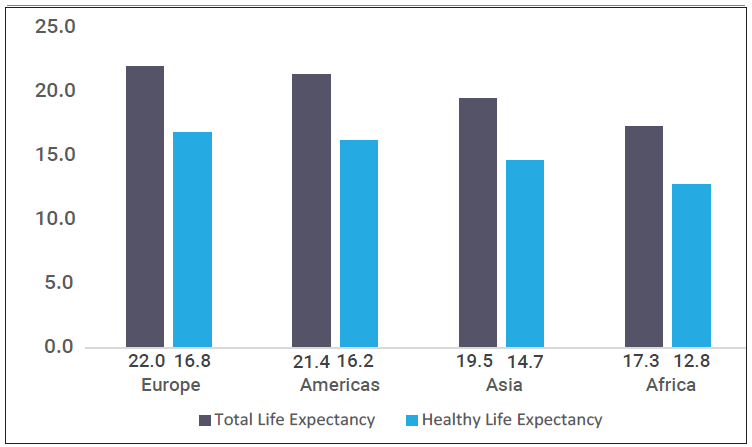

Total vs healthy life expectancy at age 60 by region in 2019

Source: UN DESA. Authors' calculations based on data from WHO Global Health

Observatory. Available at: https://www.who.int/data/gho

Defining lifespan versus healthspan

While both average life expectancy and healthy life expectancy have increased over recent years, healthy life expectancy is increasing more slowly, and stark variations between them exist across regions (See fig. 1).2

At first glance, the statistics seem promising. People are living longer than ever before, with life expectancy steadily climbing over the decades, in large part thanks to public health and medical innovation. However, a crucial divergence exists—the gap between how long we live and how long we live in good health. And here lies the crux of the matter: while we're extending lifespans, we're not necessarily extending the years spent in good health, often referred to as healthspan. This dichotomy raises profound questions about how to ensure quality of life across the lifespan, particularly in our later years, not to mention the gendered experiences that shape the ageing process.

The disproportionate impact on women across the life course

Notably, women mostly have a higher life expectancy than men. In 2021, this difference amounted to a five-year gap in global life expectancy (73.8 compared with 68.4).3 However, most of this higher life expectancy means living longer with some disability. Understanding the role of exposure to risk factors such as tobacco and alcohol use, along with unhealthy diets, offers some explanation. For example, in many developed nations, men are more likely to die from cancer, heart and other diseases after the age of 65, while women often experience higher rates of chronic conditions that are less likely to result in early death, such as arthritis and depression.4

Nowhere is this inequality more apparent than in the experiences of women as they age. The life course of a woman is often characterised by multifaceted responsibilities that can impact her health and well-being in profound ways. From leaving the workforce to bear children to assuming care-giver responsibilities for both children and ageing parents, women navigate a complex web of roles and duties throughout their lives. This juggling act can exact a toll on their health, contributing to a pattern of inequalities in healthy ageing. These negative impacts on women are amplified across other areas of society, highlighted by our research for the Health Inclusivity Index.

“Women play many important roles taking care of the health and well-being of families and communities and [are] an engine of societal development. For their own health and the realisation of their social capital, they deserve all of the care that governments and other entities can offer—but so far they are not getting that support in many places around the world.”

Dr Ana Langer, professor of the practice emerita, Global health and Population Department, T.H. Chan School of Public Health

As parents age and family members require assistance, women often find themselves shouldering the bulk of care-giving duties. It is estimated that up to 81% of care-givers globally, formal and informal, are female, and they may spend as much as 50% more time giving care than males.5 This can lead to increased stress levels, limited time for self-care and disruptions to personal well-being, all of which can impact healthy ageing. Moreover, the phenomenon of the "sandwich generation"—individuals simultaneously caring for both children and ageing parents—is more common among women, exacerbating these challenges.6 Some have even extended this metaphor to call it the “panini generation”, reflecting on how women today are further squeezed in all directions.

Compounding these issues are the gendered patterns of disease in later life. Certain conditions, such as dementia, multiple sclerosis, migraine and stroke disproportionately affect women.7 Over twice as many women have Alzheimer's disease—the most common type of dementia—compared with men.8 The reasons for this gender disparity are multifaceted, stemming from biological, social and environmental factors. Our recent work with the Women’s Brain Project, Sex, gender and the brain: Towards an inclusive research agenda, shows that addressing these inequalities requires a comprehensive understanding of the intersecting forces that shape women's health as they age.

Enter the silver economy…

Enter the silver economy—a burgeoning sector focused on meeting the needs and demands of ageing populations, with a focus on maximising the ability for older people to continue to be valued members of society. From health-care services to leisure activities, the silver economy encompasses a wide array of industries poised to cater to the needs of older adults. The potential economic upside is significant. Our work exploring the Global Longevity Economy Outlook shows that people 50 and older are making unprecedented contributions to economic growth globally, not just for their generation, but for all generations. However, to fully harness the potential of this economic opportunity, it is imperative to address the underlying inequalities that disproportionately affect women.

Taking action: a societal overhaul

Fostering an inclusive and supportive environment for older women in particular is paramount. This includes policies and initiatives that address gender inequalities in healthy ageing that facilitate equal access to services that promote healthy ageing, in addition to opportunities within and outside the silver economy, empowering them to thrive and contribute to society.

Addressing gender inequalities in healthy ageing is critical and also has an economic imperative. Our recent research on Real-world solutions to help facilitate equity in healthy ageing, part of AARP’s Ageing Readiness and Competitiveness series, offers pragmatic innovations and best practices with a focus on what low- and middle-income countries can do to take action. For countries at all economic levels, addressing these challenges cannot happen in a silo—we know from history that a cross-sectoral revamp across financial, social, structural and health systems is required to drive progress.

By recognising and rectifying the unique challenges faced by women as they age, we can unlock the full potential of the silver economy, fostering a society where everyone has the opportunity to age with dignity and grace. It is only through collective action and a commitment to gender equity that we can truly realise the promise of healthy ageing for all.

Join us starting next week at the Milan Longevity Summit (March 14th-27th), where we will join some of the foremost experts in this space to explore the unique interplay between longevity, women, inclusivity and more.

References

1 UK Office for National Statistics. Health state life expectancies by national deprivation deciles, England: 2018 to 2020. 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthinequalities/bulletins/healthstatelifeexpectanciesbyindexofmultipledeprivationimd/2018to2020

2 UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. UN DESA Policy Brief No. 145: On the importance of monitoring inequality in life expectancy. 2022. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-no-145-on-the-importance-of-monitoring-inequality-in-life-expectancy/

3 Our World in Data. Why do women live longer than men? 2023. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/why-do-women-live-longer-than-men#:~:text=Women%20tend%20to%20live%20longer,expectancy%20is%20not%20a%20constant.&text=Women%20tend%20to%20live%20longer%20than%20men.,versus%2068.4%20years%20for%20men.

4 Carmel S. “Health and well-being in late life: Gender differences worldwide”. 2019. Frontiers in Medicine.

5 Sharma N, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. “Gender differences in caregiving among family—caregivers of people with mental illnesses”. World J Psychiatry. 2016.

6 UK Office for National Health Statistics. More than one in four sandwich carers report symptoms of mental ill-health. 2019. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/articles/morethanoneinfoursandwichcarersreportsymptomsofmentalillhealth/2019-01-14#:~:text=Some%20of%20the%20differences%20between,years%20and%2051%25%20are%20women.

7 Economist Impact. Sex, gender and the brain: Towards an inclusive research agenda. 2023. Available from: https://impact.economist.com/perspectives/sites/default/files/womensbrainproject_report_230306.pdf

8 https://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/news/why-women-are-bearing-more-of-the-impact-of-dementia/