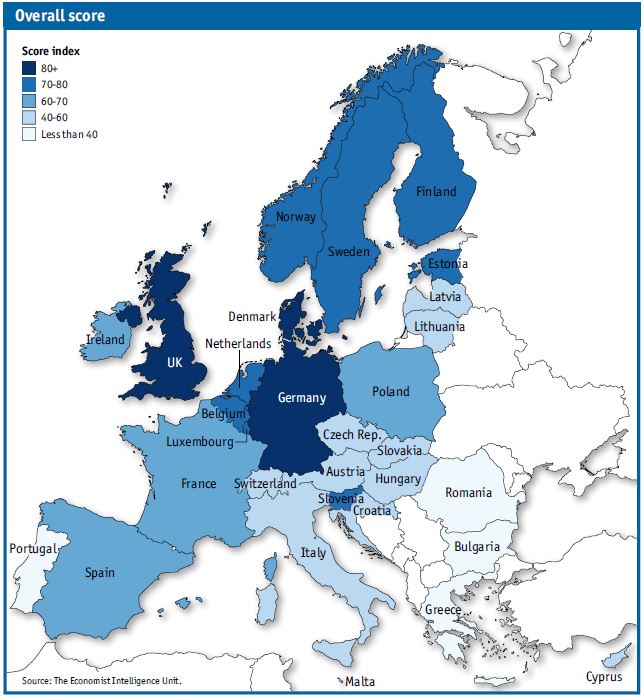

Few diseases are more poorly understood and more subject to stigma and prejudice than mental illness, and few impose the same magnitude of burdens on both the afflicted and society at large. Indeed, mental disease (including substance use disorders) is among the leading disease areas in terms of the global burden of disease, ahead of diabetes, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, for example (see chart 1 below). This has negative economic repercussions: in Europe, for example, the direct and indirect costs of mental illness on GDP are estimated annually at 3% to 4%.

Chart 1: Share of global disease burden, 2015 (disability-adjusted life years, DALYs)

Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 (GBD 2015), GBD Results Tool. Available at: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

Europe faces large "treatment gap" in mental health

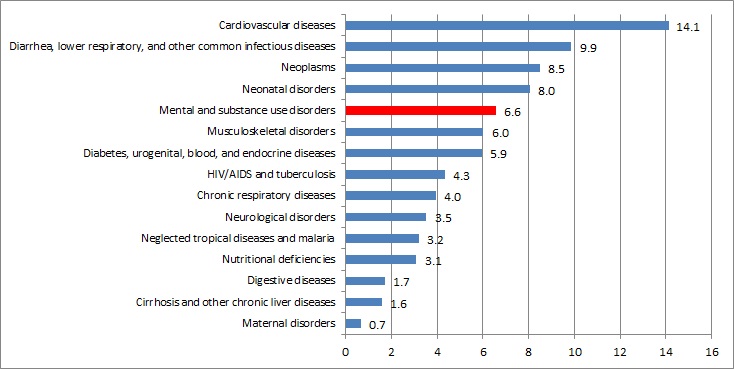

While a consensus has emerged among caregivers, policymakers and patient advocates on the benefits of integrating the affected individuals into society and employment rather than sequestering them in institutions, few countries have come close to realising this ideal. In 2014 research by The Economist Intelligence Unit, commissioned by Janssen, assessed the degree of commitment in 30 European countries—the EU28 plus Switzerland and Norway—to integrating those with mental illness into their communities.

Our study found that only one-quarter of Europeans affected by mental illness get any treatment at all, while just 10% of affected individuals receive “notionally adequate” care. The analysis shows that Germany leads Europe in terms of mental health integration, on the strength of its good healthcare system and generous social welfare provision. Not far behind are the UK and several Nordic states. The weakest countries are largely in Europe’s south-east (see chart 2 below).

Chart 2: Mental Health Integration Index results for Europe

The study found that real investment sets apart countries seriously addressing integration from those creating “Potemkin policies” which are more façade than substance. Overall country scores show a strong correlation with the proportion of GDP spent on mental health.

Moreover, the research cast a spotlight on the limitations—both in terms of availability and comparability—of European data on mental health integration. The Economist Intelligence Unit developed qualitative data on integration efforts in large part because of the absence of quantitative data comparable across the 30 countries under review.

Finally, the research concluded that Europe is only at the start of the journey from institution-based to community-centred care. It found that even deinstitutionalisation is in early stages; in 16 of the 30 countries more individuals continue to receive care in long-stay hospitals or institutions than in the community. In addition, data show that medical services for those with mental illnesses are poorly integrated, and that government-wide policy to coordinate medical, social and employment services is a rarity.

Light and shadow in the UK

The UK ranks second overall in the Mental Health Integration Index for Europe and first in two individual categories: “Environment”, a measure of policies and conditions allowing those with mental illnesses to live a stable home and family life; and “Governance”, a general category including the extent of human-rights protection and of anti-stigma efforts. Our research focused on mental health policy in England and found that English policy towards those with mental illness has seen a steady improvement, supported by a generally supportive political environment. Current policy aims to create a “parity of esteem” between mental and physical health services (that is, giving equal value to mental and physical health).

However, turning aspirations into reality takes time and faces hurdles, including a lack of investment and the structure of government agencies. Evidence of weakness can be seen in the ongoing, substantial treatment gap in mental health care. The UK ranks in eighth place in the Index’s “Access” category, one of the country’s worst results. Mental health trusts have seen their funding drop in recent years. However, cuts in relatively expensive inpatient beds have not been channelled into greater spending on community-based services. There is also a significant shortage in mental health social workers, a situation that could get worse in the wake of the UK's decision to leave the EU.

In 2016 The Economist Intelligence Unit adapted the framework for the European index to the Asia-Pacific region. Its findings can be found here.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (EIU) or any other member of The Economist Group. The Economist Group (including the EIU) cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this article or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in the article.