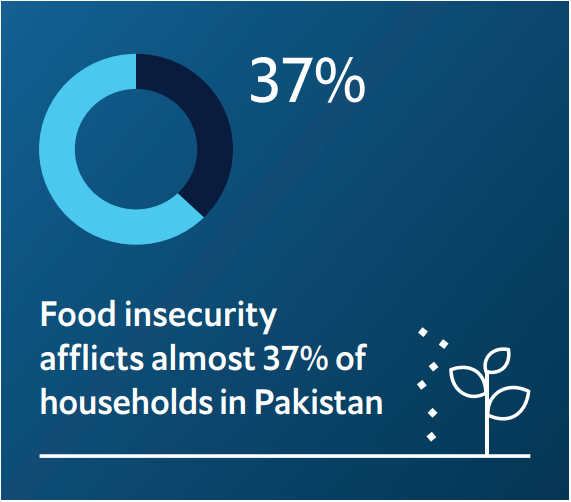

Food insecurity, a condition in which households lack access to adequate food because of limited money or other resources, afflicts almost 37% of households in Pakistan. As a result of this insecurity, malnutrition— when a person’s diet does not contain the right amount of nutrients—is commonplace. About half of adult women in Pakistan suffer from anaemia, over a third of children are stunted, and about 30% of under 5-year-olds are underweight.

Malnutrition is also found in hospitals and other clinical settings in Pakistan and worldwide. It is estimated that, globally, malnutrition affects almost 50% of patients admitted into hospital. And yet only 7% of these are typically diagnosed, leaving millions potentially undiagnosed and untreated, while other patients can develop the condition while in hospital. Clinical malnutrition can lead to the need for high-dependency clinical care, lengthen recovery times, and increase the likelihood of high-risk complications. It contributes to the worsening of both chronic illness and acute disease and infection.

Clinical malnutrition also has consequences for hospitals and the wider health system: increased costs resulting from longer lengths of stays, more intensive clinical care and higher readmission rates can cripple health system administrations. For example, the cost of hospitalization was 24% higher among patients in Singapore who were malnourished compared to those with adequate nourishment, while in Thailand hospital costs increase an average of $158 for those with mild malnutrition to $3,870 for those with severe malnutrition. In Brazil, malnourished patients had hospital stays that were on average seven days longer with up to three times the costs of patients without malnutrition.

There are a variety of nutritional interventions that can reduce malnutrition and improve outcomes. These range from medically tailored meals (also called therapeutic meals), medically tailored groceries and produce prescriptions, through to meal replacements and nutritional supplements of various kinds. Much of the evidence for these interventions come from high-income countries. For example, a US study found that oral nutritional supplements for hospitalised patients shortened length of stay by an average of 2.3 days and reduced the probability of early readmission; consequently, hospital costs were reduced by up to $5,000 per hospital episode.

While a failure to effectively diagnose and manage clinical malnutrition is not unique to Pakistan, the challenge is particularly acute in the country. In this short article, we ask why this is the case, and what might be done to reduce the burden of poor nutritional intake among patients.

A dearth of nutritionists and dietitians

Many factors combine to stifle the development of better nutritional care in Pakistan. The problems begin when the patient enters a healthcare facility, for most patients are not screened for malnutrition upon admission. As a result, many commence their stay facing a hurdle, and more than two thirds of patients with malnutrition decline further during their stay.

If afflicted patients were identified early and provided with a suitable care plan, then complication rates, length of stay, readmission rates, mortality and cost of care would all be reduced. But this requires trained nutritionists and dietitians. Unfortunately, Pakistan is lacking such staff in the hospital setting. “ It is not humanly possible for me to do a malnutrition assessment of every patient,” laments the dietitian Lieutenant Commander Anwar, a practicing dietitian and former President of the Pakistan Nutrition and Dietetic Society, a body that is dedicated to upgrading the professional knowledge of dietitians practicing in Pakistan. “We have very limited staff in hospitals. Some of the hospitals have more dietitians, some of the hospitals have less dietitians, so it is not universal here.”

Often the terms nutritionist and dietitian are used interchangeably. However, the Pakistan Nutrition and Dietetic Society requires a dietitian to have dietetics qualifications and training, whereas a nutritionist does not.As a result, all dietitians are nutritionists, but not all nutritionists are dietitians. The role of registered dietitians and nutritionists is to provide care to patients in a variety of settings; they are responsible for assessing the nutritional needs of patients, providing appropriate diet-related care plans and educating patients and families on diet.

Why the shortage of suitably trained staff? It begins with a lack of appropriate education programs, says Dr. Rubina Hakeem, Principal, RLAK Government College of Home Economics Karachi and founding chairperson of Nutrition Foundation of Pakistan. Colleges of home economics established the profession of dietetics in Pakistan in the 1950s, she says. Many of these colleges continue to run high quality dietetic programmes, producing graduates of home economics with specialisation in nutrition. However, because of the limited supply of graduates from these colleges, many programs have been founded in Pakistan where few, if any, of the faculty has studied or practiced dietetics or clinical nutrition. These programs can vary in the content and quality of education. “That is a very, very concerning area because those new graduates are now a very large number,” she states.

To turn this around, the Pakistan Nutrition and Dietetic Society is encouraging hospitals to make a conscious approach to hiring nutritionist specialists. “Our society is actually networking with all hospital managements to hire only registered dietitians in the hospital so that medical nutrition therapy can be successful,” says Lt. Cdr. Anwar. Subsequently, the Government of Pakistan is now developing accreditation for nutritionists and dietitians. Doing this will help ensure there are standards of practices for these professionals, that there is regulation set in place for what they do and how they do it. It will also, it is hoped, lead to better dietary practices in clinical settings.

Getting trained dietitians into hospitals and part of multidisciplinary teams is a critical task. The evidence suggests that a multidisciplinary approach to care improves outcomes, and that teams should ideally be comprised of nurses, pharmacists, physicians and, of course, dieticians, who would work together to provide screening, develop strategies to educate patients and develop an evidence-based care plan. The team would also be a tether to primary care, creating a link for longitudinal care plan. Such teams, with nutritionists or dieticians onboard, are rare in Pakistan. But while it will require some patience and work, Lt. Cdr. Anwar is somewhat hopeful. “Hospitals acknowledge that this is the need of the hour; that they have to have multidisciplinary teams in the hospital.”

Getting patients to eat more

The simplest, safest, and cheapest way to provide nutritional care and support is to get the patient to eat more of the food that is given to them. But a recent survey in Pakistani hospitals concluded that patients were generally unhappy with the quality of hospital food—they were often not inclined to eat what they were given. This is not unique to Pakistan. A British survey showed that average food intake is 75% less than what is recommended and that between 30-50% of hospital food is wasted, particularly among the elderly population. The reasons for such wastage varied from the menu not taking into account cultural differences, to food being unappetizing, or meals simply being served at inconvenient times.

It has been suggested that a solution to this aversion to hospital food in Pakistan may be to allow patients to provide immediate comments on their meals, therefore creating a continuous cycle of feedback. This could lead to a demand for more frequent, smaller meals, or a broader range of more appetizing dishes; anything to encourage the consumption of nutritious meals. But Dr. Achakzai notes that, “in the public sector one of the barriers is that the tertiary care hospitals are heavily crowded. When a hospital is heavily crowded you cannot, for example, calculate each and every individual’s foodstuffs or the nutrition they need.”

An approach that can help circumnavigate this lack of time and resource is the use of oral nutritional supplements. These have been found to lead to a reduction in length of hospital stays, and lower bed-day and complication costs, when compared to patients who receive no supplementation. Pakistan has included supplementation in its multi-sectoral nutrition strategy, which began in 2018 and spans to 2025. This strategy includes the provision of balanced energy protein supplementation for key groups and multiple micronutrient supplements for a variety of populations.

An approach that can help circumnavigate this lack of time and resource is the use of oral nutritional supplements. These have been found to lead to a reduction in length of hospital stays, and lower bed-day and complication costs, when compared to patients who receive no supplementation. Pakistan has included supplementation in its multi-sectoral nutrition strategy, which began in 2018 and spans to 2025. This strategy includes the provision of balanced energy protein supplementation for key groups and multiple micronutrient supplements for a variety of populations.

“Nutrition is not the priority.”

One of the reasons why people are often unwilling to pay for nutritional interventions is because it is simply not seen as a priority in Pakistan—neither by the public nor professionals. Indeed, the very concept of nutrition itself is nebulous among the general population and those who work in healthcare. As such, there is little recognition of its importance or even its role in hospitals. “You’ll be surprised to know that other professionals are [working] in place of dieticians and who are doing the job of a dietitian,” shares Lt. Cdr. Anwar. She adds, “pharmacists are hired, therapists are hired. They are working as a dietitian in some of the hospitals. So, you can imagine then what is the state of policy in nutrition.”

A lack of nutritional knowledge among clinical staff in Pakistan is a persistent issue. “[Hospitals] are not very receptive towards a dietitian,” laments Lt. Cdr. Anwar. “Those practitioners who are locally educated in Pakistan, they don’t support [dietitians]. They want to prescribe their own diet…and they tell the dietitian to only make the menu for it, that’s it.” There are some hospitals who do focus on nutrition—about 10-15% Lt. Cdr. Anwar estimates—and those hospitals are getting results. “They have shorter hospital stays, they have seen the overall benefits,” says Anwar. She also adds there are fewer readmissions if discharged patients’ nutritional status is good.

Compounding this issue of poor awareness of nutrition in hospital is a lack of concern about nutrition in the wider population of Pakistan. “Nutrition is not the priority for Pakistanis,” says Lt. Cdr. Anwar. Dr. Achkazai proposes that the government should prioritize educating the public. A mass media campaign focussing on educating the public on how important clinical nutrition is would empower them to ask for the care and services they need when in hospital. Dr. Hakeem concurs with this approach and recommends that subject matter experts assist with the education campaign. “If people who are not qualified and trained [lead the education], the public cannot understand the problem.”

A fragmented policy landscape

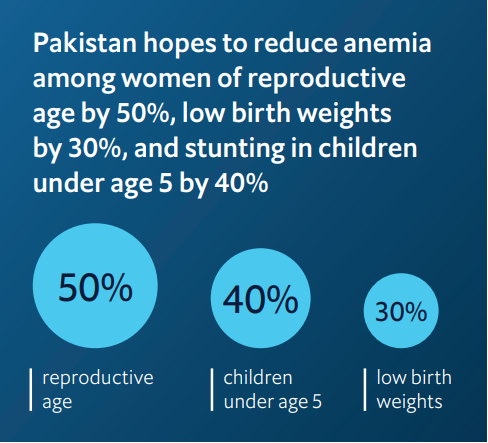

Pakistan’s overarching nutrition strategy looks to pursue a multi-sectoral approach that aligns with provincial and national goals. The strategy aims to create economies of scale in the areas of procurement, capacity building and logistics. As a result of its multi-pronged strategy, Pakistan hopes to reduce anemia among women of reproductive age by 50%, low birth weights by 30%, and stunting in children under age 5 by 40%. They also hope to stabilize the rate of overweight children.

But there remain big gaps in the plan, including on clinical malnutrition. And there is little on the monitoring and evaluation of whether the strategies are effective and if the desired outcomes are being met. Dr. Achakzai acknowledges this gap. “We have a strategy on nutrition in emergencies. We have a strategy for micronutrient deficiencies. But clinical nutrition, as policy measures, so far we have not addressed that.” But it’s not only policies which are needed, but regulation of the sector too.

“There is no regulatory body who can regulate the practice of dietitians,” points out Lt. Cdr. Anwar. It was because of this failure to regulate that she and several colleagues formed the Pakistan Nutrition and Dietetics Society in 2003. Formation of the Society has also brought an awareness of the subject matter among policymakers. It has been a long, hard slog, but the work of the society has led to a growing awareness that a more concerted clinical nutrition policy effort is required.

However, since Pakistan’s healthcare system is not solely governed by the centre, reforming and refining elements of the health system can be arduous tasks that require lengthy negotiations and many compromises. “Hospitals come under the provincial government domain, so in Pakistan the healthcare services are decentralized to the provinces and we cannot interfere in what policies they have, what SOPs (standard operating procedures) they adopt,” says Dr. Achkazai. “But regulation is the domain of the federal government,” he shares, and federal government officials are aware that a paradigm shift related to clinical nutrition needs to occur.

Dr. Hakeem concurs, but also adds that a lack of resourcing contributes to being a blocker to regulation. “There is no national level guideline about clinical nutrition because not even all the hospitals are bound to have a dietitian or nutritionist.” This suggests that regulations will only follow when there is a critical mass of appropriately qualified nutritionists and dietitians to regulate.

Stepping up to the plate: the future of clinical nutrition in Pakistan

While Pakistan’s multi-sectoral Nutrition Strategy is laudable, it will require a concerted effort to make a meaningful impact on patient’s lives. There is also a need to update and revise the strategy for it to remain relevant, and to take into account the findings of the National Nutrition Survey 2018. The strongest lever the national government has is over regulation. Investing in improving the quality and quantity of nutritionists seems like the most likely path to success, as a stronger profession will be able to advocate and support the development of national guidelines, and then through them influence regional government and other agencies.

Lt. Cdr. Anwar looks to Malaysia. “Recently, their council has been approved by the government. They have struggled a lot to get them through, so we are working with their dietician association.” She also points to Taiwan and Philippines, and the fact that they regulate dietitians. She is lobbying the Pakistani government to do the same.

Once regulation has created a strong profession, practitioners will be able to support the establishment of high-quality national guidelines. Having worked in Saudi Arabia, Dr. Hakeem thinks there are some learnings to be had from her experience there. “I know that they have a centralized guideline. They have a manual for hospital nutrition and that you distribute it to all the hospitals, and it has major guidelines on what type of diet should be given in which conditions” Dr Achkazai agrees that “there should be a policy guideline”, and there “should be a clinical dietitian to give accurate or appropriate advice to the patient.”

While waiting for formal regulation, Dr. Hakeem states that dietitians are coming together in less formal ways, using Facebook and WhatsApp groups, for example, to expand their knowledge and community of practice and doing webinars for free. Such activities show an increasing pride in, and advocacy of, nutrition-related professions in Pakistan. It may be that this pressure from below causes the government to act. Patients in Pakistan’s hospitals will be hoping that this is the case.