According to executives polled by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in the run-up to Davos, the healthcare sector is best placed to benefit from the merging of physical, digital and biological systems in the wake of the Fourth Industrial Revolution; however, the sector is among the least well prepared for this megatrend, the survey also found.

Many middle-income countries (MICs) such as Brazil, China and India could benefit enormously from reaping the new opportunities for healthcare provided by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, but they also need to overcome major challenges. The WEF officially launched The Future of Health as one of its global challenges at this year's meeting, in order to boost the global response to the new challenges and opportunities facing healthcare. During the launch press conference, Arif Masood Naqvi, the founder and group chief executive of The Abraaj Group, a private equity investing firm operating in many MICs, highlighted that the lack of high-quality healthcare in many MICs endangered growth in these markets. And Arnaud Bernaert, head of Global Health and Healthcare Industries at the WEF, stressed the need to focus more on prevention and the design of smarter cities that are better equipped to deal with healthcare challenges, such as population ageing and the spread of pandemics.

Rapid urbanisation in middle-income countries

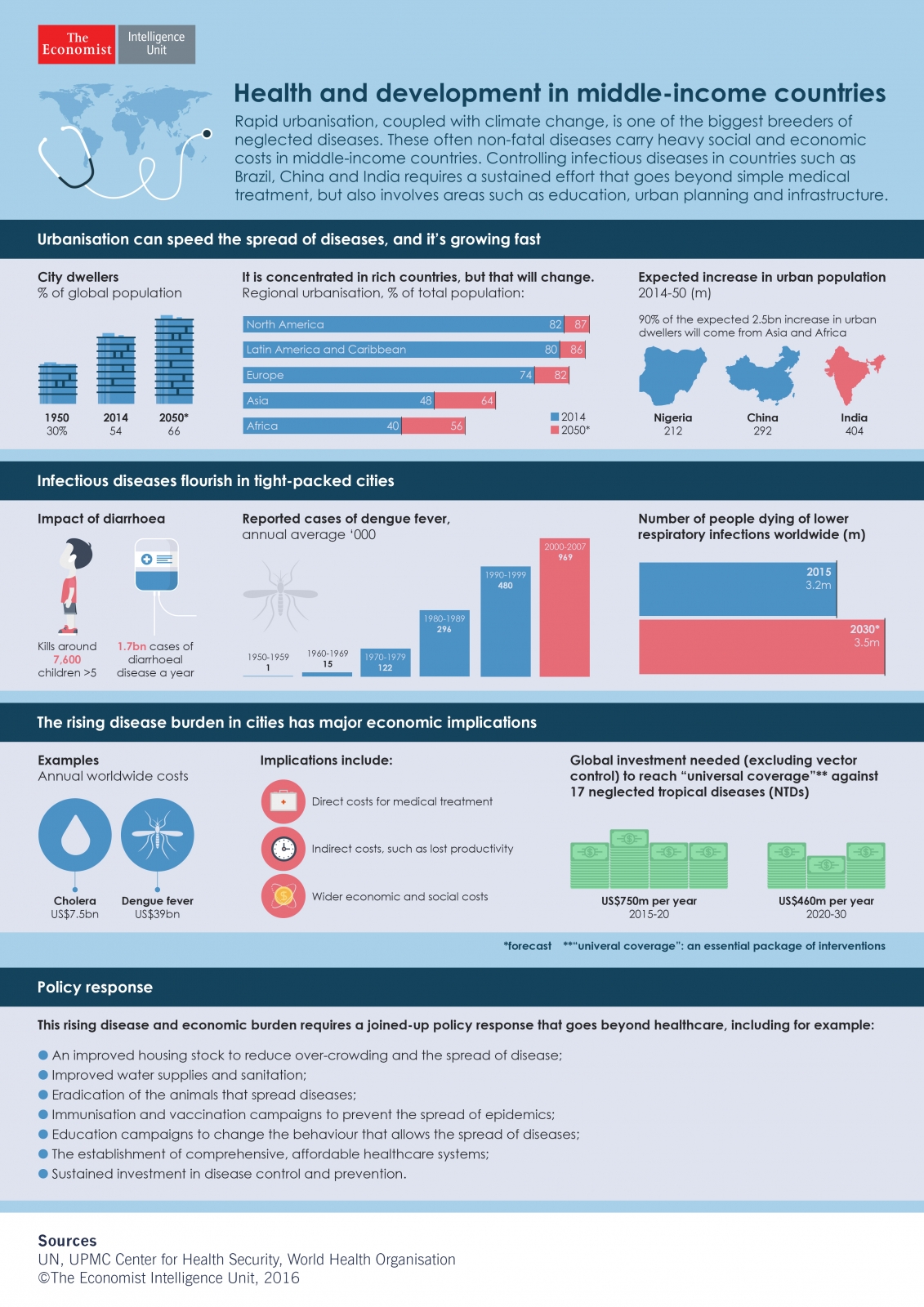

The call for more determined action on global health at Davos could not have been timelier: the outbreak and spread of the Zika virus—transmitted by the bite of mosquitoes—in the Americas has highlighted the risk of pandemics spreading rapidly. This risk will likely escalate, with more than half of the world’s population now city dwellers—a share the UN expects to rise to two-thirds by 2050. This explosion in urban dwellers threatens to exacerbate problems with a host of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) that are sometimes not fatal but that can still carry very heavy social and economic costs in MICs.

In a recent report on tackling 17 NTDs, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has highlighted that rapid urbanisation, coupled with intensifying climate change, is one of the biggest risk factors contributing to the threat posed by neglected diseases in MICs. “More people now require coverage [against NTDs] in middle-income countries than in low-income ones,” says WHO health economist Christopher Fitzpatrick. This is especially true of the unplanned mega-cities cropping up everywhere from Asia to South America.

Take another mosquito-borne disease such as dengue, for example, which is the fastest-growing tropical disease and among the 17 NTDs highlighted by the WHO. Dengue has been identified as a "disease of the future" by the WHO in light of rapid urbanisation, scarce water supplies and climate change, which will facilitate the spread of mosquito-borne diseases. Some 90% of dengue cases are in poor or middle-income countries, says Dr Raman Velayudhan, who is in charge of dengue control at the WHO. He points out that it now affects more countries than malaria (120 against 96). Crystal Boddie at the UPMC Center for Health Security and her colleagues calculate the global cost of dengue at US$39bn [at purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates] a year, factoring in productivity losses as well as direct medical expenses.

Joined-up policy-making to tackle urban diseases

Prevention of NTDs can be more cost-effective than treatment in the long term. Disease control in the new mega-cities means much more than building a few new hospitals. “Although difficult to achieve in practice, mosquito eradication would be much more cost-effective than simply treating the illnesses,” Ms Boddie explains. However, vector control—while an important part of an overall solution—is not sufficient alone. For dengue for example, there is a growing consensus in the dengue-prevention community that no single intervention will be sufficient to control dengue, but that different approaches, such as vector control and vaccination, complement and enhance one other.

The WHO's Global Strategy for dengue prevention and control (2012–2020) highlights five key pillars: diagnosis and case management; integrated surveillance; vector control; vaccine implementation; and research. As with other NTDs, these approaches complement each other. “There needs to be joined-up and integrated policy-making to tackle these urban diseases,” says Professor Tikki Pang of the National University of Singapore. Integrated policy-making means different government departments work together to improve population health, from diagnostic and immunisation programmes through the health ministry to helping to educate people on disease avoidance measures through the education ministry, to ensuring clean water supplies through the water and sanitation departments.

Better outbreak preparedness through improved surveillance is an important policy response. “Integrated surveillance is crucial to control the disease at source. Unless this is done, dengue will continue its rapid spread across the world through increased international travel and trade,” warns Dr Velayudhan. Although, better use of data and technology is essential for surveillance to be effective, "inadequate governance structures to leverage technology and big data for improving health" remains a major challenge, according to the WEF.

Additionally, the WEF panel highlighted the need for innovative solutions to face global health challenges. And in the case of dengue, big data and technology can make a huge difference in boosting surveillance. For example, in Pakistan’s Sindh province, a new smartphone app uses spatial mapping to identify dengue hotspots.

Technological advancements can also support the roll-out of vaccination campaigns. For example, in a Calcutta slum, mobile phones and GPS data have been used to register residents and raise rates of polio vaccination and decrease incidence of diarrhoea and malaria.

One advisor to the Indian government (who asked not to be named) echoes this point, saying that the failure to link different ministries’ and municipalities’ actions is the country’s biggest weakness in disease prevention. Hospitals located in the big cities are dangerously inaccessible to rural dwellers. She adds that the growing number of slum dwellers in major cities falls outside of formal government healthcare efforts.

Responding to these challenges requires long-term thinking. At the moment, action is often focused on responding to an intense outbreak of a disease. Mr Fitzpatrick from the WHO says that the cost of disease goes well beyond the immediate financial and economic impact of medical treatment and lost productivity. It also has severe social costs that need to be factored into spending decisions. The need is “for a sustained effort and investment,” Mr Fitzpatrick says.

Stronger collaboration can help to translate this vision into reality. Speaking at Davos, Mr Naqvi from the The Abraaj Group highlighted the need for a more alliance-based approach, including private equity investment in MICs, increased "partnership capital" and enhanced collaboration between key stakeholders such as governments, care providers, insurers, industry, financial institutions and philanthropic organisations.

Building smarter cities

Given rapid urbanisation, collaboration needs to be intensified already at the urban-planning stage. For many neglected diseases, such as dengue, most of the affected countries have set up dedicated taskforces to join up eradication efforts. From New Delhi to Singapore, many big cities in MICs have regulations in place to prevent disease spread and cure symptoms, for example severe penalties for allowing mosquitos to breed in puddles of water and gutters.

Professor Pang points out that Singapore, a relatively rich city-state with strong government, can regulate things like urban mosquito control tightly. But in other cities (for example in poorer Asian and Latin American states) the regulations are not effectively implemented and consistently enforced, he adds.

Smart city design is one of the areas where a more integrated approach, coupled with long-term investment, can have a huge impact. Designing cities that are more resilient to outbreaks of NTDs in the context of climate change is crucial. One way to incorporate health into urban planning in "climate-smart cities" is to strengthen service delivery for resilient populations by making health investments that align with urban-planning goals, including for example the integration of essential health care services and interventions; clean water and sanitation services; and vulnerability mapping and other urban-planning tools in order to assess the best locations for new residential and commercial areas.

In practice, smart-city initiatives can make a major difference in disease prevention and control. For example, in Patna in India a pilot programme launched by the Ministry of Health seeks to use Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping to support the expansion of the city’s vaccination programme.

Meanwhile, in Singapore the National Environment Agency (NEA) uses smart mapping for dengue prevention and control efforts. The NEA aggregates data on things like rainfall and humidity levels in various parts of Singapore in order to determine the risk of mosquito breeding.

Key Takeaways

Neglected diseases have major healthcare and economic implications in middle-income countries, especially amid intensifying urbanisation, climate change and international travel. Policy-makers have historically tended to focus on crisis responses to disease outbreaks, but this short-term focus can be costly in the long term.

Experts highlight the importance of sustained disease control efforts and call for a more long-term, integrated policy response that goes well beyond healthcare. This can include the following policy responses:

• Eradication of the animals that spread diseases;

• Harnessing big data and technology for better integrated disease surveillance and outbreak preparedness;

• Immunisation and vaccination campaigns to prevent the spread of epidemics;

• An alliance-based approach that leverages "partnership capital" and enhanced collaboration between key stakeholders;

• Smart city design to strengthen service delivery by making health investments that align with urban-planning goals.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited (EIU) or any other member of The Economist Group. The Economist Group (including the EIU) cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this article or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in the article.