Respondents in the Middle East and Africa (MEA) are the strongest believers in a cashless society. According to a retail banking survey conducted by The Economist Intelligence Unit, a full 59% of MEA-based respondents think cash will dip below 5% of retail transactions in the next five years compared with a global average of 48%. But a big digital switch need not mean the end of face-to-face banking. Respondents in MEA are the least likely to believe that customers will forgo human contact (42% vs a 51% global average) even if digital services are free or low-cost.

MEA banks may have a lot of work to complete in a very short time. The region trails behind in both account and card ownership, typically the first steps towards a digital service for many customers. Less than half of all MEA-based adults had accounts with financial institutions in 2017, with even fewer using debit or credit cards. Just one in twenty Algerians claimed to have used a card for any payment in the previous year.1

Even where customers have accounts and cards, there are huge regional variations between the number of digital payments made. In richer countries such as Kuwait or the United Arab Emirates (UAE) the majority of adults had made an online payment in the previous 12 months. This figure drops to less than one in four in Egypt and other North African countries where mobile money operators (MMOs) have far less reach than elsewhere across the African continent.

Inclusive banking

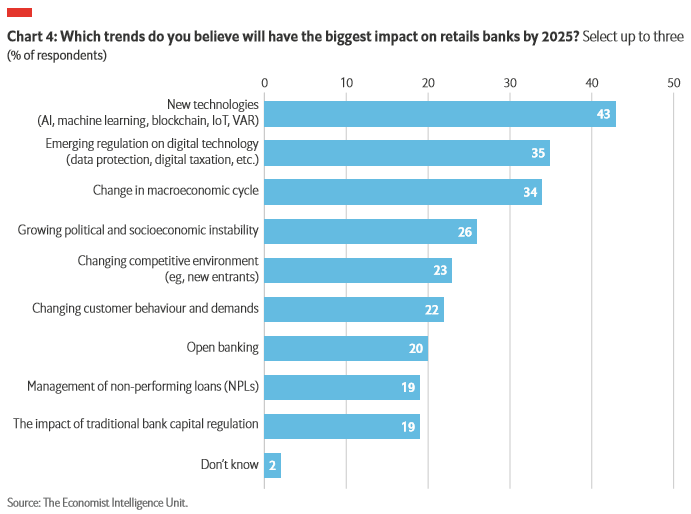

Despite these limitations, it appears that banks have made fairly good progress towards moving existing customers to digital channels. This is particularly notable given that client migration is not considered an immediate priority (cited by just 23% of respondents as a main goal for 2020). Yet MEA banks are highly conscious that financial exclusion and delaying digitisation are genuine threats to their business models. For the 2020 timeframe, changing customer demands are considered the highest-impact trend as cited by 35% of respondents. By 2025, 43% think new technologies will be the most impactful development. Both trends may prove harmful if banks cannot swiftly widen their reach.

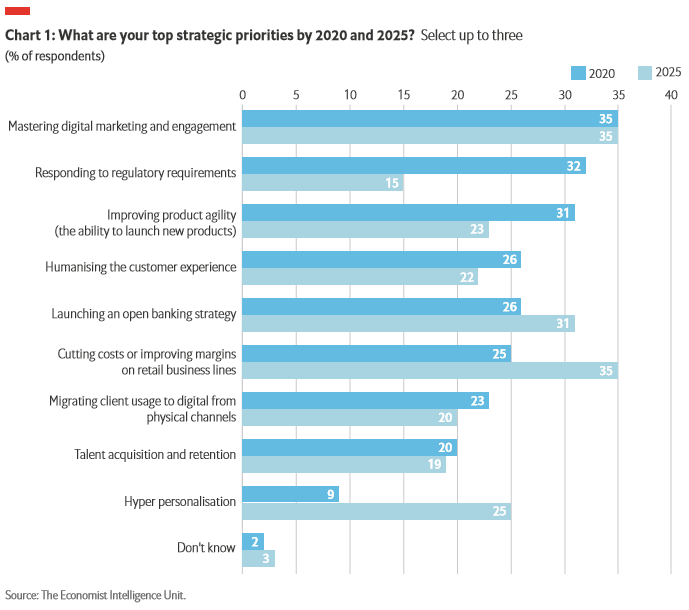

To respond to the threat from payment players, big tech, remittance outfits, new retail and small to medium-sized enterprise (SME) lending firms, banks need to boost their product agility. This is a strategic priority for 31% of respondents by 2020. The need to sharpen digital marketing skills to bring excluded customers into the banking sphere is widely recognised, with 35% prioritising it in 2020, and another 35% expecting it to become a priority by 2025. Responding to regulatory requirements is also an immediate concern for this year, as cited by 32% of survey respondents. Spending heavily on tech must also generate a return: cost-cutting and margin pressures are likely to weigh heavily on executive decisions over the next five years according to 35% of interviewees.

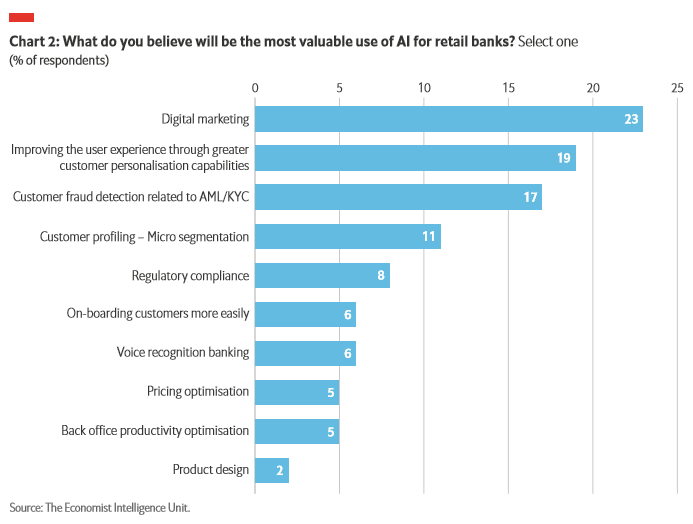

When it comes to technology deployment, expectations of AI are similar to global assumptions with a focus on improvement of user experience (19%) and customer fraud detection (17%). But there is one exception: MEA respondents are far more likely to cite digital marketing as the most valuable use for AI (23% vs 13% globally). That may be a sign that targeting and attracting the unbanked and underbanked into the digital ecosystem is critical.

Marketing, analytics and customisation place new pressures on IT strategies and spending. With companies focusing on drawing in new customers, scalable cloud banking (a priority area for 40% of respondents) is taking up a bigger share of digital budgets than cybersecurity (34%) across MEA, and is a bigger spending priority than in other regions (35% global average).

Identifying the opportunity

The Middle East should be particularly well-placed to make the transition to digital inclusion. Populations are young and smartphone use is predicted to hit 74% by 20252—in some countries there are already more smartphones than people.

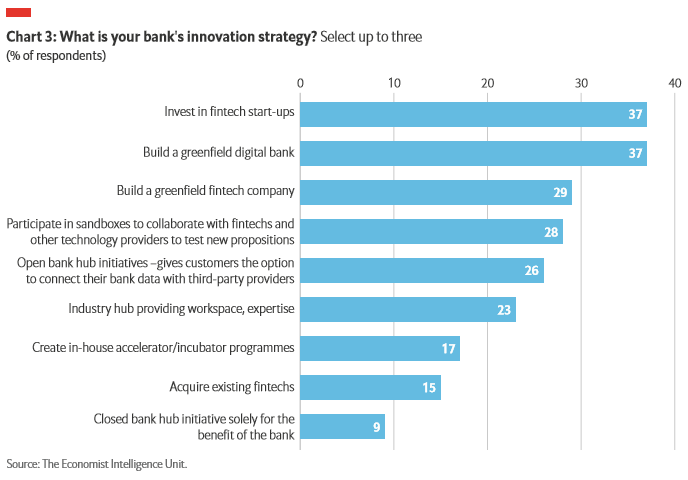

The affordability of smartphones is a key driver in the new development of mobile-only and mobile-first greenfield banks, the top innovation strategy chosen by 37% of MEA-based

respondents alongside investing in fintech start-ups (37%). Nearly one in three respondents (29%) is innovating by building a greenfield fintech firm, also the top pick on a global level (36%).

Governments also realise that the digital economy can encourage inclusion, improve productivity and, in the Middle East, help diversify away from a heavy dependence on the oil industry. Middle Eastern governments also have the resources and regulatory tools to make it a strategic priority for the private and public sectors. Across the region, countries have looked to the likes of India’s mass digital ID programme, Aadhaar, for inspiration. That is good news: 40% of MEA respondents say difficulty establishing digital identities is their biggest regulatory concern.

In the UAE national digital IDs are now operational, allowing banks and their tech providers to explore and implement paperless “know your customer” authentication (e-KYC) to improve and speed up the on-boarding process for new customers. Initiatives such as “smart Dubai” aim to rid the city of paperwork entirely and provide the data on which to build better services for residents.

As governments embrace digital agendas, local banks have an opportunity to catch up with or even overtake their peers in other regions. With financial centres in Abu Dhabi, Bahrain, Dubai and Riyadh battling for dominance, cross-border banks are seeking to consolidate their market shares while smaller players see an opportunity to export their technological prowess to new markets.

The government and central bank of Bahrain have set ambitious targets and timetables to digitise Bahraini life and the local banking sector. Banks are racing to comply, updating their systems and work practices as new regulations take effect.

Bahrain was also first in the region to launch a national fintech hub, dubbed “FinTech Bay”, to develop a local ecosystem and encourage collaboration. It has modernised its venture capital and angel funding vehicle structures in order to attract the capital necessary for SMEs to successfully scale up. And bankruptcy laws have been liberalised so that innovators are not personally punished if their ventures fail.

African leap

The situation in Africa splits roughly between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of the uptake of MMOs and the response by incumbent banks. North Africa remains fairly cashdependent and is mainly behind the curve when it comes to fintech adoption. That is changing, however, as governments and investors tap the opportunities brought by digitalisation. Egypt recently mandated digital inclusion and cashless payments for public services, prompting local banks including Egypt Post and Banque du Caire to update legacy systems and adopt digital or omni-channel distribution strategies.

In other markets, MMOs have already had a big impact on how daily life operates. In Kenya, and now other countries, banks failing to gain traction with their own platforms are now using MMOs as a conduit to sell other banking products. The Commercial Bank of Africa created a mobile bank account called M-Shwari in partnership with Kenya’s Safaricom (the provider of mobile wallet M-Pesa), through which users can access micro loans and savings. Such services could be the gateway needed by unbanked Africans to access formal banking.

Banks are also pushing for a level regulatory playing field. Zimbabwe is one of the latest countries in which banks are lobbying hard for stricter regulation of mobile money operators3. They may have a strong argument that MMOs are effectively deposit-takers given their vast networks of physical stalls or merchants that accept cash-in or allow cash-outs from their systems. If that is the case, MMOs can expect more consumer protection obligations and possibly even capital requirements to ensure they do not pose an outside risk to financial stability. How that might affect their low-cost business models remains to be seen.

[1]The Global Findex Database, 2017, The World Bank

[2] The Mobile Economy Middle East and North Africa 2018, GSMA https://www.gsma.com/r/mobileeconomy/mena/

[3] https://www.herald.co.zw/banks-money-transfer-agencies-clash/